Adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system is made of specialized cells and processes which kill pathogens or prevent their attack.

The adaptive immune system is switched on by the evolutionarily older innate immune system.[1] This older system is non-specific, whereas the adaptive system is tailored to specific targets.

Whereas the innate immune system is found in all metazoa, the adaptive system is only found in vertebrates. It is thought to have arisen in the first jawed vertebrates.[1][2]

The adaptive immune response gives the vertebrate immune system the ability to recognize and remember specific pathogens. The system mounts stronger attacks each time a particular pathogen is encountered. It is adaptive immunity because the body's immune system prepares itself for future challenges.

Layered defence

[change | change source]The immune system protects organisms from infection with layered defences. In simple terms, physical barriers prevent pathogens such as bacteria and viruses from entering the organism.

If a pathogen breaches these barriers, the innate immune system provides an immediate, but non-specific response. Innate immune systems are found in all plants and animals.[3]

If pathogens successfully evade the innate response, vertebrates possess a third layer of protection, the adaptive immune system, which is activated by the innate response. Here, the immune system adapts its response during an infection to improve its recognition of the pathogen.

After the pathogen has been killed, the offspring of B and T cells continue. They are ready for a faster response next time. This is a kind of 'immunological memory'. These cells allow the adaptive immune system to mount faster and stronger attacks each time this pathogen is encountered.[4]

| Innate immune system | Adaptive immune system |

|---|---|

| Response is non-specific | Pathogen and antigen specific response |

| Exposure leads to immediate maximal response | Lag time between exposure and maximal response |

| Cell-mediated and humoral components | Cell-mediated (T lymphocytes) and humoral (antibody) components |

| No immunological memory | Exposure leads to immunological memory |

| Found in nearly all forms of life | Found only in jawed vertebrates |

Both innate and adaptive immunity depend on the ability of the immune system to distinguish between self and non-self molecules. In immunology, self molecules are those components of an organism's body that can be distinguished from foreign substances by the immune system.[5] Conversely, non-self molecules are those recognized as foreign molecules. One class of non-self molecules are called antigens (short for antibody generators) and are defined as substances that bind to specific immune receptors and elicit an immune response.[6]

Functions

[change | change source]In animals with backbones, the adaptive immune system is activated when a germ manages to sneak past the body's first line of defense (the innate immune system) and produces a certain amount of a particular signal.[7]

The main jobs of the adaptive immune system are:

- to recognize specific invaders that do not belong in the body,

- to make a customized response to fight them, and

- to remember how to fight them if they ever come back.

The adaptive immune system recognizes these invaders when special cells called macrophages and dendritic cells collect them and present them to other cells called T cells, which recognize the invaders and help fight them.

| Naturally acquired | Artificially acquired |

|---|---|

| Active- Antigen enters the body naturally | Active- Antigens are introduced in vaccines. |

| Passive-Antibodies pass from mother to fetus via placenta or infant via the mother's milk. | Passive- Preformed antibodies in immune serum are introduced by injection. |

Components of the adaptive immune system

[change | change source]B cells

[change | change source]B cells are type of white blood cell that responsible for producing antibodies, which are proteins that can recognize and bind to specific antigens, such as bacteria or viruses. B cells are produced in the bone marrow and circulated in the lymph nodes, spleen, and other lymphoid organs.

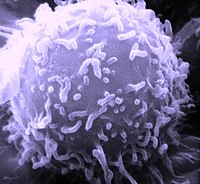

T cells

[change | change source]T cells are another type of white blood cell that are a key component of the adaptive immune system. Unlike B cells, which recognize antigens in their native form, T cells recognize antifens that are presented to the by other cells in the body. This is because T cells express a unique receptor called the T cell receptor (TCR), which can only recognize antigen fragments that are displayed on the surface of other cells.

Diseases of the adaptive immune system

[change | change source]Autoimmune disease

[change | change source]Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system mistakenly targets and attacks the body's own tissues, mistaking them for foreign antigens. This can lead to a wide variety of conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and type I diabetes.

Immunodeficiency disorders

[change | change source]Immunodeficiency disorders occur when the immune system is unable to mount an effective responses to infections, leaving the body vulnerable to a wide range of pathogens. Examples of immunodeficiency disorders include primary immunodeficiency diseases, such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), as well as acquired immunodeficiency diseases, such as HIV/AIDS.

Hypersensitivity reactions

[change | change source]Hypersensitivity reactions occur when the immune system overreacts to harmless substances, such as pollen, food, or medications. This can lead to a range of symtoms, from mild rashes and itching to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

Related pages

[change | change source]

For the adaptive immune system used by bacteria against viruses, see CRISPR.

References

[change | change source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Janeway C.A. 2001. Evolution of the immune system. In Immunobiology ed Janeway et al. 5th ed, 597–607. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7

- ↑ Hirano, Masayuki; Das, Sabyasachi; Guo, Peng; Cooper, Max D. (2011-01-01), Alt, Frederick W. (ed.), The Evolution of Adaptive Immunity in Vertebrates, Advances in Immunology, vol. 109, Academic Press, pp. 125–157, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-387664-5.00004-2, ISBN 9780123876645, PMID 21569914, retrieved 2019-12-03

- ↑ Litman GW, Cannon JP, Dishaw LJ (2005). "Reconstructing immune phylogeny: new perspectives". Nature Reviews: Immunology. 5 (11): 866–79. doi:10.1038/nri1712. PMC 3683834. PMID 16261174.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mayer, Gene (2006). "Immunology chapter 1: Innate (non-specific) immunity". Microbiology and Immunology on-line textbook. USC School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2011-08-23. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ↑ Smith A.D. (ed) 1997. Oxford dictionary of biochemistry and molecular biology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854768-6

- ↑ Alberts, Bruce et al 2002. Molecular biology of the cell; 4th ed, New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3 Archived 17 August 2006 at WebCite

- ↑ Janeway C.A et al 2001. Immunobiology. 5th ed, New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7