A Christmas Carol

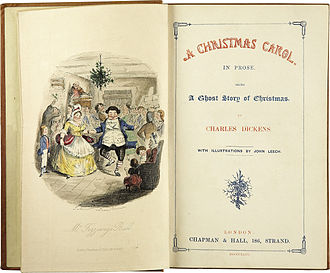

A Christmas Carol is a novella by the British writer Charles Dickens. It was first published on 19 December 1843 by Chapman & Hall in London. John Leech made the illustrations. The first edition was a beautiful and expensive book. It was sold out by Christmas Eve, but Dickens never made the money he expected on the tale due to the book's high production costs.

When Dickens wrote the novella, the British were longing for the traditional merry Old English Christmas. Christmas customs of the past were being revived. New Christmas customs such as the Christmas tree and the greeting card were making their first appearances. Old carols were being sung. The novella has been credited with restoring the festive spirit of Christmas after a period of Puritan sobriety and solemnity. [source?]

The story is about a Christmas-hating miser named Ebenezer Scrooge. On Christmas Eve, he is visited by four ghosts who transform him into a kind and generous man. The story has a strong moral messages about greed and poverty. It is usually read at Christmas time and has been adapted to theatre, movies, radio, and television many times.

Background

[change | change source]Charles Dickens was from a middle-class family. The family got into financial difficulty, because Charles' father, John Dickens, was bad at dealing with money. In 1824, John Dickens was put in prison, because of the debt he had. Charles had to pawn his collection of books, and leave shool to work at a factory. He was twelve years old at the time. The factory where he worked produced shoe polish. It was dirty and there were many rats. The change gave him what his biographer, Michael Slater, describes as a "deep personal and social outrage", which heavily influenced his writing and outlook.[1][2]

By the end of 1842, Dickens was a well-established author with six major works[n 1] as well as many short stories, novellas and other pieces.[3] On 31 December that year he started publishing his novel Martin Chuzzlewit as a monthly serial. There weere 20 parts, the last one was published on 30 June 1844.[4] It was his favourite work, but sales were low and he faced temporary financial difficulties.[4]

Celebrating the Christmas season had become more popular through the Victorian era.[5] The Christmas tree was introduced in Britain during the 18th century, and Queen Victoria and Prince Albert popularised its use.[6] In the early 19th century people had become more interested in Christmas carols again. Their popularity of these stories had declined over the previous hundred years. The publication of Davies Gilbert's 1823 work Some Ancient Christmas Carols, With the Tunes to Which They Were Formerly Sung in the West of England and William Sandys's 1833 collection Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern led christmas carols becoming more popular in Britain.[7]

Dickens had an interest in Christmas. His first story on the subject was "Christmas Festivities". It was first published in Bell's Weekly Messenger in 1835. The story was then published as "A Christmas Dinner" in Sketches by Boz (1836).[8] "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton", another Christmas story, appeared in the 1836 novel The Pickwick Papers. In the episode, a Mr Wardle describes a misanthropic (people hater) sexton, Gabriel Grub. Grub changes his ways at Christmas after being visited by goblins who show him the past and future.[9] Slater considers that "the main elements of the Carol are present in the story", but not yet in a firm form.[10] The story is followed by a passage about Christmas in Dickens's editorial Master Humphrey's Clock.[10] The professor of English literature Paul Davis writes that although the "Goblins" story appears to be a prototype of A Christmas Carol, all Dickens's earlier writings about Christmas influenced the story.[11]

By mid-1843 Dickens started to suffer from financial problems. Sales of Martin Chuzzlewit were falling off, and his wife, Catherine, was pregnant with their fifth child. Matters worsened when Chapman & Hall, his publishers, threatened to reduce his monthly income by GB£50 (equivalent to £4,945 in 2019) if sales dropped further.[12] He started A Christmas Carol in October 1843.[13] Michael Slater, Dickens's biographer, describes the book as being "written at white heat"; it was completed in six weeks, the final pages were written in early December.[14] He built much of the work in his head while taking night-time walks of 15 to 20 miles (24 to 32 km) around London.[15] Dickens's sister-in-law wrote how he "wept, and laughed, and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner, in composition".[16] Slater says that A Christmas Carol was

intended to open its readers' hearts towards those struggling to survive on the lower rungs of the economic ladder and to encourage practical benevolence, but also to warn of the terrible danger to society created by the toleration of widespread ignorance and actual want among the poor.[17]

George Cruikshank, the illustrator who had earlier worked with Dickens on Sketches by Boz (1836) and Oliver Twist (1838), introduced him to the caricaturist John Leech. By 24 October Dickens invited Leech to work on A Christmas Carol, and four hand-coloured etchings and four black-and-white wood engravings by the artist accompanied the text.[18] Dickens's hand-written manuscript of the story does not include the sentence in the penultimate paragraph "... and to Tiny Tim, who did not die"; this was added later, during the printing process.[19][n 2]

Publication

[change | change source]

Martin Chuzzlewit did not sell well, and Dickens had some disagreements with his publisher Chapman and Hall.[20] For this reason, Dickens said he would pay for the publishing himself, in exchange for getting a part of the profits.[21]

There were also some problems with the production. The first printing was meant to have festive green endpapers, but they came out a dull olive colour. Dickens' publisher Chapman and Hall replaced these with yellow endpapers and reworked the title page in harmonising red and blue shades.[22] The final product was bound in red cloth with gilt-edged pages. It was completed only two days before the publication date of 19 December 1843.[23] Following publication, Dickens arranged for the manuscript to be bound in red Morocco leather and presented as a gift to his solicitor, Thomas Mitton.[24][n 3]

The first edition was priced at five shillings (equal to £25 in 2025 pounds).[25] Its 6,000 copies sold out by Christmas Eve, five days later. Chapman and Hall issued second and third editions before the new year, and the book continued to sell well into 1844.[27] By the end of 1844 eleven more editions had been released.[28] Since its initial publication the book has been issued in numerous hardback and paperback editions, translated into several languages and has never been out of print.[29] It was Dickens's most popular book in the United States, and sold over two million copies in the hundred years following its first publication there.[30]

The high production costs upon which Dickens insisted led to reduced profits, and the first edition brought him only GB£230 (equivalent to £22,746 in 2019)[25] rather than the GB£1,000 (equivalent to £98,897 in 2019)[25] he expected.[31] A year later, the profits were only GB£744, and Dickens was deeply disappointed.[20][n 4]

Plot

[change | change source]

Ebenezer Scrooge is a Christmas-hating old miser and businessman. One Christmas Eve, Scrooge declines an invitation to his nephew's house for Christmas dinner, telling his nephew that Christmas is "Humbug". He then refuses to give a donation to two men who are collecting for charity.

Later that evening, the ghost of his dead business partner Jacob Marley, a man whose greed and selfishness have doomed him to eternal hellfire, visits him. He tells Scrooge that he must change his ways or that hellfire will be his fate. Marley warns him that during the night three more ghosts will visit him. These will show him where he went wrong in his life, and how to be a better person in the future.

The first ghost is the Ghost of Christmas Past. This ghost shows him his unhappy childhood and how he did not get married.

The second ghost is the Ghost of Christmas Present. This ghost shows him things which are happening now, such as how his clerk, Bob Cratchit, is having a nice Christmas despite not having much money. He also shows him Bob's youngest son, called Tiny Tim, who is crippled. Later, the ghost shows him how his nephew is having a good Christmas, and how Scrooge is missing out.

The third ghost is the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. This ghost shows Scrooge what Christmas will be like in the future if he does not change. First, people are shown celebrating a man's death and robbing his house. The ghost also shows him that Tiny Tim has died. Scrooge is then shown his own grave, and realizes that the celebrations were for his death.

On Christmas morning, Scrooge wakes up and realizes that he has to change. He decides to celebrate Christmas, and help Tiny Tim get well. He sends the Cratchit family a prize turkey for their holiday dinner. Through the ghosts' help, Scrooge becomes a better man.

Legacy

[change | change source]The book made popular the phrase "Merry Christmas" as well as the name "Scrooge" and the phrase "Bah! Humbug". The book spurred charitable giving in the years following its first publication. Its lasting legacy is returning to Christmas the merriment and festivity the day lost after a period of Puritan sobriety.

Notes

[change | change source]- ↑ These were Sketches by Boz (1836); The Pickwick Papers (1836); Nicholas Nickleby (1837); Oliver Twist (1838); The Old Curiosity Shop (1841); and Barnaby Rudge (1841).[3]

- ↑ The addition of the line has proved contentious to some.[19] One writer in The Dickensian – the journal of the Dickens Fellowship wrote in 1933 that "the fate of Tiny Tim should be a matter of dignified reticence ... Dickens was carried away by exuberance, and momentarily forgot good taste".[19]

- ↑ In 1875 Mitton sold the manuscript to the bookseller Francis Harvey – reportedly for £50 (equal to £4,700 in 2025 pounds) –[25] who sold it to the autograph collector, Henry George Churchill, in 1882; in turn Churchill sold the manuscript to Bennett, a Birmingham bookseller. Bennett sold it for £200 to Robson and Kerslake of London, which sold it to Dickens collector Stuart M. Samuel for £300. It was purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan for an undisclosed sum and is now held by the Morgan Library & Museum, New York.[26]

- ↑ Dickens's biographer, Claire Tomalin, puts the first edition profits at £137, and those by the end of 1844 at £726.[30]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ Ackroyd, Peter (1990). Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-1-85619-000-8.

- ↑ Slater, Michael (2011). "Dickens, Charles John Huffam". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7599.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diedrick 1987, p. 80.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ackroyd, Peter (1990). Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-85619-000-8.

- ↑ Callow 2009, p. 27.

- ↑ Lalumia 2001; Sutherland, British Library.

- ↑ Rowell 1993; Studwell & Jones 1998, pp. 8, 10; Callow 2009, p. 128.

- ↑ Callow 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Kelly 2003, pp. 19–20; Slater 2003, p. xvi.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Slater 2003, p. xvi.

- ↑ Davis 1990a, p. 25.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xvi; Callow 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Rowell 1993.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xix; Slater 2011 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSlater2011 (help).

- ↑ Tomalin 2011, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Davis 1990a, p. 7.

- ↑ Slater 2011. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSlater2011 (help)

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xix; Tomalin 2011, p. 148.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Davis 1990a, p. 133.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Kelly 2003, p. 17.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xix.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xxxi; Varese 2009.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xix; Varese 2009; Sutherland, British Library.

- ↑ Provenance, The Morgan Library & Museum.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 UK CPI inflation.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xxx; Provenance, The Morgan Library & Museum.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, pp. xix–xx; Standiford 2008, p. 132.

- ↑ Jackson 1999, p. 6.

- ↑ Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. viii; A Christmas Carol, WorldCat.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Tomalin 2011, p. 150.

- ↑ Kelly 2003, p. 17; Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, pp. xx, xvii.

Sources

[change | change source]Books

[change | change source]- Ackroyd, Peter (1990). Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 978-1-85619-000-8.

- Billen, Andrew (2005). Charles Dickens: The Man Who Invented Christmas. London: Short Books. ISBN 978-1-904977-18-6.

- Callow, Simon (2009). Dickens' Christmas: A Victorian Celebration. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3031-6.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1840). Chartism. London: J. Fraser. OCLC 247585901.

- Chesterton, G. K. (1989). The Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton: Chesterton on Dickens. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-0-89870-258-3.

- Cochrane, Robertson (1996). Wordplay: origins, meanings, and usage of the English language. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7752-3.

- Davis, Paul (1990a). The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04664-9.

- Deacy, Christopher (2016). Christmas as Religion: Rethinking Santa, the Secular, and the Sacred. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-106955-0.

- DeVito, Carlo (2014). Inventing Scrooge (Kindle ed.). Kennebunkport, ME: Cider Mill Press. ISBN 978-1-60433-555-2.

- Dickens, Charles (1843). A Christmas Carol. London: Chapman and Hall. OCLC 181675592.

- Diedrick, James (1987). "Charles Dickens". In Thesing, William (ed.). Dictionary of Literary Biography: Victorian Prose Writers before 1867. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale. ISBN 978-0-8103-1733-8.

- Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert (2006). "Introduction". In Dickens, Charles (ed.). A Christmas Carol and other Christmas Books. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–xxix. ISBN 978-0-19-920474-8.

- Forbes, Bruce David (2008). Christmas: A Candid History. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-520-25802-0.

- Garry, Jane; El Shamy, Hasan (2005). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-2953-1.

- Glancy, Ruth F. (1985). Dickens' Christmas Books, Christmas Stories, and Other Short Fiction. Michigan: Garland. ISBN 978-0-8240-8988-7.

- Hammond, R. A. (1871). The Life and Writings of Charles Dickens: A Memorial Volume. Toronto: Maclear & Company.

- Harrison, Mary-Catherine (2008). Sentimental Realism: Poverty and the Ethics of Empathy, 1832–1867 (Thesis). Ann Arbor, MI. ISBN 978-0-549-51095-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Howells, William Dean (1910). My literary passions, criticism and fiction. New York and London: Harper & Brother. p. 2986994. ISBN 978-1-77667-633-0.

- Hutton, Ronald (1996). Stations of the Sun: The Ritual Year in England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285448-3.

- Jordan, Christine (2015). Secret Gloucester. Stroud, Glos: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-4689-3.

- Jordan, John O. (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66964-1.

- Kelly, Richard Michael (2003). "Introduction". In Dickens, Charles (ed.). A Christmas Carol. Ontario: Broadway Press. pp. 9–30. ISBN 978-1-55111-476-7.

- Ledger, Sally (2007). Dickens and the Popular Radical Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84577-9.

- Moore, Grace (2011). Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol. St Kilda, VIC: Insight Publications. ISBN 978-1-921411-91-5.

- Pykett, Lyn (2017). Charles Dickens. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4039-1919-9.

- Restad, Penne L. (1996). Christmas in America: a History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510980-1.

- Sillence, Rebecca (2015). Gloucester History Tour. Stroud, Glos: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-4859-0.

- Slater, Michael (2003). "Introduction". In Dickens, Charles (ed.). A Christmas Carol and other Christmas Writings. London: Penguin Books. pp. xi–xxviii. ISBN 978-0-14-043905-2.

- Slater, Michael (2009). Charles Dickens. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16552-4.

- Standiford, Les (2008). The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits. New York: Crown. ISBN 978-0-307-40578-4.

- Studwell, William Emmett; Jones, Dorothy E. (1998). Publishing Glad Tidings: Essays on Christmas Music. Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Press. ISBN 978-0-7890-0398-0.

- Tomalin, Claire (2011). Charles Dickens: A Life. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-91767-9.

- Welch, Bob (2015). 52 Little Lessons from a Christmas Carol. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-4002-0675-9.

Online resources

[change | change source]- "A Christmas Carol". The Radio Times (12): 23. 14 December 1923.

- "A Christmas Carol". WorldCat. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Ansari, Samina (7 May 2020). "How the BMI gave Charles Dickens a new career". The Birmingham & Midland Institute. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- Davidson, Ewan. "Scrooge, or, Marley's Ghost (1901)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Elwell, Frank W. (2 November 2001). "Reclaiming Malthus". Rogers State University. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017.

- Lalumia, Christine (12 December 2001). "Scrooge and Albert". History Today.

- Lee, Imogen. "Ragged Schools". British Library. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Martin, Katherine Connor (19 December 2011). "merry, adj". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.(subscription required)

- "Provenance". The Morgan Library & Museum. 20 November 2013.

- Rowell, Geoffrey (12 December 1993). "Dickens and the Construction of Christmas". History Today.

- "Scrooge, n". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 16 January 2017.(subscription required)

- Sutherland, John (15 May 2014). "The Origins of A Christmas Carol". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Varese, Jon Michael (22 December 2009). "Why A Christmas Carol was a flop for Dickens". The Guardian.

- UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Dickens Visits Birmingham". Birmingham Conservation Trust. 19 December 2012.

Newspapers, journals and magazines

[change | change source]- Alleyne, Richard (24 December 2007). "Real Scrooge 'was Dutch gravedigger'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- "Charles Dickens; Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition". The New York Times. 19 December 1863.

- Chorley, H. F. (23 December 1843). "A Christmas Carol". The Athenaeum (843): 1127–1128.

- "Christmas Carol". The New Monthly Magazine. 70 (277): 148–149. January 1844.

- Davis, Paul (Winter 1990b). "Literary History: Retelling A Christmas Carol: Text and Culture-Text". The American Scholar. 59 (1): 109–15. JSTOR 41211762.

- Gordon, Alexander; McConnell, Anita (2008). "Elwes [formerly Meggott], John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8776. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hood, Thomas (January 1844). "A Christmas Carol". Hood's Magazine. 1 (1): 68–75.

- Jackson, Crispin (December 1999). "Charles Dickens, Christmas Books and Stories". The Book and Magazine Collector (189).

- Jaffe, Audrey (March 1994). "Spectacular Sympathy: Visuality and Ideology in Dickens's A Christmas Carol". PMLA. 109 (2): 254–265. doi:10.2307/463120. JSTOR 463120. S2CID 163598705.

- "Literature". The Illustrated London News. No. 86. 23 December 1843.

- Martin, Theodore (February 1844). "Bon Gaultier and his Friends". Tait's Edinburgh Magazine. 11 (2): 119–131.

- "Notice of Books". The Christian Remembrancer. 7 (37): 113–121. January 1844.

- Pelling, Rowan (7 February 2014). "Mr Punch is still knocking them dead after 350 years". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Sable, Martin H. (Autumn 1986). "The Day of Atonement in Charles Dickens' 'A Christmas Carol'". Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought. 22 (3): 66–76. JSTOR 23260495.

- Senior, Nassau William (June 1844). "Spirit of the Age". The Westminster Review. 41 (81): 176–192.

- Slater, Michael (2011). "Dickens, Charles John Huffam". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7599.

- Thackeray, William Makepeace (February 1844). "A Box of Novels". Fraser's Magazine. 29 (170): 153–169.

Other websites

[change | change source] Works related to A Christmas Carol at Wikisource

Works related to A Christmas Carol at Wikisource- A Christmas Carol at Project Gutenberg