Conservative Revolution

The English used in this article or section may not be easy for everybody to understand. |

This page or section needs to be cleaned up. (February 2025) |

This article may be too long to read and move around comfortably. (February 2025) |

The Conservative Revolution (German: Konservative Revolution), also called the German neoconservative movement[1] or new nationalism,[2] was a political movement in Germany and Austria from 1918 to 1933, between World War I and the rise of the Nazis. It was a national-conservative and ultraconservative movement that opposed modern ideas and wanted a different future for Germany.

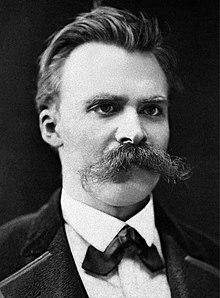

The people in this movement, called conservative revolutionaries, rejected traditional Christian conservatism, democracy, and equality. They felt lost in the modern world and looked to older ideas from the 19th century. These included Friedrich Nietzsche’s dislike of Christian values and democracy, the anti-modern ideas of German Romanticism, the nationalist beliefs of the Völkisch movement, and the strong military traditions of Prussia. Many were also influenced by their experiences of war and comradeship during World War I.

The Conservative Revolution had a complicated connection with Nazism. Some historians see it as a form of early fascism, though it was not exactly the same as Nazism. Unlike the Nazis, it did not always focus on race, but it shared anti-democratic ideas that helped prepare German society for Nazi rule. When Hitler took power in 1933, the movement lost its influence. One of its key thinkers, Edgar Jung, was killed by the Nazis in 1934. Some members later opposed parts of Nazi rule, except for figures like Carl Schmitt.

Since the 1960s and 1970s, the Conservative Revolution has influenced right-wing political movements in Europe, especially in France and Germany. It has also helped shape the modern European Identitarian movement.

Name and meaning

[change | change source]Although conservative writers from the Weimar Republic, like Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Edgar Jung, called their political movement the "Conservative Revolution,"[3] the term became popular again after Armin Mohler's doctoral thesis in 1949.[4] Mohler's post-war ideas about the "Conservative Revolution" have faced a lot of criticism, but many scholars now accept the concept of a "neo-conservative"[5] or "new nationalist" movement that was active during the Weimar years (1918–1933).[6] This period sometimes includes the 1890s to 1910s and is seen as different from the 19th-century "old nationalism."

Some modern historians find the term "Conservative Revolution" confusing and suggest using "neo-conservative" instead. Sociologist Stefan Breuer suggested the term "new nationalism" to describe a dynamic and inclusive cultural movement that was distinct from the previous century's nationalism, which mainly aimed to maintain German institutions and their global influence.[7] Despite seeming contradictions, Moeller van den Bruck's writings justify the connection between "Conservative" and "Revolution" by defining the movement as a desire to keep enduring values while also adapting ideals and institutions to address the challenges of modern life.[8]

Historian Louis Dupeux, who studies the Conservative Revolution, viewed the movement as a thoughtful effort with its own clear logic. This effort aimed for 'intellectual power,' using modern techniques and ideas to promote conservative and revolutionary beliefs against liberalism, equality, and traditional conservatism. This shift in view, compared to 19th-century conservatism, is called 'affirmation' by Dupeux: Conservative Revolutionaries embraced their time as long as they could revive what they saw as 'eternal values' in modern society. Dupeux acknowledged that the Conservative Revolution was more of a counter-culture than a real philosophical idea, relying on 'feelings, images, and myths' rather than scientific reasoning. He also recognized the need to identify different views within its various beliefs.[9]

- Conservative Revolutionaries are, indeed, as politically reactive as their predecessors, but they display optimism—or at least a strong will—towards the modern world. They no longer fear the masses or technology. This change in attitude has led to significant effects—replacing past regrets with youthful energy—and has sparked broad political and cultural actions.— Louis Dupeux, 1994

Political scientist Tamir Bar-On describes the Conservative Revolution as a mix of extreme German nationalism, support for close-knit communities, modern technology, and a changed version of socialism. It saw workers and soldiers as examples for a new authoritarian state, moving beyond the perceived decline caused by liberalism, socialism, and traditional conservatism.[10]

Origin and development

[change | change source]The Conservative Revolution is part of a bigger movement against the French Revolution of 1789, shaped by early 19th-century Romanticism's dislike for modern ideas and reason. This is seen especially in Germany and Prussia, where there was a strong military, authoritarian nationalism that opposed liberalism, socialism, democracy, and international cooperation.[3] Historian Fritz Stern described these people as confused thinkers caught in deep 'cultural despair'; they felt lost in a world controlled by what they considered 'middle-class reasoning and science'. Stern notes that their anger at modernity led them to mistakenly believe that all these modern problems could be solved by a 'Conservative Revolution'.[11]

Terms like Konservative Kraft ('conservative power') and schöpferische Restauration ('creative restoration') became common in German-speaking Europe from the 1900s to the 1920s. The Konservative Revolution ('Conservative Revolution') became a recognized idea in the Weimar Republic (1918–1933) thanks to writers like Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Hermann Rauschning, Edgar Jung, and Oswald Spengler.[13]

Alfred Hugenberg started the Alldeutscher Verband ("Pan-German League") in 1891 and the Jugendbewegung ("youth movement") in 1896. These helped the rise of the Conservative Revolution in the years that followed.[14] Moeller van den Bruck was the main leader of this movement until he took his own life on May 30, 1925.[15] His ideas were first shared through the Juniklub he created on June 28, 1919, the day the Treaty of Versailles was signed.[14]

Conservative Revolutionaries often called German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche their mentor and saw him as the main thinker behind their movement.[16] Even though Nietzsche's ideas are often misunderstood or misused by these thinkers,[17] they kept his dislike for Christian morals, democracy, modern ways, and equality as key parts of their beliefs. Historian Roger Woods says that Conservative Revolutionaries created a version of Nietzsche who supported bold actions, strong self-assertion, conflict over peace, and trusting instincts more than reason.[18]

Many thinkers in the movement were born in the late 1800s and saw WWI as a key event that shaped their political ideas.[19] Their harsh experiences on the front line made most of them look for meaning in what they went through during the war.[20] Ernst Jünger is a key figure in the Conservative Revolution, which aimed to maintain military values in peacetime and believed that the brotherhood among soldiers showed the real spirit of German socialism.[21]

Main thinkers

[change | change source]As noted by Armin Mohler and other sources, key figures in the Conservative Revolution were:

Ideology

[change | change source]The German Conservative Revolution, as explained by historian Roger Woods' idea of the "conservative dilemma,"[48] can be characterized by its opposition to:

- the traditional conservative values of the German Empire (1871–1918), which include Christian equality; the push to restore the old Wilhelmine empire along its past political and cultural lines;[3]

- the political system and business culture of the Weimar Republic; and democracy in general, because the national community should go beyond the usual left-right divide;[49]

- the class ideas of socialism, defending an anti-Marxist "socialist revisionism,"[10] which Oswald Spengler called the "socialism of the blood" and was inspired by the brotherhood seen in World War I.[3]

New nationalism and morality

[change | change source]

Oswald Spengler, who wrote The Decline of the West, represented a cultural pessimism that partly defined the Conservative Revolution. Conservative Revolutionaries believed their nationalism was different from earlier forms of German nationalism or conservatism.[13] They criticized traditional Wilhelmine conservatives for being backward and not fully grasping new ideas of the modern era, like technology, cities, and the working class.[50]

Moeller van den Bruck described the Conservative Revolution as the intention to keep a set of values connected to a Volk (people). These lasting values could endure through changing times due to innovations in how they are organized and understood. Unlike the rigid reactionaries, who don’t create anything, and the pure revolutionaries, who only destroy, the Conservative Revolutionary aimed to shape things in a lasting way that ensures their survival:[51]

- Conserving is not just about passing down what we received, but about updating the structures and ideas to stay rooted in strong values, even with ongoing historical challenges. In an age of uncertainty, opposing the past is not enough; we must create new security by embracing the same risks that come with it. — Arthur Moeller van den Bruck[52]

Edgar Jung rejected the idea that true conservatives wanted to "stop history."[53] The life they wanted to create, according to Oswald Spengler, was not based on any moral rules, but on "a clear, natural morality from good upbringing." This morality wasn't developed through thought, but was more like an instinct that has its own reasoning.[54] Conservative revolutionaries viewed moral values as natural and timeless, and they believed these were reflected in rural life. Spengler argued that this rural way of life was threatened by the city's artificial nature, which required theories and ideas to understand life, either from liberal democrats or scientific socialists. The goal of Conservative Revolutionaries was to bring back what they viewed as natural laws and values in the modern world:[55]

- We call Conservative Revolution the return of essential laws and values, without which humans lose their ties to Nature and God and can't create real order. — Edgar Jung, 1932[56]

Influenced by Nietzsche, many opposed Christian ideas of helping each other and equality. Although a lot of Conservative Revolutionaries identified as Protestant or Catholic, they believed Christian principles forced the strong to help the weak when it should be a choice.[57] On a global level, movement thinkers imagined a world where nations would ignore moral rules in their dealings with each other, following only their own interests.[3]

- Let thousands, even millions, die; how does their suffering matter compared to a state that absorbs all the worries and desires of the German identity! — Friedrich Georg Jünger, 1926.[58]

The Völkischen were part of a racial and occult movement from the mid-19th century that affected the Conservative Revolution. They focused on opposing Christianity and wanted to return to a (reconstructed) German pagan belief or change Christianity to remove non-German (Semitic) influences.[59]

Volksgemeinschaft and dictatorship

[change | change source]

Thomas Mann thought that during World War I, Germany's military resistance to the West was stronger than its spiritual resistance. He believed this was mainly because the character of the German national community couldn't easily express itself in words, which made it hard to effectively challenge the strong arguments from the West. Since German culture was seen as a matter of the soul, not just something the mind could understand,[61] Mann believed the authoritarian state was what the German people naturally wanted. He argued that politics was always tied to democracy and therefore did not fit the German spirit.[62]

- There is no real democratic or conservative politician. You are either a politician or you are not, and if you are, you are a democrat. — Thomas Mann, 1915[61]

Some scholars have argued whether these ideas are artistic and idealistic, or if they are a serious effort to analyze the politics of the time. Young Mann's writings have strongly influenced many Conservative Revolutionaries.[63] In 1922, the right criticized Mann for softening his undemocratic views after he removed parts from his book, Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen ('Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man'), first published in 1918.[64] In a speech in the same year, 'On the German Republic', Mann openly supported the Weimar Republic and criticized figures linked to the Conservative Revolution, like Oswald Spengler, whom he called dishonest and immoral.[60] In 1933, he called National Socialism the 'political reality of that Conservative Revolution.'[65]

In 1921, Carl Schmitt wrote his essay Die Diktatur ('The Dictatorship'), where he examined the basics of the newly created Weimar Republic. He compared the strong and weak parts of the new constitution and pointed out that the role of the Reichspräsident was important, mainly because Article 48 gave the president the power to declare a state of emergency, which Schmitt quietly supported as a dictatorial power.[66]

- If a state's constitution is democratic, then any rejection of democratic rules and any use of state power without the majority's approval can be seen as dictatorship.— Carl Schmitt, 1921[67]

Schmitt argued in Politische Theologie (1922) that a legal system cannot work without a supreme authority. He described sovereignty as the ability to declare a "state of emergency," which means setting aside the usual laws: "If there is someone in a government who can completely pause the law and then use outside legal means to restore order, that person is the sovereign in that government."[68] He believed that every government should have in its rules the power to act quickly and effectively without needing long discussions in parliament.[69] In 1934, he referenced Adolf Hitler to explain the actions taken during the Night of the Long Knives, stating: Der Führer schützt das Recht ('The leader defends the law').[70]

Front-line socialism

[change | change source]Socialists generally agreed on getting rid of the worst parts of capitalism.[71] Jung said that, while the economy should stay private, the greed of capital needs to be kept in check, and a community based on shared interests should be created between workers and employers. Another reason for dislike of capitalism was the profits made from war and inflation. Finally, many Conservative Revolutionaries were from the middle class, which made them feel trapped in the struggle between the wealthy capitalists and the threatening masses.[72]

Even though they rejected communism as just a dream, many relied on some Marxist terms in their writings. For example, Jung highlighted the 'inevitable history' of conservatism replacing the liberal age, similar to the historical materialism of Karl Marx. Spengler discussed the decline of the West as an unavoidable trend, but he aimed to offer readers a 'new socialism' that would help them understand the meaninglessness of life, unlike Marx's vision of a paradise on earth. Mostly, the Conservative Revolution was influenced by vitalism and irrationalism, not materialism. Spengler believed Marx's materialist view came from nineteenth-century science, while the twentieth century would focus on psychology.

- We don't believe reason has power over life anymore. We think life is what controls reason.— Oswald Spengler, 1932[73]

Ernst Niekisch, along with Karl Otto Paetel and Heinrich Laufenberg, was a key supporter of National Bolshevism, a small part of the Conservative Revolution seen as the 'left-wing of the right.' They promoted an extreme form of nationalism mixed with socialism, rejecting all Western influences on German culture, including liberalism, democracy, capitalism, Marxism, the middle class, the working class, Christianity, and humanism. Niekisch and the National Bolsheviks were even willing to team up temporarily with German communists and the Soviet Union to destroy the capitalist West.[74]

Currents

[change | change source]In his PhD thesis guided by Karl Jaspers, Armin Mohler identified five groups within the Conservative Revolution: the young conservatives, the national revolutionaries, the folkish group, the leaguists, and the rural people's movement. Mohler noted that the last two groups focused more on action than on theory, with the rural movement providing direct resistance through protests and tax boycotts.[75]

French historian Louis Dupeux identified five divisions within the Conservative Revolutionaries. Small farmers differed from cultural pessimists and 'pseudo-moderns', mainly from the middle class. Supporters of an 'organic' society were different from those favoring an 'organized' society. A third division separated those who wanted major political and cultural changes from those who wanted a quick social revolution, even at the expense of economic freedom and private property. The fourth division focused on the 'drive to the East' and how to view Bolshevik Russia, debating Germany's position between a 'declining' West and a 'young and barbaric' East. The last division was a strong disagreement between the Völkischen and pre-fascist thinkers.[76]

In 1995, historian Rolf Peter Sieferle talked about five groups in the Conservative Revolution: the 'völkischen', the 'national socialists', the 'revolutionary nationalists', the 'vital-activists', and a smaller group called the 'biological naturalists'.[77]

Using earlier research by Mohler and Dupeux, French political scientist Stéphane François outlined the three key trends in the Conservative Revolution, which is the most common division among those studying the movement:

- the "young conservatives" (Jungkonservativen);[78]

- the "national revolutionaries" (Nationalrevolutionäre);[79]

- the Völkischen (from the Völkisch movement).[80]

Young conservatives

[change | change source]

"Young conservatives" were greatly affected by 19th-century ideas and styles like German romanticism and cultural pessimism. Unlike older Wilhelmine conservatives, the Jungkonservativen wanted to help bring back important and basic values—authority, the state, the community, the nation, and the people—while also being in tune with their time.[5]

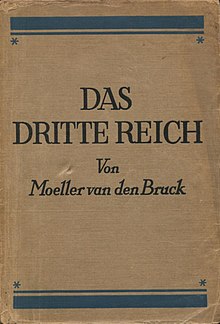

Moeller van den Bruck attempted to solve the issue of Kulturpessimismus by opposing decline to create a new political system.[34] In 1923, he published the important book Das Dritte Reich ('The Third Reich'), where he moved from theory to propose a practical plan to improve the political situation: a 'Third Reich' that would bring all classes together under a strict government that mixed right-wing nationalism and left-wing socialism.[13][82]

The Jung Conservatives rejected both a nation-state made up of one group of people and an imperial system based on various ethnic groups. [83]Their goal was to achieve the Volksmission ("mission of the people") by creating a new Reich, meaning "the uniting of all peoples in a larger state, led by one guiding principle, under the main control of just one people," according to Armin Mohler.[75] Edgar Jung summarized this in 1933:

- The idea of the nation-state is moving personal beliefs from people to the state itself. [...] The super-state (the Reich) is a type of government that operates above the people and can keep them separate. However, it does not aim to be completely controlling and will acknowledge local powers and independence.— Edgar Jung, 1933[84]

Even though Moeller van der Bruck took his own life in May 1925 due to despair, his ideas still affected people of his time. One of them was Edgar Jung, who pushed for a corporatist state without class struggles or parliamentary democracy, aiming to bring back the spirit of the Middle Ages with a new Holy Roman Empire in central Europe[34]. The idea of returning to medieval values and styles among 'young conservatives' came from a Romantic love for that time, which they saw as simpler and more united than today.[85] Oswald Spengler admired medieval chivalry as the right way to stand against the decline of modern times.[54] Jung viewed this change as a slow process, much like the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, rather than a sudden uprising like the French Revolution.[13]

National revolutionaries

[change | change source]

Other conservative revolutionaries were influenced by their experiences during the First World War. Unlike the 'young conservatives' who worried about culture, Ernst Jünger and the national revolutionaries fully accepted modern techniques and used tools like propaganda and mass groups to overcome modern challenges and create a new political system.[87] This system would be based on real life rather than just ideas, built on natural and structured communities, and led by a new group of capable leaders.[88] Historian Jeffrey Herf called this idea 'reactionary modernism', which means having excitement for modern technology while rejecting Enlightenment ideas and liberal democracy.[89]

- That time is only worth wasting. But to waste it, you must understand it first. [...] You had to fully commit to the method, by mastering it in the end. [...] The tool itself was not worthy of praise — that was the risky part — it just needed to be used.— Franz Schauwecker, 1931[90]

Jünger supported the rise of a new group of young intellectuals that would come from the trenches of WWI, ready to challenge capitalist society and represent a fresh nationalist revolutionary spirit. In the 1920s, he wrote over 130 articles in different nationalist magazines, mainly in Die Standarte or, less often, in Widerstand, the publication linked to Ernst Niekisch. However, as Dupeux noted, Jünger wanted to use nationalism as something powerful but not final, allowing the new order to develop on its own.[34] The connection between Jünger and the Conservative Revolutionaries is still debated among scholars.[91]

Germany joined the League of Nations in 1926, which helped push the revolutionary side of the movement to become more extreme in the late 1920s. This was viewed as a sign of Western influence in a country that Conservative Revolutionaries imagined as the future Empire of Central Europe.[14]

Völkischen

[change | change source]The word völkisch comes from the German idea of Volk (similar to the English word folk), which includes meanings of 'nation', 'race', and 'tribe'.[92] The Völkisch movement started in the mid-1800s and was influenced by German Romantic ideas. It was based on the idea of Blut und Boden ('blood and soil') and was about race, popular feelings, farming, romantic nationalism, and antisemitism from the 1900s. Armin Mohler said that the Völkischen wanted to fight against 'desegregation' that was seen as a threat to the Volk by helping people become aware of their identity.[93]

Inspired by writers like Arthur de Gobineau, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, and Ludwig Woltmann, the Völkischen developed a view of races that put Aryans (or Germans) at the top of the 'white race'. They used phrases like 'Nordic race' and 'Germanic peoples', but their idea of Volk could also mean a 'common language'[94] or an 'expression of a landscape's soul', according to geographer Ewald Banse[95]. The Völkischen romanticized the idea of an 'original nation', which they believed could still be found in rural Germany, structured as a form of 'primitive democracy led by their natural leaders.' For the Völkischen, the idea of 'people' (Volk) became a living and eternal being, similar to how they might write about 'Nature', instead of just a sociological group.[96]

The political unrest after WWI created a good environment for the comeback of various Völkisch groups that were common in Berlin then.[34] The Völkischen became important by the number of groups during the Weimar Republic,[97] even though they did not have many followers.[34] Some Völkischen aimed to bring back what they thought was a true German religion by bringing back the worship of ancient German gods.[98] Different occult movements like Ariosophy were linked to Völkisch ideas, and there were also many artists among them, such as painters Ludwig Fahrenkrog and Fidus.[34] By May 1924, Wilhelm Stapel saw the movement as able to unite the entire nation: he believed the Völkischen had a vision to promote instead of a political plan, and they were led by 'heroes' not 'calculating politicians.'[99]

Mohler mentioned these people as part of the Völkisch movement: Theodor Fritsch, Otto Ammon, Willibald Hentschel, Guido von List, Erich Ludendorff, Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, Herman Wirth, and Ernst Graf zu Reventlow.[93]

Relationship to Nazism

[change | change source]

Even though they share significant intellectual ideas, this separate movement cannot be directly compared to Nazism.[100] Their anti-democratic and militaristic views definitely helped make the idea of an authoritarian government accepted by some educated middle-class people and youth,[101] but the writings of Conservative Revolutionaries did not strongly shape National Socialist beliefs.[102] Historian Helga Grebing points out that whether people were open to National Socialism is not the same as understanding its roots and ideas.[103] This unclear connection has led some experts to describe the movement as a kind of 'German pre-fascism'[76] or 'non-Nazi fascism'.[104]

In the 1920s to early 1930s, as the Nazi Party became powerful, some thinkers, as historian Roger Woods notes, failed to see the true nature of the Nazis. Their political problems and inability to clearly describe a new German government meant there were no strong alternatives from the right, leading to little resistance against the Nazis taking control.[105] Historian Fritz Stern adds that many conservative revolutionaries, even with doubts about Hitler's tactics, viewed him as their only chance to succeed. However, after Hitler's rise, many of Moeller's supporters lost faith, and the twelve years of the Third Reich showed a split between conservative revolution and national socialism.[106]

A few months after their big election win, the Nazis rejected Moeller van den Bruck and claimed he was not a predecessor of National Socialism. They called his ideas 'unrealistic' and said in 1939 that they had 'nothing to do with actual history or practical politics' and that Hitler 'was not Moeller's heir.'[102] Conservative Revolutionaries often had mixed feelings about the Nazis,[107] but many turned against Nazism and the Nazi party after they took power in 1933.[108] Some opposed its totalitarian and antisemitic nature, while others would have preferred a different kind of authoritarian regime. Stern summed up the relationship like this:

- But we must ask, could there have been another 'Third Reich'? Can we reject reason, praise force, foresee the time of the empire's dictator, and condemn all current systems, without paving the way for the success of irresponsibility? The German critics did all this, showing the serious risks of politics based on cultural hopelessness.— Fritz Stern, 1961[102]

Opponents

[change | change source]Many Conservative Revolutionaries opposed liberalism and supported the idea of a 'strong leader,' but they did not agree with the totalitarian or antisemitic aspects of the Nazi regime. Martin Niemöller, who initially backed Adolf Hitler, opposed the Nazis’ control over German Protestant churches in 1934 and their Aryan Paragraph.[109] Although he made some comments about Jews that some scholars view as antisemitic, he led the anti-Nazi Confessing Church.

- We chose to stay quiet. We are not innocent, and I keep thinking, what if in 1933 or 1934—there must have been a chance—14,000 Protestant pastors and all Protestant groups in Germany had stood up for what was right until the end? What if we had spoken out then, saying it was wrong for Hermann Göring to put 100,000 Communists in concentration camps to let them die?— Martin Niemöller, 1946[110]

Rudolf Pechel and Friedrich Hielscher openly challenged the Nazi government, while Thomas Mann fled in 1939 and sent anti-Nazi speeches to Germany through the BBC during the war. Ernst Jünger turned down a position in the Nazi Reichstag both in 1927 and 1933, hated the "blood and soil" idea,[111] and his home was searched multiple times by the Gestapo. Hermann Rauschning and Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus found safety abroad to continue opposing the regime. Georg Quabbe refused to work with the Nazis as a lawyer.[112] Just before he died in 1936, Oswald Spengler predicted that "in ten years, a German Reich probably won’t exist anymore."[113] In his private writings, he strongly criticized Nazi anti-Semitism.

- Anti-Semitism often hides a lot of jealousy towards what others can do that one can't. [...] When someone would rather ruin businesses and education than accept Jews in those areas, they are being extreme, which is harmful to society. Foolish.— Oswald Spengler[114]

Others like Claus von Stauffenberg stayed in the Reichswehr and later the Wehrmacht to quietly plot the July 20th attempt to remove Hitler in 1944. Fritz Stern noted that it showed the real spirit of the conservative movement that the conditions of the Third Reich led many of them to oppose it, sometimes quietly, often openly and at great cost. [...] In the last attempt against Hitler in July 1944, a few former conservative revolutionaries risked and lost their lives, becoming martyrs for the true beliefs they once had.

Competitors

[change | change source]

Some Conservative Revolutionaries did not completely oppose the fascist nature of Nazi rule, but would have liked a different kind of authoritarian Government. They were often killed or jailed for not following the Führerprinzip.

Edgar Jung, an important leader of the Conservative Revolution, was killed during the Night of the Long Knives by Heinrich Himmler's SS, who wanted to stop other nationalist ideas from challenging Hitler's beliefs. For many in the Conservative Revolution, this event ended their mixed feelings about the Nazis. Jung advocated for a unified view of the Conservative Revolution, describing nations as whole living entities, criticizing individualism, and supporting militarism and war. He also backed the complete use of human and industrial resources, while promoting the benefits of modernity, much like the futurism of Italian Fascism.[115]

Ernst Niekisch, who was against Jews and supported a strong government, did not like Adolf Hitler because he thought Hitler did not have real socialism. Instead, he looked to Joseph Stalin as a model for strong leadership. He was held in a concentration camp from 1937 to 1945 for criticizing the government.[116] August Winnig, who initially supported the Nazis in 1933, later opposed the Third Reich due to his neo-pagan beliefs. Despite writing a popular essay in 1937[117] that defended fascism and was full of antisemitism, which did not completely match Nazi ideas about race,[118] he was mostly ignored by the Nazis because he stayed quiet during Hitler's rule.

Collaborators

[change | change source]Known as the main lawyer of the Third Reich,[119] Carl Schmitt did not regret his part in making the Nazi state even after 1945.[68] While he thought Adolf Hitler was too crude,[115] Schmitt took part in burning books by Jewish writers, celebrating the destruction of things he saw as un-German and anti-German, and asking for a bigger cleanup that included writers influenced by Jewish ideas.[120]

Hans Freyer was the leader of the German Institute for Culture in Budapest from 1938 to 1944. Along with Nazi historian Walter Frank, Freyer created a racist and anti-Jewish history during this time.[121] Wilhelm Stapel joined the Deutsche Christen in July 1933 and strongly opposed the anti-Nazi Confessing Church led by Martin Niemöller and Karl Barth. He also supported the introduction of the Aryan paragraph in the Church. At the same time, Stapel worked with Reichsminister of Church Affairs Hanns Kerrl as his advisor.[122] However, due to pressure from the Nazi leaders in 1938, he had to stop publishing his monthly magazine Deutsches Volkstum.[123]

Study and debate

[change | change source]The early study of the Conservative Revolution began with the French historian Edmond Vermeil, who wrote an essay in 1938 called Doctrinaires de la révolution allemande 1918–1938 ("Doctrinarians of the German Revolution 1918–1938").[34] In the years right after WWII, many of the political thinkers who focused on the Conservative Revolution were far-right individuals strongly influenced by thinkers like Armin Mohler and Alain de Benoist. It wasn't until the 1980s and 1990s that research on this movement started to gain more attention across different political views, mainly because of its links to Nazism and its impact on the post-war European New Right.[3]

Post-war revival after Armin Mohler

[change | change source]The modern idea of a "Conservative Revolution" was formed after WWII by philosopher Armin Mohler in his 1949 doctoral thesis, titled Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932, supervised by Karl Jaspers. Mohler referred to Conservative Revolutionaries as the "Trotskyites of the German Revolution" and has often been accused of trying to reshape a pre-WWII far-right movement to fit a post-fascist Europe by downplaying the role of these thinkers in the rise of Nazism.[124] The work was called "a handbook" and, according to historian Roger Griffin, was meant as a guide for those wanting to keep their values in today's world. Mohler thought the "Conservative Revolution" project had just been delayed by the Nazis taking power.[125] At that time, he was also the secretary for Ernst Jünger, a key figure in the movement.[126]

In the 1970s, thinkers from the Conservative Revolution influenced new radical right movements, like the French Nouvelle Droite, led by Alain de Benoist.[127] Some scholars, mainly in West Germany, started to question Mohler's work due to his political ties to the idea. The reactionary and anti-modern aspects of the 'Conservative Revolution' were mainly highlighted during that decade, and many viewed the movement as just a breeding ground for Nazism, sharing similar totalitarian views.[128]

German-American historian Fritz Stern used the term "Conservative Revolution" in his 1961 book The Politics of Cultural Despair to describe the life and ideas of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. He highlighted the feelings of disconnection and "cultural despair" these writers had in the early modern world, which pushed them to share radical ideas. However, Stern placed Moeller van den Bruck within a bigger "Germanic ideology" that included earlier thinkers from the late 19th century like Paul de Lagarde and Julius Langbehn.[11]

Academic research since the 1980s

[change | change source]In a 1981 meeting called "Conservative Revolution and Modernity", French historian Louis Dupeux noted that what Mohler called the "Conservative Revolution" was not really reactionary or completely against modern ideas (some were even hopeful about the modern world).[5] Three years later, American historian Jeffrey Herf backed this up in his book Reactionary Modernism, which showed that conservative thinkers of that time accepted modern techniques but rejected liberal democracy.[129] Dupeux also pointed out that Conservative Revolutionaries opposed both forms of progressivism, which were liberalism and Marxism, and the cultural pessimism of reactionaries and conservatives. They tried to solve this by suggesting new types of reactionary governments that could fit into the modern world.[5]

In his 1993 book Anatomy of the Conservative Revolution, German sociologist Stefan Breuer rejected Mohler's definition of "Conservative Revolution". He defined "conservatism" as wanting to keep the feudal structures of Germany, which were already dying during the Weimar period. Breuer saw Mohler's idea of the "Conservative Revolution" as a reflection of a new modern society aware of the problems of a simple modernity based only on science and technology. While he recognized the complexity of classifying that time intellectually, Breuer said he would have preferred the term "new nationalism" to describe a more engaging and complete version of German right-wing movements, as opposed to the "old nationalism" of the 19th century, which mainly focused on preserving traditional institutions and German influence globally.[130]

In 1996, British historian Roger Woods recognized that the idea was valid, but he emphasized that the movement was diverse and had trouble agreeing on a common plan, a political standstill he called the "conservative dilemma." Woods described the Conservative Revolution as "ideas that can't be simply explained as a political program, but are more like expressions of tension."[131] About the unclear connection with Nazism, which Mohler minimized in his 1949 thesis and 1970s analysts highlighted, Woods said that "even with some Conservative Revolutionary critiques of the Nazis, there remains a strong commitment to action, leadership, hierarchy, and a disregard for political programs. [...] Ongoing political issues lead to activism and a focus on hierarchy, which means there can be no strong opposition to the National Socialist rise to power."[105]

Historian Ishay Landa has explained that the Conservative Revolution's idea of "socialism" is actually very capitalist.[132] Landa indicates that Oswald Spengler's "Prussian Socialism" was strongly against labor strikes, trade unions, higher taxes on the wealthy, shorter workdays, and any government help for sickness, old age, accidents, or job loss.[132] While rejecting any social welfare policies, Spengler praised private property, competition, imperialism, wealth gathering in the hands of the few elites, and capital growth.[132] Landa describes Spengler's "Prussian Socialism" as working a lot for the least pay but being satisfied with it.[132] Landa also describes Arthur Moeller van den Bruck as a "socialist supporter of capitalism" who valued free trade, active markets, the creativity of entrepreneurs, and the capitalist division of labor, aiming to replicate British and French imperialism.[133] Landa points out that Moeller's criticism of socialism shares similarities with those of neoliberals like Friedrich von Hayek and states that "Moeller's writing is far from being against the capitalist spirit; it is full of it."[133]

Later influence

[change | change source]The movement affected modern thinkers outside of German-speaking Europe. One notable figure is the Italian philosopher Julius Evola, who is linked to the Conservative Revolution.[40]

The Nouvelle Droite, a French far-right group formed in the 1960s, aimed to adapt traditional and ethnically focused politics to post-WWII Europe and to separate itself from older far-right movements like fascism, mainly through a shared European nationalism.[134] This group has been greatly shaped by the Conservative Revolution[127][135] and its German counterpart, the Neue Rechte.[136]

The ideas and framework of the Identitarian movement are largely influenced by the Nouvelle Droite, the Neue Rechte, and through them, the Conservative Revolution.[source?]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ Dupeux 1994, pp. 471–474; Woods 1996, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Breuer 1993, pp. 194–198; Woods 1996, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Woods 1996, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Feldman 2006, p. 304.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Dupeux 1994, pp. 471–474.

- ↑ Breuer 1993, pp. 194–198; Woods 1996, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Breuer 1993, pp. 194–198; Merlio 2003, p. 130.

- ↑ Giubilei 2019, p. 2.

- ↑ Dupeux 1994, pp. 471–474; Dupeux 2005, p. 3.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bar-On 2011, p. 333.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Stern 1961.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 29; François 2009.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Dupeux 1994, pp. 474–475.

- ↑ Stern 1961, p. 296; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 29; François 2009; see for instance: Oswald Spengler, "Nietzsche und sein Jahrhundert" (speech of October 1924), in Reden und Aufsiitze, 3rd ed. (Munich: Beck, 1951), pp. 110–24 (pp. 12–13); Jünger, Ernst (1929). Das Wäldchen 125: eine Chronik aus den Grabenkämpfen, 1918. E. S. Mittler. p. 154.

- ↑ Stern 1961, p. 294; Woods 1996, pp. 30–31, 42–43, 57–58.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Breuer 1993, p. 21.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 1–2, 7–9.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 1–2, 7–9; Bar-On 2011, p. 333; see Jünger 1926, p. 32.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 379–380; François 2009; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 467–469; François 2009; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 379–380; François 2009; see also Wolin, Richard (1992). "Carl Schmitt: The Conservative Revolutionary Habitus and the Aesthetics of Horror". Political Theory. 20 (3): 424–25. doi:10.1177/0090591792020003003. S2CID 143762314.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, p. 379–380; Kroll 2004; François 2009.

- ↑ François 2009; Feldman 2006, p. 304.

- ↑ François 2009; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 519–521; François 2009.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, p. 479.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, p. 470; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, p. 472; Sieferle 1995, p. 196.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 467–469; François 2009.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 62, 372; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ 34.00 34.01 34.02 34.03 34.04 34.05 34.06 34.07 34.08 34.09 34.10 34.11 François 2009.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, p. 470.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 110–112, 415.

- ↑ Sieferle 1995, p. 74; François 2009.

- ↑ Stern 1961, p. 295; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Stern 1961, p. 295.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Boutin 1992, p. 513; Hakl 1998.

- ↑ Feldman 2006, p. 304; François 2009.

- ↑ Feldman 2006, p. 304; François 2009.

- ↑ Herf 1986, p. 39.

- ↑ Sieferle 1995.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Poewe, Karla O. (2006). New Religions and the Nazis. Routledge. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9780415290258.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Weiß 2017, pp. 40–45.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 111.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 61.

- ↑ de Benoist 2014.

- ↑ Balistreri 2004.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 61; see Jung 1933.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Spengler 1923, pp. 891, 982.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 103.

- ↑ Jung 1932, p. 380.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 31–32, 37–40; François 2009.

- ↑ Fest, Joachim E. (1999). The Face of the Third Reich: Portraits of the Nazi Leadership. Da Capo Press. pp. 249–263.

- ↑ Boutin 1992, pp. 264–265; Koehne 2014.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Lee, Frances (2007). Overturning Dr. Faustus: Rereading Thomas Mann's Novel in Light of Observations of a Non-political Man. Camden House. p. 212.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Mann 1968, pp. 22–29.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 102.

- ↑ Kroll 2004.

- ↑ Keller, Ernst (1965). Der unpolitische Deutsche: Eine Studie zu den "Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen" von Thomas Mann. Francke Verlag. p. 130.; Kurzke, Hermann (1999). Thomas Mann: das Leben als Kunstwerk. Beck. p. 360. ISBN 9783406446610.

- ↑ Mendelsohn, Peter de (1997). Thomas Mann: Tagebücher 1933–1934. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer. p. 194.

- ↑ Agamben 2005.

- ↑ Die Diktatur Archived 2013-01-24 at the Wayback Machine § XV p. 11.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Vinx 2010.

- ↑ Agamben 2005, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Schmitt 1934.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 61–62, quoting "Die nationale Revolution", Deutsches Volkstum, 11 August 1929, p. 575.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Spengler 1932, pp. 83–86.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 70; see for instance: Lt. Richard Scheringer, "Revolutionare Weltpolitik", Die sozialistische Nation: Blatter der Deutschen Revolution, 6 June 1931.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Mohler 1950.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Dupeux 1992.

- ↑ Sieferle 1995, p. 25.

- ↑ Mohler 1950; Dupeux 1994, pp. 471–474.

- ↑ Mohler 1950; Dupeux 1994, pp. 471–474}.

- ↑ Mohler 1950; Dupeux 1994, pp. 471–474.

- ↑ Mohler 1950; François 2009.

- ↑ Burleigh, Michael (2001). The Third Reich: A New History. Pan. p. 75. ISBN 9780330487573.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 172–176; François 2009.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, p. 174, quoting: Edgar Julius Jung, Sinndeutung der deutschen Revolution. In: Schriften an die Nation, Band 55. Oldenburg 1933, pp. 78, 95.

- ↑ Dupeux 1994, pp. 471–474; see also Joachim H. Knoll, "Der Autoritare Staat. Konservative Ideologie und Staatstheorien am Ende der Weimarer Republik," in Lebendiger Geist, 1959. pp. 200-224.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 176–181; François 2009.

- ↑ Mohler 1950, pp. 176–181; François 2009.

- ↑ François 2009; see also Mommsen, Hans (1997). Le National-socialisme et la société allemande: Dix essais d'histoire sociale et politique [National Socialism and German Society: Ten Essays on Social and Political History]. Les Editions de la MSH. ISBN 9782735107575.

- ↑ Herf 1986.

- ↑ Schauwecker, Franz (1931). Deutsche allein – Schnitt durch die Zeit [Germans alone - cut through time]. p. 162.

- ↑ Schloßberger, Matthias. "Ernst Jünger und die "Konservative Revolution". Überlegungen aus Anlaß der Edition seiner politischen Schriften" [Ernst Jünger and the "Conservative Revolution". Considerations on the occasion of the edition of his political writings]. iaslonline.de.

- ↑ James Webb. 1976. The Occult Establishment. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court. ISBN 0-87548-434-4. pp. 276–277

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Mohler 1950, pp. 81–83, 166–172.

- ↑ Georg Schmidt-Rohr: Die Sprache als Bildnerin. 1932.

- ↑ Banse 1928, p. 469.

- ↑ Dupeux 1992, pp. 115–125.

- ↑ Lutzhöft, Hans-Jürgen (1971). Der Nordische Gedanke in Deutschland 1920-1940. Klett. p. 19. ISBN 9783129054703.

- ↑ Boutin 1992, pp. 264–265.

- ↑ Wilhelm Stapel, "Das Elementare in der volkischen Bewegung", Deutsches Volkstum, 5 May 1924, pp. 213–15.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 111–115.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 2–4; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 Stern 1961, p. 298.

- ↑ Woods 1996, pp. 2–4.

- ↑ Bar-On 2011, p. 333; Feldman 2006, p. 304.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Woods 1996, p. 134.

- ↑ Stern 1961, pp. 296–297.

- ↑ Bullivant 1985, p. 66.

- ↑ Stern 1961, p. 298; Klapper 2015, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Martin Stöhr, „...habe ich geschwiegen“. Zur Frage eines Antisemitismus bei Martin Niemöller

- ↑ "Niemöller, origin of famous quotation "First they came for the Communists..."".

- ↑ Barr, Hilary Barr (24 June 1993). "An Exchange on Ernst Jünger". New York Review of Books. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Bronder, Dietrich (1964). Bevor Hitler kam: eine historische Studie [Before Hitler came: a historical study]. Pfeiffer. p. 25.

- ↑ Farrenkopf, John (2001). Prophet of Decline: Spengler on World History and Politics. LSU Press. pp. 237–238. ISBN 9780807127278.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Griffin, Roger (ed). 1995. "The Legal Basis of the Total State" – by Carl Schmitt. Fascism. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Philip Rees, Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right Since 1890, 1990, p. 279

- ↑ Pöpping, Dagmar (2016). Kriegspfarrer an der Ostfront: Evangelische und katholische Wehrmachtseelsorge im Vernichtungskrieg 1941–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 37. ISBN 9783647557885.

- ↑ Nurdin, Jean (2003). Le Rêve européen des penseurs allemands (1700–1950). Presses Univ. Septentrion. p. 222. ISBN 9782859397760.

- ↑ Frye, Charles E. (1966). "Carl Schmitt's Concept of the Political". The Journal of Politics. 28 (4): 818–830. doi:10.2307/2127676. ISSN 0022-3816. JSTOR 2127676. S2CID 155049623.

- ↑ Claudia Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, p. 59 ISBN 0-674-01172-4

- ↑ The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 4: 1800–1945, by Stuart Macintyre, D. Daniel R. Woolf, Andrew Feldherr, 2011, p. 178.

- ↑ Gailus, Manfred; Vollnhals, Clemens (2016). Für ein artgemäßes Christentum der Tat: Völkische Theologen im "Dritten Reich". Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 97–117. ISBN 9783847005872.

- ↑ Mayer, Michael (2002). "NSDAP und Antisemitismus 1919–1933". Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

- ↑ Bar-On 2011, p. 333; Weiß 2017, pp. 40–45; see also Eberhard Kolb, Dirk Schumann: Die Weimarer Republik (= Oldenbourg Grundriss der Geschichte, Bd. 16). 8. Auflage. Oldenbourg, München 2013, p. 225.

- ↑ Griffin, Roger (2000). "Between metapolitics and apoliteia : The Nouvelle Droite's strategy for conserving the fascist vision in the 'interregnum'". Modern & Contemporary France. 8 (1): 35–53. doi:10.1080/096394800113349. ISSN 0963-9489. S2CID 143890750.

- ↑ Merlio 2003, p. 125.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 François 2017.

- ↑ Merlio 2003, p. 127; see for instance: Jean-Pierre Faye, Languages totalitaires, Paris, 1972; Johannes Petzold, Konservative Theoretiker des deutschen Faschismus, Berlin-Ost, 1978.

- ↑ Herf 1986; Merlio 2003, p. 128.

- ↑ Merlio 2003, p. 130.

- ↑ Woods 1996, p. 6.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 132.2 132.3 Landa, Ishay (2012). The Apprentice's Sorcerer: Liberal Tradition and Fascism. Haymarket Books. pp. 60–65.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Landa, Ishay (2012). The Apprentice's Sorcerer: Liberal Tradition and Fascism. Haymarket Books. pp. 119–128.

- ↑ Schlembach, Raphael (2016). Against Old Europe: Critical Theory and Alter-Globalization Movements. Routledge. ISBN 9781317183884.

- ↑ Bar-On, Tamir (2011b). "Transnationalism and the French Nouvelle Droite". Patterns of Prejudice. 45 (3): 200. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2011.585013. ISSN 0031-322X. S2CID 144623367.

- ↑ Pfahl-Traughber 1998, pp. 223–232.

Primary sources

[change | change source]- Banse, Ewald (1928). Landschaft und Seele. München.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - de Benoist, Alain (1994). "Nietzsche et la Révolution conservatrice". Le Lien. GRECE.

- de Benoist, Alain (2014). Quatre figures de la révolution conservatrice allemande : Sombart, van der Bruck, Niekisch, Spengler. Les Amis d'Alain de Benoist. ISBN 9782952832175.

- Jung, Edgar Julius (1932). Deutschland und die konservative Revolution.

- Jung, Edgar Julius (1933). Sinndeutung der deutschen revolution. G. Stalling.

- Jünger, Ernst (1926). Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis. Mittler.

- Mann, Thomas (1968). Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen, Das essayistische Werk. Vol. 1. Fischer.

- Mohler, Armin (1950). Die konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918-1932 : ein Handbuch (2005 ed.). Ares. OCLC 62229724.

- Schmitt, Carl (1934). "Der Führer schützt das Recht". Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung (38). (trans. as "The Führer Protects Justice" in Detlev Vagts, Carl Schmitt's Ultimate Emergency: The Night of the Long Knives (2012) 87(2) The Germanic Review 203.)

- Spengler, Oswald (1923). Untergang des Abendlandes. Vol. 2. Oskar Beck.

- Spengler, Oswald (1932). Politische Schriften. Volksausgabe.

Bibliography

[change | change source]- Agamben, Giorgio (2005). State of Exception. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226009247.

- Bar-On, Tamir (2011). Backes, Uwe; Moreau, Patrick (eds.). Intellectual Right - Wing Extremism – Alain de Benoist's Mazeway Resynthesis since 2000 (1 ed.). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 333–358. doi:10.13109/9783666369223.333. ISBN 9783525369227.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Balistreri, Giuseppe (2004). Filosofia della konservative Revolution : Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. Lampi di stampa. ISBN 88-488-0267-2.

- Bullivant, Keith (1985). "The Conservative Revolution". In Phelan, Anthony (ed.). The Weimar Dilemma: Intellectuals in the Weimar Republic. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1833-6.

- Boutin, Christophe (1992). Politique et tradition: Julius Evola dans le siècle, 1898-1974. Editions Kimé. ISBN 9782908212150.

- Breuer, Stefan (1993). Anatomie der Konservativen Revolution (2009 ed.). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft (WBG). ISBN 978-3534191963.

- Dupeux, Louis (1979). National bolchevisme: stratégie communiste et dynamique conservatrice. H. Champion. ISBN 9782852030626.

- Dupeux, Louis (1992). La Révolution conservatrice allemande sous la République de Weimar. Paris: Kimé. ISBN 978-2908212181.

- Dupeux, Louis (1994). "La nouvelle droite "révolutionnaire-conservatrice" et son influence sous la république de Weimar". Revue d'Histoire Moderne & Contemporaine. 41 (3): 471–488. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1994.1732.

- Dupeux, Louis (2005). "Die Intellektuellen der konservativen Revolution und ihr Einfluß zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik". In Schmitz, Walter; Vollnhals, Clemens (eds.). Völkische Bewegung--Konservative Revolution--Nationalsozialismus : Aspekte einer politisierten Kultur. Thelem. ISBN 978-3935712187.

- Feldman, Matthew (2006). "Heidegger, Martin". In Blamires, Cyprian (ed.). World Fascism. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-940-9.

- François, Stéphane (2009). "Qu'est ce que la Révolution Conservatrice ?". Fragments sur les Temps Présents.

- François, Stéphane (2017). "La Nouvelle Droite et le nazisme. Retour sur un débat historiographique". Revue Française d'Histoire des Idées Politiques. 46 (2): 93–115. doi:10.3917/rfhip1.046.0093.

- Giubilei, Francesco (2019). The History of European Conservative Thought. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781621579090.

- Hakl, Hans Thomas (1998). "Julius Evola und die deutsche Konservative Revolution". Criticon (158): 16–32.

- Herf, Jeffrey (1986). Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33833-6.

- Klapper, John (2015). Nonconformist Writing in Nazi Germany: The Literature of Inner Emigration. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-57113-909-2.

- Koehne, Samuel (2014). "Were the National Socialists a Völkisch Party? Paganism, Christianity, and the Nazi Christmas". Central European History. 47 (4): 760–790. doi:10.1017/S0008938914001897. hdl:11343/51140. ISSN 0008-9389. S2CID 146472475.

- Kroll, Joe Paul (2004). "Conservative at the Crossroads: 'Ironic' vs. 'Revolutionary' Conservatism in Thomas Mann's Reflections of a Non-Political Man". Journal of European Studies. 34 (3): 225–246. doi:10.1177/0047244104046382. ISSN 0047-2441. S2CID 153401527.

- Merlio, Gilbert (1992). "La Révolution conservatrice : contre-révolution ou révolution d'un nouveau type". In Gangl, Manfred; Roussel, Hélène (eds.). Les intellectuels et l'État sous la République de Weimar. Les Editions de la MSH. ISBN 978-2735105410.

- Merlio, Gilbert (2003). "Y a-t-il eu une " Révolution conservatrice " sous la République de Weimar ?". Revue Française d'Histoire des Idées Politiques. 1 (17): 123–141. doi:10.3917/rfhip.017.0123.

- Pfahl-Traughber, Armin (1998). Konservative Revolution und Neue Rechte: Rechtsextremistische Intellektuelle gegen den demokratischen Verfassungsstaat. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783322973900.

- Sieferle, Rolf Peter (1995). Die Konservative Revolution: Fünf biographische Skizzen (Paul Lensch, Werner Sombart, Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Hans Freyer). Fischer Taschenbuch-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-596-12817-4.

- Stern, Fritz (1961). The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology (1974 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520026261.

- Vinx, Lars (2010), "Carl Schmitt", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Weiß, Volker (2017). Die autoritäre Revolte: die Neue Rechte und der Untergang des Abendlandes. Klett-Cotta. ISBN 978-3-608-94907-0.<

- Woods, Roger (1996). The Conservative Revolution in the Weimar Republic. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-333-65014-X.