Eastern indigo snake

| Eastern indigo snake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Genus: | Drymarchon |

| Species: | D. couperi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Drymarchon couperi (Holbrook, 1842)

| |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

The eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon couperi) is a type of snake in the family Colubridae. It is native to the eastern United States. It is the longest native snake in the United States. It is the largest snake in the United States. It is also the largest, non-venomous snake in the southeastern United States.[3]

Description

[change | change source]The eastern indigo snake has a blue-black colour. It is the longest native snake species in the United States. Males usually grow up to 1.58 m (5.2 ft) in length. Females usually grow up to 1.38 m (4.5 ft) in length. Males usually weigh 2.2 kg (4.9 lb). Females usually weigh 1.5 kg (3.3 lb).[4]

Distribution and Habitat

[change | change source]The eastern indigo snake is found from southwestern South Carolina south through Florida and west to southern Alabama and southeastern Mississippi.[5]

The eastern indigo snake likes flatwoods, hammocks, dry glades, stream bottoms, sugarcane fields, riparian thickets, and sandy soils.[6]

The eastern indigo snake mostly lives in scrublands in Florida and Georgia with different types of plants. These are mainly longleaf pine, southern live oak, laurel oak, Chapman oak, and myrtle oak.[7]

Feeding

[change | change source]The Eastern indigo snake eats other snakes, turtles, lizards, frogs, toads, lots of small birds and mammals, and eggs.[6]

Reproduction

[change | change source]The Eastern indigo snake is oviparous. The breeding season is from November to April. Females lay their eggs from May to June. Females lay from 4 to 12 eggs. Young hatch in about 3 months, usually in August and September.[3]

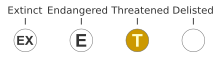

Conservation status

[change | change source]The eastern indigo snake is threatened by habitat loss. It is believed to be extinct in Alabama.[8][9]

The eastern indigo snake was extinct in northern Florida because of habitat loss and fragmentation. The eastern indigo snake was last seen in Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve in 1982, until 2017 when 12 snakes were released as part of a conservation program. 20 more snakes were released in 2018. 15 snakes in 2019.[10]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "Eastern indigo snake". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ↑ Species Drymarchon couperi at The Reptile Database . www.reptile-database.org.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gooch, Anika; Ranney, Meredith. "Drymarchon couperi (Eastern Indigo Snake)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ↑ Hyslop, Natalie L.; Cooper, Robert J.; Meyers, J. Michael (2009-09-03). "Seasonal Shifts in Shelter and Microhabitat Use of Drymarchon couperi (Eastern Indigo Snake) in Georgia". Copeia. 2009 (3): 458–464. doi:10.1643/CH-07-171. ISSN 0045-8511. S2CID 52462723.

- ↑ IUCN (2007-03-01). "Drymarchon couperi: Hammerson, G.A.: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2007: e.T63773A12714602". doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2007.rlts.t63773a12714602.en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Blair, W. Frank; Conant, Roger (1959). "A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern North America". AIBS Bulletin. 9 (1): 44. doi:10.2307/1292749. ISSN 0096-7645. JSTOR 1292749.

- ↑ Diemer, Joan E.; Speake, Dan W. (1983). "The Distribution of the Eastern Indigo Snake, Drymarchon corais couperi, in Georgia". Journal of Herpetology. 17 (3): 256. doi:10.2307/1563828. JSTOR 1563828.

- ↑ "Species Profile: Eastern Indigo Snake (Drymarchon couperi) | SREL Herpetology". srelherp.uga.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-05-30. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ↑ "Snakes in Alabama". 2012-05-27. Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ↑ "Good news for a big snake: 20 eastern indigo snakes just released to begin year two of the north Florida recovery". Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission. Retrieved 2020-09-16.