El Cajas National Park

| El Cajas National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

A lagoon in Cajas National Park | |

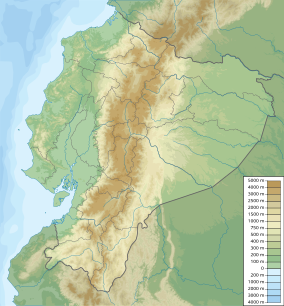

| Location | Ecuador Azuay Province |

| Nearest city | Cuenca |

| Coordinates | 02°50′46″S 79°13′13″W / 2.84611°S 79.22028°W |

| Area | 285.4 km2 (110.2 sq mi) |

| Established | November 5, 1996 (Resolution N° 057) |

| Official name | Parque Nacional Cajas |

| Designated | 14 August 2002 |

| Reference no. | 1203[1] |

El Cajas National Park or Cajas National Park (Spanish: Parque Nacional El Cajas) is a place high in the mountains in Ecuador. It is about 30 km west of Cuenca in Azuay. Part of the park, about 285.44 km2 (28,544 ha) between 3100m and 4450m above sea level, has páramo plants and sharp and steep hills and valleys. People made this place a National Park on November 5, 1996. The law that made it is called "resolution N° 057."

Name

[change | change source]The name "Cajas" comes from the Quichua word "cassa" meaning "gateway to the snowy mountains."[2] or "caxa" (Quichua:cold).[3] People also think the Spanish word "cajas" (boxes) may have something to do with the name.[3]

Geography and weather

[change | change source]The highest point is Cerro Arquitectos (Architects Hill). It is the 4,450 m high. The highest road is higher than 4,310 meters (13,550 feet) above sea level. The páramo has about 270 lakes and lagoons in it. Luspa is the largest lake. It is more than 78 hectares in size. The deepest part of the lake is 68 m down. Big walls of ice called glaciers made this lake. Glaciers also made U-shaped valleys and ravines in the park. Cajas has about 60% of the drinking water for the Cuenca area. Two of the four rivers of Cuenca come up out of the ground in Cajas: the Tomebamba and Yanuncay rivers. These rivers flow into the Amazon River. The Paute river also flows into the Amazon River. The park is right on top of the continental divide, so some of its rivers flow east and some flow west to the Pacific Ocean: the Balao and Cañar go to the Pacific ocean. The road crosses the continental divide at a pass called "Tres Cruces" (4,255 m) ("three crosses"). This is the very western part of the continental divide in South America.[2]

The park has average temperature of 13.2 °C and an average annual rain and other water of 1,072 mm each year. Clouds typically come up from the Pacific ocean and from the Paute river basin (near Cuenca) and put water into the air.

Living things

[change | change source]Plants

[change | change source]Because the park is so high about sea level and because there is so much water in the air, the living and dead things in the ground hold on to water. The high grassland has plants that live well in places like this. The most common plant is straw grass (Calamagrostis intermedia).

Above 3,300 meters, the park has "queñua" or "paper tree" (Polylepis) forest. A special plant called Fuchsia campii, in the family Onagraceae, might live in this forest. It is very rare. Scientists think it could live in this park because it also lives in another park nearby that also has high hills and water in the air.[4]

In the lower parts of the park, the cloud forest and high mountain forest grow. Most of these are in the ravines near the streams and rivers.

Animals

[change | change source]The Cajas National Park has many different animals, some of which could die out soon: The South American condor is one. There are only 80 of these condors in Ecuador. Others are the curiquinga, a large black and white bird that eats meat, and the largest hummingbird in the world, the giant hummingbird (Patagona gigas), which lives only on agave flowers[source?]. The violet-throated metaltail (Metalura gorjivioleta) lives in Cajas and other valleys nearby.[5] There are 157 bird species in the park. People like to come to the park to look at the birds.

People have found 44 different mammals in the park, for example, opossums, cats, and bats. Also, there are pumas, coatis, weasels, skunks, foxes, porcupines, pacas, shrews, rabbits, and other rodents, for example the Cajas water mouse (Chibchanomys orcesi) and Tate's shrew opossum (Caenolestes tatei).[2]

At least 17 amphibians live around the lagoons of Cajas, for example Atelopus, Telmatobius, Gastrotheca, Eleutherodactylus, and Colostethus. Because there are so many different amphibians, scientists think there must also be many different insects, because amphibians eat insects.

People in the park

[change | change source]Human beings lived in this place long ago, during the Cañari period in Ecuador's history. There were three long roads between Guapondelig (later Tomebamba, today Cuenca) to other places, for example Paredones, a big trading place. After the Incan people came to the area, they built more roads to go with the roads that were already there. People have found 28 good places to dig for human things in the park and nearby. The things they found in the ground show that people lived there before the Incas.[2] During the Colonial time, after Europeans came to Ecuador, people let animals eat grass here. But because it is a park now, people come here to hike, climb, camp, fish, and look at birds. Control points are located at the road entries to the park. The park has a special hut and can be reached from Cuenca and Guayaquil. A road from Chaucha to San Joaquin touches on the southern border of the park, and people can enter the park there.

International listings

[change | change source]Cajas is listed as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance. It is also an Important Bird Area. UNESCO is thinking about making it a World Natural Heritage Site.[2]

Related pages

[change | change source]References

[change | change source]- ↑ "Parque Nacional Cajas". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Parque National Cajas", map and brochure from Etapa, Cuenca, 2009

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cajas Park information

- ↑ Assessors: León-Yánez, S.; Pitman, N. / Evaluators: Valencia, R.; Pitman, N.; León-Yánez, S.; Jørgensen, P.M. (Ecuador Plants Red List Authority) (2004). "Fuchsia campii in IUCN 2009". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Vers. 2009.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Boris A. Tinoco; Pedro X. Astudillo; Steven C. Latta; Catherine H. Graham (2008). "Distribution, ecology and conservation of an endangered Andean hummingbird: the Violet-throated Metaltail" (PDF). Bird Conservation International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28.