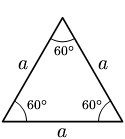

Equilateral triangle

In geometry, an equilateral triangle is a triangle where all three sides are the same length and all three angles are also the same and are each 60°. If an altitude is drawn, it bisects the side to which it is drawn, in turn leaving two separate 30-60-90 triangles

Other websites

[change | change source]- MathWorld - the construction of an equilateral triangle

Principal properties

[change | change source]

Denoting the common length of the sides of the equilateral triangle as a, we can determine using the Pythagorean theorem that:

- The area is

- The perimeter is

- The radius of the circumscribed circle is

- The radius of the inscribed circle is or

- The geometric center of the triangle is the center of the circumscribed and inscribed circles

- And the altitude (height) from any side is .

Denoting the radius of the circumscribed circle as R, we can determine using trigonometry that:

- The area of the triangle is

Many of these quantities have simple relationships to the altitude ("h") of each vertex from the opposite side:

- The area is

- The height of the center from each side, or apothem, is

- The radius of the circle circumscribing the three vertices is

- The radius of the inscribed circle is

In an equilateral triangle, the altitudes, the angle bisectors, the perpendicular bisectors and the medians to each side coincide.

Equal cevians

[change | change source]Three kinds of cevians are equal for (and only for) equilateral triangles:[1]

- The three altitudes have equal lengths.

- The three medians have equal lengths.

- The three angle bisectors have equal lengths.

Coincident triangle centers

[change | change source]Every triangle center of an equilateral triangle coincides with its centroid, which implies that the equilateral triangle is the only triangle with no Euler line connecting some of the centers. For some pairs of triangle centers, the fact that they coincide is enough to ensure that the triangle is equilateral. In particular:

- A triangle is equilateral if any two of the circumcenter, incenter, centroid, or orthocenter coincide.[2]: p.37

- It is also equilateral if its circumcenter coincides with the Nagel point, or if its incenter coincides with its nine-point center.[3]

Six triangles formed by partitioning by the medians

[change | change source]For any triangle, the three medians partition the triangle into six smaller triangles.

- A triangle is equilateral if and only if any three of the smaller triangles have either the same perimeter or the same inradius.[4]: Theorem 1

- A triangle is equilateral if and only if the circumcenters of any three of the smaller triangles have the same distance from the centroid.[4]: Corollary 7

Points in the plane

[change | change source]- A triangle is equilateral if and only if, for every point P in the plane, with distances p, q, and r to the triangle's sides and distances x, y, and z to its vertices,[5]: p.178, #235.4

References

[change | change source]- ↑ Owen, Byer; Felix, Lazebnik; Deirdre, Smeltzer (2010). Methods for Euclidean Geometry. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 36, 39.

- ↑ Yiu, Paul (1998). "Notes on Euclidean Geometry" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Andreescu, Titu; Andrica, Dorian (2006). Complex Numbers from A to...Z. Birkhäuser. pp. 70, 113–115.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cerin, Zvonko (2004). "The vertex-midpoint-centroid triangles" (PDF). Forum Geometricorum. 4: 97–109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- ↑ "Inequalities proposed in "Crux Mathematicorum"" (PDF).