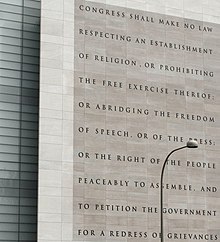

Freedom of speech in the United States

In the United States, freedom of speech and expression is strongly protected from government restrictions by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It is also protected by many state constitutions and state and federal laws. Freedom of speech, also called free speech, means the ability to publicly express opinions without interference or censorship from the government.[1][2][3][4] The term "freedom of speech" in the First Amendment refers to the right of the people to say what they want to say, and the right to not say what they do not want to say.[5] The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several types of speech that are not protected by the First Amendment. It has also recognized that governments may make reasonable restrictions on when, where, and how people speak. The First Amendment's constitutional right to free speech, which also applies to state and local governments under the incorporation doctrine,[6] prevents only government restrictions on speech, not restrictions imposed by private individuals or businesses, unless that individual or business is acting on behalf of the government.[7] However, some laws may restrict private businesses and individuals from restricting the speech of others, such as employment laws that stop employers from preventing employees from telling other employees what their salary is or trying to organize a labor union.[8]

The First Amendment's right to freedom of speech not only stops the government from making most restrictions on what people can say, but also protects the right to receive information,[9] stops the government from making restrictions that discriminate between speakers,[10] restricts the tort liability of individuals for certain speech,[11] and prevents the government from requiring individuals and corporations to say things that they do not agree with.[12][13][14]

Types of speech that are given less protection or not protected by the First Amendment include obscenity (as determined by the Miller test), fraud, child pornography, speech that is part of a crime,[15] speech that incites imminent lawless action, and regulation of commercial speech, such as advertising.[16][17] Within these areas, other limits on free speech balance the right to free speech and other rights. These rights include the rights of authors over their works (copyright), protection from violence against particular people, restrictions on the use of untruths to harm others (slander and libel), and restrictions on the speech of prisoners. When a speech restriction is challenged in court, it is assumed to be invalid and the government must convince the court that the restriction is valid.[18]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "freedom of speech In: The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition, 2020". Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ↑ "freedom of speech". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ↑ "free speech". Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 16, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ↑ "freedom of speech". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ↑ "Riley v. National Federation of the Blind, 487 U.S. 781 (1988), at 796 - 797". Justia US Supreme Court Center. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ↑ Sorrell v. IMS Health, Inc., 131 S. Ct. 2653, 2661 (Supreme Court of the United States 2011).

- ↑ Dunn, Christopher (April 28, 2009). "Column: Applying the Constitution to Private Actors (New York Law Journal)". New York Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ Berman-Gorvine, Martin (19 May 2014). "Employer Ability to Silence Employee Speech Narrowing in Private Sector, Attorneys Say". Bloomberg BNA. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ↑ Mart, Susan (2003). "The Right to Receive Information". Law Library Journal. 95 (2): 175–189. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ↑ Citizens United v. Federal Election Com'n, 130 S. Ct. 876, 896-897 (Supreme Court of the United States 2010).

- ↑ Snyder v. Phelps, 131 S. Ct. 1207 (Supreme Court of the United States 2011).

- ↑ Keighley, Jennifer (2012). "Can You Handle the Truth? Compelled Commercial Speech and the First Amendment". Journal of Constitutional Law. 15 (2): 544–550. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, 431 U.S. 209 (Supreme Court of the United States 1977).

- ↑ Riley v. National Federation of Blind of NC, Inc., 487 U.S. 781 (Supreme Court of the United States 1988).

- ↑ Volokh, Eugene (2016). "The 'Speech Integral to Criminal Conduct' Exception" (PDF). Cornell Law Review. 101: 981. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ United States v. Alvarez, 132 S. Ct. 2537 (Supreme Court of the United States 2012).

- ↑ Sorrell v. IMS Health, Inc., 131 S. Ct. 2653 (Supreme Court of the United States 2011).

- ↑ Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union, 542 U.S. 656, 660 (Supreme Court of the United States 2004).