Interstellar travel

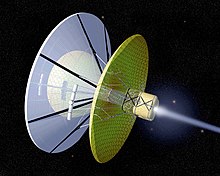

Interstellar space travel is manned or unmanned travel between stars. Interstellar travel is much more difficult than travel within the Solar System, though travel in starships is a staple of science fiction. Actually, there is no suitable technology at present.[1] However, the idea of a probe with an ion engine has been studied. The energy would come through a laser base station.[2]

Given sufficient travel time and engineering work, both unmanned and sleeper ship interstellar travel seem possible. Both present considerable technological and economic challenges which are unlikely to be met in the near future, particularly for manned probes. NASA, ESA and other space agencies have done research into these topics for several years, and have worked out some theoretical approaches.

Energy requirements appear to make interstellar travel impractical for "generation ships", but less so for heavily shielded sleeper ships.[3]

The difficulties of interstellar travel

[change | change source]The main challenge facing interstellar travel is the vast distances that have to be covered. This means that a very great speed and/or a very long travel time is needed. The travel time with most realistic propulsion methods would be from decades to millennia.

Hence an interstellar ship would be much more exposed to the hazards found in interplanetary travel, including vacuum, radiation, weightlessness, and micrometeoroids. At high speeds the vehicle would be penetrated by many microscopic particles of matter unless heavily shielded. Carrying the shield would greatly increase the propulsion problems.

Cosmic rays

[change | change source]Cosmic rays are of great interest because there is no protection outside the atmosphere and magnetic field. The energies of the most energetic ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) have been observed to approach 3 × 1020 eV,[4] about 40 million times the energy of particles accelerated by the Large Hadron Collider.[5] At 50 J,[6] the highest-energy ultra-high-energy cosmic rays have energies comparable to the kinetic energy of a 90-kilometre-per-hour (56 mph) baseball. As a result of these discoveries, there has been interest in investigating cosmic rays of even greater energies.[7] Most cosmic rays, however, do not have such extreme energies. The energy distribution of cosmic rays peaks at 0.3 gigaelectronvolts (4.8×10−11 J).[8]

Required energy

[change | change source]A significant factor is the energy needed for a reasonable travel time. A lower bound for the required energy is the kinetic energy K = ½ mv2 where m is the final mass. If deceleration on arrival is desired and cannot be achieved by any means other than the engines of the ship, then the required energy at least doubles, because the energy needed to halt the ship equals the energy needed to accelerate it to travel speed.

The velocity for a manned round trip of a few decades to even the nearest star is thousands of times greater than those of present space vehicles. This means that due to the v2 term in the kinetic energy formula, millions of times as much energy is required. Accelerating one ton to one-tenth of the speed of light requires at least 450 PJ or 4.5 ×1017 J or 125 billion kWh, not accounting for losses.

The source of energy has to be carried, since solar panels do not work far from the Sun and other stars. The magnitude of this energy may make interstellar travel impossible.[3] One engineer stated “At least 100 times the total energy output of the entire world [in a given year] would be required for the voyage (to Alpha Centauri)”.[3]

Interstellar medium

[change | change source]interstellar dust and gas may cause considerable damage to the craft, due to the high relative speeds and large kinetic energies involved. Larger objects (such as bigger dust grains) are far less common, but would be much more destructive. .

Travel time

[change | change source]The long travel times make it difficult to design manned missions. The fundamental limits of space-time present another challenge.[9] Also, interstellar trips would be hard to justify for economic reasons.

It can be argued that an interstellar mission which cannot be completed within 50 years should not be started at all. Instead, the resources should be invested in designing a better propulsion system. This is because a slow spacecraft would probably be passed by another mission sent later with more advanced propulsion.[10]

On the other hand, a case can therefore be made for starting a mission without delay, because the non-propulsion problems may turn out to be more difficult than the propulsion engineering.

Intergalactic travel involves distances about a million-fold greater than interstellar distances, making it radically more difficult than even interstellar travel.

Kennedy's calculation

[change | change source]Andrew Kennedy has shown that voyages undertaken before the minimum wait time will be overtaken by those who leave at the minimum, while those who leave after the minimum will never overtake those who left at the minimum.[11]

Kennedy's calculation depends on r, the mean annual increase in world power production. From any point in time to a given destination, there is a minimum to the total time to destination. Voyagers would probably arrive without being overtaken by later voyagers by waiting a time t before leaving. The relation between the time it takes to get to a destination (now, Tnow, or after waiting, Tt, and growth in velocity of travel is

Taking a journey to Barnard's Star, six light years away, as an example, Kennedy shows that with a world mean annual economic growth rate of 1.4% and a corresponding growth in the velocity of travel, the quickest human civilization might get to the star is in 1,110 years from the year 2007.

Interstellar distances

[change | change source]Astronomical distances are often measured in the time it would take a beam of light to travel between two points (see light-year). Light in a vacuum travels approximately 300,000 kilometers per second or 186,000 miles per second.

The distance from Earth to the Moon is 1.3 light-seconds. With current spacecraft propulsion technologies, a craft can cover the distance from the Earth to the Moon in around eight hours (New Horizons). That means light travels approximately thirty thousand times faster than current spacecraft propulsion technologies. The distance from Earth to other planets in the Solar System ranges from three light-minutes to about four light-hours. Depending on the planet and its alignment to Earth, for a typical unmanned spacecraft these trips will take from a few months to a little over a decade. The distance to other stars is much greater. If the distance from Earth to Sun is scaled down to one meter, the distance to Alpha Centauri A would be 271 kilometers or about 169 miles.

The nearest known star to the Sun is Proxima Centauri, which is 4.23 light-years away. The fastest outward-bound spacecraft yet sent, Voyager 1, has covered 1/600th of a light-year in 30 years and is currently moving at 1/18,000th the speed of light. At this rate, a journey to Proxima Centauri would take 72,000 years. Of course, this mission was not specifically intended to travel fast to the stars, and current technology could do much better. The travel time could be reduced to a few millennia using solar sails, or to a century or less using nuclear pulse propulsion.

Special relativity offers the possibility of shortening the travel time: if a starship with sufficiently advanced engines could reach velocities near the speed of light, relativistic time dilation would make the voyage much shorter for the traveller. However, it would still take many years of elapsed time as viewed by the people remaining on Earth. On returning to Earth, the travellers would find that far more time had elapsed on Earth than had for them (twin paradox).

Many problems would be solved if wormholes existed. General relativity does not rule them out, but so far as we know at present, they do not exist.

Communications

[change | change source]The round-trip delay time is the minimum time between a probe signal reaching Earth, and the probe getting instructions from Earth. Given that information can travel no faster than the speed of light, this is for the Voyager 1 about 32 hours, near Proxima Centauri it would be 8 years. Faster reactions would have to be programmed to be carried out automatically. Of course, in the case of a manned flight the crew can respond immediately to their observations. However, the round-trip delay time makes them not only extremely distant but, in terms of communication, extremely isolated from Earth. Another factor is the energy needed for interstellar communications to arrive reliably. Obviously, gas and particles would degrade signals (interstellar extinction), and there would be limits to the energy available to send the signal.

Manned missions

[change | change source]The mass of any craft capable of carrying humans would inevitably be substantially larger than that necessary for an unmanned interstellar probe. The vastly greater travel times involved would require a life support system. The first interstellar missions are unlikely to carry life forms.

Prime targets for interstellar travel

[change | change source]There are 59 known stellar systems within 20 light years from the Sun, containing 81 visible stars. The following could be considered prime targets for interstellar missions:[12] Radiation dangers would rule out any organic beings for an expedition to Sirius. In any event, it is hard to visualise any manned expeditions at all, given the probable journey times.

Perhaps the most likely time for interstellar travel would be when a star comes through our Oort cloud. We should get a good 10,000 years' warning of this, so could plan for the event in some detail. See Scholz's star for the last time one came through.

| Stellar system | Distance (ly) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha Centauri | 4.3 | Closest system. Three stars (G2, K1, M5). Component A is similar to the Sun (a G2 star). Alpha Centauri B has one confirmed planet.[13] |

| Barnard's Star | 6.0 | Small, low luminosity M5 red dwarf. Next closest to Solar System. |

| Sirius | 8.7 | Large, very bright A1 star with a white dwarf companion. |

| Epsilon Eridani | 10.8 | Single K2 star slightly smaller and colder than the Sun. Has two asteroid belts, might have a giant and one much smaller planet,[14] and may possess a solar system type planetary system. |

| Tau Ceti | 11.8 | Single G8 star similar to the Sun. High probability of possessing a solar-system-type planetary system: current evidence shows 5 planets with potentially two in the habitable zone. |

| Gliese 581 | 20.3 | Multiple planet system. The unconfirmed exoplanet Gliese 581 g and the confirmed exoplanet Gliese 581 d are in the star's habitable zone. |

| Vega | 25.0 | At least one planet, and of a suitable age to have evolved primitive life [15] |

Existing and near-term astronomical technology is capable of finding planetary systems around these objects, increasing their potential for exploration.

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "Project Daedalus - Origins". 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-26.

- ↑ "Лендис. Межзвездный ионный зонд, снабжаемый энергией по лазерному лучу". go2starss.narod.ru.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 O’Neill, Ian (2008). "Interstellar travel may remain in science fiction". Universe Today.

- ↑ Nerlich, Steve (12 June 2011). "Astronomy without a telescope – Oh-My-God particles". Universe Today. Universe Today. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ "Facts and figures". The LHC. European Organization for Nuclear Research. 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Gaensler, Brian (November 2011). "Extreme speed". COSMOS (41). Archived from the original on 2013-04-07. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ↑ L. Anchordoqui et al 2003. (2003). "Ultrahigh energy cosmic rays: the state of the art before the Auger Observatory". International Journal of Modern Physics A. 18 (13): 2229–2366. arXiv:hep-ph/0206072. Bibcode:2003IJMPA..18.2229A. doi:10.1142/S0217751X03013879. S2CID 119407673.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Nave, Carl R. "Cosmic rays". HyperPhysics Concepts. Georgia State University. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ Lance Williams (2012). "Electromagnetic control of spacetime and gravity: the hard problem of interstellar travel". Astronomical Review. 7 (2): 5. Bibcode:2012AstRv...7b...5W. doi:10.1080/21672857.2012.11519699. S2CID 125078631. Archived from the original on 2013-01-17. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ↑ Kondo, Yoji: Interstellar travel and multi-generation spaceships, ISBN 1-896522-99-8 p. 31

- ↑ Kennedy, Andrew (2006). "Interstellar travel: the wait calculation and the incentive trap of progress". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society (JBIS). 59 (7): 239–246. Bibcode:2006JBIS...59..239K. Archived from the original on 2018-09-27. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ↑ Forward, Robert L. (1996). "Ad Astra!". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society (JBIS). 49 (1): 23–32.

- ↑ jobs (October 2012). "The exoplanet next door : Nature News & Comment". Nature. 490 (7420). Nature.com: 207–211. doi:10.1038/nature11572. PMID 23075844. S2CID 1110271. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ↑ Star: eps Eridani. Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia (Die Enzyklopädie der extrasolaren Planeten), retrieved 2011-01-15

- ↑ "ScienceShot: Older Vega Mature Enough to Nurture Life - ScienceNOW". Archived from the original on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2013-04-09.