Jihadism

"Jihadism" (also "jihadist movement", "jihadi movement" and variants) is a 21st-century neologism found in Western languages to describe Islamist militant movements seen by the military to be "rooted in Islam" and a threat to the West.[5]

The term "jihadism" has been used since the 1990s. [6] It was first used by Indian and Pakistani media, as well as French scholars, who used the more precise term "Salafi jihadism (or jihadist Salafism) ". French political scientist and orientalist Gilles Kepel identified a special Salafist form of jihadism in the 1990s. [7] Western journalists adopted it in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks of 2001.[8]

A distinction is made between Salafi jihadism and Deobandi jihadism. [9] [10] Salafi jihadist organizations include [11]: Salafia Jihadia, Al-Qaeda, ISIS, Salafi Group for Preaching and Jihad, Boko Haram, Al-Shabab, Hizbut Tahrir, Salafi Army of Abu Bakr, Salafi Army of Jaish al-Umma, Caucasus Emirate, Dawa FFM, Die Wahre Religion, Moroccan Fighting Group and others. Although the Taliban are Deobandi and not Salafi, they have worked closely with Salafi Osama bin Laden and various Salafi jihadist leaders. [12]

Terminology

[change | change source]The concept of jihad ('to strive'/'to strive') is fundamental in Islam and has many applications: the greater jihad (inner jihad) means the internal struggle against evil within oneself, while the lesser jihad (outer jihad) is divided into the jihad of the pen/tongue (debate or admonition) and the jihad of the sword. Modern Muslim scholars generally equate military jihad with defensive warfare. [13] [14] Most modern Muslim opinion holds that internal jihad takes precedence over external jihad in the Islamic tradition, while many Western authors hold the opposite view. [15] To justify their terrorist acts, jihadists resort to fatwas developed by jihadist-Salafist legal authorities whose legal works are distributed via the Internet. [16]

History

[change | change source]Some observers [17] [18] have noted a change in the rules of jihadism - from the original "classical" doctrine to the Salafi jihadism of the 21st century. [19] According to histrorian Sadrat Qadri, [17] over the last couple of centuries, gradual changes in Islamic legal doctrine (developed by Salafis who condemned any innovation (bid'ah) in religion) have "normalized" what was once "unthinkable". [17]

Salafism and Salafi jihadism(1990 - present)

[change | change source]Some of the early Islamic scholars and theologians who have had a profound influence on terrorism and the ideology of modern jihadism include the medieval Salafi thinkers Ibn Taymiyyah and Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, along with modern Salafi ideologists Muhammad Rashid Rida, Sayyid Qutb, and Abul Ala Mawdudi. [20] [21] [22]

The term "jihadism" (formerly "Salafi jihadism" ) emerged in the 2000s to describe contemporary jihadist movements whose development can be traced in retrospect to the development of Salafism, coupled with the emergence of al-Qaeda.

Salafi jihadism

[change | change source]Salafism is a movement in Sunni Islam that unites Muslim religious figures who, at different periods, have called for a focus on the way of life of the righteous ancestors (salaf salihin ), qualifying as “ bid’ah ” all the latest innovations in the indicated areas, starting with methods of symbolic- allegorical interpretation of the Koran and ending with all sorts of innovations brought to the Muslim world by its contacts with the West. [23]

Salafis include, for example, Ibn Taymiyyah, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab and the ideologists of the Muslim Brotherhood association. [23]

According to the German Federal Agency for Civic Education, almost all terrorists are "Salafis", but not all Salafis are terrorists. The call for the establishment of a religious state in the form of a caliphate means that Salafis reject the rule of law and the sovereignty of people's power. [24]

British writer Shiraz Maher, author of Salafi Jihadism: The History of an Idea, traces the origins of this particular movement to Ibn Taymiyyah and the 18th-century theologian Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. [25]

In Western literature, the terms “ fundamentalism ”, and “ Wahhabism ” are used to characterize the Salafi ideology. [23] They are also called "Muslim Puritans". [26] [27]

Ideologists of Salafi jihadism

[change | change source]The ideologists of Salafi jihadism were Arab veterans of the Afghan jihad: Abu Qatada al-Filistini, the Syrian Abu Musab, Abu Hamza al-Masri, and others. [28] [29] Mohammed Yusuf, founder of the Nigerian Salafi group Boko Haram; [30] Omar Bakri Muhammad, [31] Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of ISIS [32] [33] and others are also adherents of Salafism .

Osama bin Laden

[change | change source]The most famous leader of the Salafi jihadists was Osama bin Laden. [34] [35] Saudi dissident preachers Salman al-Awda and Safar al-Hawali were highly respected at the school. Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri praised Sayyid Qutb, stating that Qutb's call became the ideological inspiration for the modern Salafi-jihadist movement. [36]

A step towards the beginning of global “ Salafi jihadism ” was the announcement on August 8, 1996 by Osama bin Laden of “War against the Americans who have occupied the land of the Two Holy Mosques ”. [37]

Other leading figures in the Salafi-jihadist movement include Anwar al-Awlaki, the former leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) ; [38] Abu Bakar Bashir, the leader of the banned Indonesian militant group ( Jemaah Islamiyah ); Nasir al-Fahd, a Saudi Arabian Salafi-jihadist scholar who opposes the Saudi state and has reportedly pledged allegiance to ISIS . Some Salafi theologians have condemned the doctrines of Salafi jihadism as bid'ah ("innovation") and "heresy". [39]

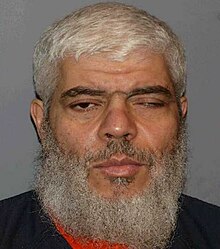

Abu Hamza al-Masri

[change | change source]

Abu Hamza al-Masri is a radical Salafi jihadist [42] and terrorist . In 1979 he left for Great Britain . In 1987 he performed the Hajj, during which he met the founder of the Afghan Mujahideen movement, Abdullah Azzam .

In 2012, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg allowed the extradition of al-Masri and four other people accused of terrorism to the United States. [43] Abu Hamza al-Masri was extradited to the United States on October 5, 2012. [44]

During the trial on 7 May 2014, it emerged [45] that Abu Hamza al Masri worked for the British counterintelligence agency MI5.

In January 2015, it became known that Abu Hamza was sentenced to life imprisonment. [46]

Al-Baghdadi

[change | change source]Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is a Salafi jihadist [47] [48] and leader of the Salafi group ISIS [47] [48]

Other Salafi ideologists

[change | change source]Other leading figures in the Salafi-jihadist movement include Anwar al-Awlaki, the former leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP); [49] Abu Bakar Bashir, the leader of the banned Indonesian militant group ( Jemaah Islamiyah ); Nasir al-Fahd, a Saudi Arabian Salafi-jihadist scholar who opposes the Saudi state and has reportedly pledged allegiance to ISIS .

Increase in the number of Salafi terrorist attacks

[change | change source]According to Bruce Livesey, by 2005 Salafi terrorists were spreading their influence in Europe, having attempted more than 30 terrorist attacks in EU countries from September 2001 to early 2005. [50]

Salafi Jihadist Organizations

[change | change source]

" Salafi" jihadist groups include al-Qaeda [51] [52], the now-defunct Algerian Armed Islamic Group (GIA) [53] and the Egyptian group al-Gama'a al-Islamiya.

During the Algerian Civil War of 1992–98, the GIA was one of two main Salafist armed groups (the other being the Army of Islamic Salvation, or AIS) fighting the Algerian army and security forces. The remnants of the GIA continued their activities as the "Salafi Group for Preaching and Combat", which since 2015 has called itself "Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb". [54]

Salafia Jihadia

[change | change source]Salafia Jihadia is a Salafi terrorist organization that was active in Morocco and Spain . Had links to al-Qaeda and the Moroccan Islamic Fighting Group . The Salafi terrorist group became widely known after the 2003 Casablanca attacks, when 12 suicide bombers killed 33 people and wounded 100.

Al Qaeda

[change | change source]Perhaps the most famous and effective Salafi jihadist group was al-Qaeda. [55] Al-Qaeda evolved from Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), or the "Office of Services," a Muslim organization founded in 1984 to raise and distribute funds and recruit foreign mujahideen for the war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. It was founded in Peshawar, Pakistan, by Osama bin Laden and Abdullah Yousuf Azzam . When it became apparent that jihad had forced the Soviet military to abandon its mission in Afghanistan, some mujahideen called for expanding their operations to include fighting terrorists in other parts of the world, and on August 11, 1988, al-Qaeda was formed by bin Laden. [56] [57] Members were required to take a vow ( bayat ) to follow their leaders. [58] Al-Qaeda emphasized jihad against the "distant enemy," by which it meant the United States. In 1996, it declared a jihad to expel foreign forces and interests from territories it considered Islamic. The largest terrorist operation is considered to be the September 11 attacks against the United States. [59]

Boko Haram

[change | change source]Boko Haram in Nigeria is a Salafi jihadist group [60] that has killed tens of thousands of people and forced 2.3 million people to flee their homes. [61]

According to Mohammed M. Hafez, "as of 2006, the two main groups in the Salafi jihadist camp" in Iraq were the Mujahideen Shura Council and the Ansar al-Sunna group. [62] There are also a number of small jihadist Salafi groups operating in Azerbaijan. [63]

Deobandi jihadism

[change | change source]Deobandi jihadism is a militant interpretation of Islam that draws on the teachings of the Deobandi movement that originated in the Indian subcontinent in the 19th century. The Deobandi movement has experienced 3 waves of jihadism. The first wave involved the establishment of an Islamic precinct centred at Thana Bhawan by elders of the movement during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, prior to the founding of Darul Uloom Deoband . Imdadullah Muhajir Makki was the Amir al-Mu'minin of this territory. However, after the British defeated the Deoband forces at the Battle of Shamli, the territory fell. After the establishment of Darul Uloom Deoband, Mahmud Hasan Deobandi led the initiation of the second wave. He mobilized armed resistance against the British through various initiatives, including the formation of the Samratut Tarbiat. When the British discovered his " Silk Letter Movement ", they arrested him and held him captive in Malta . After his release, he and his students became active in politics and took an active part in the democratic process. In late 1979, the Pakistan-Afghan border became the focus of the third wave of the Deobandi jihadist movement, fueled by the Soviet-Afghan War . Under the patronage of President Zia-ul-Haq (who was himself a Deobandi ), its expansion took place through various Deobandi madrassas such as Darul Uloom Haqqania and Jamia Uloom-ul-Islamia. Trained militants from the Pakistan-Afghan border participated in the Afghan jihad and later formed various Deobandi terrorist organizations, including the Taliban . The most successful example of Deobandi jihadism is the Taliban movement, which established Sharia law in Afghanistan. The head of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, Sami-ul-Haq, is called the "father of the Taliban". [64] [65]

Deobandi and terrorism

[change | change source]Mahmud Hasan Deobandi, the first student of Darul Uloom Deoband, later became its headmaster and actively incited armed rebellion through his students. Having been appointed as a teacher at Darul Uloom Deoband, he founded Samratut Tarbiat in 1878. [66] In Pakistan, the majority of the population follows the Deobandi sect, as a result of which most of the madrassas have joined this sect. [67]

The Deobandi terrorist organization " Taliban " was formed in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s. The founder of the Taliban movement was Mullah Omar, a former mujahideen who lost an eye during the war with the Soviet Union. In 1994, he gathered a group of students and religious scholars, many of whom had been educated in Deobandi madrassas located in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, and founded the Taliban as a militant Deobandi movement. [68]

See also

[change | change source]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ El-Baghdadi, Iyad. "Salafis, Jihadis, Takfiris: Demystifying Militant Islamism in Syria". 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- ↑ Trevor Stanley. "The Evolution of Al-Qaeda: Osama bin Laden and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi". Archived from the original on 2022-01-03. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ↑ Jones, Seth G. (2014). A Persistent Threat: The Evolution of al Qa'ida and Other Salafi Jihadists (PDF). Rand Corporation.

- ↑ "The Global Salafi Jihad". the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. 2003-07-09. Archived from the original on 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ↑ Compare: Hammer, Olav; Rothstein, Mikael, eds. (2012). "16". The Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements. Cambridge University Press. p. 263. ISBN 9781107493551. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

'Jihadism' is a term that has been constructed in Western languages to describe militant Islamic movements that are perceived as existentially threatening to the West. Western media have tended to refer to Jihadism as a military movement rooted in political Islam.

- ↑ "What is jihadism?". BBC News. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles (2021). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (5th ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 219–222. ISBN 9781350148598.

- ↑ Natana DeLong-Bas (2009). "Jihad". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2016-06-29. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara D. (2002). 'Traditionalist' Islamic activism: Deoband, Tablighis, and Talibs. Leiden: ISIM. p. 13. ISBN 90-804604-6-X. OCLC 67024546.

- ↑ Hashmi, Arshi Saleem. The Deobandi Madrassas in India and their elusion of Jihadi Politics: Lessons for Pakistan (PhD thesis). Quaid-i-Azam University.

- ↑ Jones, Seth G. (2014). A Persistent Threat: The Evolution of al Qa'ida and Other Salafi Jihadists (PDF). Rand Corporation. p. 2.

- ↑ Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2002) pp.219-222

- ↑ Peters, Rudolph (2015). "The Doctrine of Jihad in Modern Islam". Islam and Colonialism: The Doctrine of Jihad in Modern History. Vol. 20. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. p. 105–124. doi:10.1515/9783110824858.105. ISBN 9783110824858. ISSN 1437-5370.

- ↑ Wael B. Hallaq (2009). Sharī'a: Theory, Practice, Transformations. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 334–338.

- ↑ Bonner 2006.

- ↑ French, Nathan S. (2020). "A Jihadi-Salafi Legal Tradition? Debating Authority and Martyrdom". And God Knows the Martyrs: Martyrdom and Violence in Jihadi-Salafism. Oxford and New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 36–69. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190092153.003.0002. ISBN 9780190092153.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kadri, Sadakat (2012). Heaven on Earth: A Journey Through Shari'a Law from the Deserts of Ancient Arabia. London: Macmillan Publishers. p. 172–175. ISBN 978-0099523277.

- ↑ Gorka, Sebastian (3 October 2009). "Understanding History's Seven Stages of Jihad". Combating Terrorism Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ↑ Ajjoub, Orwa (2021). The Development of the Theological and Political Aspects of Jihadi-Salafism (PDF). Lund: Swedish South Asian Studies Network (SASNET) at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University. p. 1–28. ISBN 978-91-7895-772-9.

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (2009). "Islam Subverted? Jihad as Terrorism". Partisans of Allah: Jihad in South Asia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 239–301. doi:10.4159/9780674039070-007. ISBN 9780674039070.

- ↑ R. Habeck, Mary (2006). Knowing the Enemy: Jihadist Ideology and the War on Terror. London: Yale University Press. p. 17–18. ISBN 0-300-11306-4.

- ↑ Haniff Hassan, Muhammad (2014). The Father of Jihad. 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE: Imperial College Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-78326-287-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Ибрагим, Сагадеев 1991.

- ↑ Pfahl-Traughber, Prof Dr Armin (2015-09-09). "Salafismus – was ist das überhaupt? | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- ↑ Holland, Tom (23 June 2016). "How Islamic is Islamic State? Shiraz Maher's new book investigates". The New Statesman. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ↑ Williams, Wes (2013-01-18). Religion and Rights: The Oxford Amnesty Lectures. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-84779-502-1. Archived from the original on 2017-01-01. Retrieved 2017-01-01.

- ↑ Knysh, Alexander (2015-09-30). Islam in Historical Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34712-5. Archived from the original on 2017-01-01. Retrieved 2017-01-01.

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, 2002, p.220

- ↑ «Jihadist-Salafism» is introduced by Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 220

- ↑ Dowd, Robert A. (1 July 2015). Christianity, Islam, and Liberal Democracy: Lessons from Sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780190225216.

- ↑ Moghadam, Assaf (1 May 2011). The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of Suicide Attacks. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9781421401447.

Salafi Jihadist preachers such as Abu Hamza al-Masri and Omar Bakri Muhammad help inspire thousands of Muslim youth to develop a cultlike relationship to martyrdom in mosques

- ↑ "Who was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi?", BBC News, 2019-10-27

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/11/12/what-radicalized-abu-bakr-al-baghdadi/

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ El-Baghdadi, Iyad. "Salafis, Jihadis, Takfiris: Demystifying Militant Islamism in Syria". 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- ↑ Farid Shapoo, Sajid (2017-07-19). "Salafi Jihadism – An Ideological Misnomer". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 2021-08-19.

- ↑ al-Saleh, Huda (2018-03-21). "After Saudi Crown Prince's pledge to eliminate Brotherhood, Zawahri defends them". AlArabiya News. Archived from the original on 2021-03-31.

- ↑ Template:Статья

- ↑ Richey, Warren. "To turn tables on ISIS at home, start asking unsettling questions, expert says". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ Farid Shapoo, Sajid (2017-07-19). "Salafi Jihadism – An Ideological Misnomer". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 2021-08-19.

Another interesting aspect of Salafi Jihadism is that the traditional Salafi scholars debunk it as a Salafi hybrid and that it is far removed from the traditional Salafism.

- ↑ "The Global Salafi Jihad". the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. 2003-07-09. Archived from the original on 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, 2002, p.220

- ↑ al-Saleh Huda (2018). After Saudi Crown Prince’s pledge to eliminate Brotherhood, Zawahri defends them Archive copy at the Internet Archive // Al Arabiya Englsh

- ↑ Лондон скоро выдаст США исламиста Абу Хамзу Archive copy at the Internet Archive // Би-би-си, 24 сентября 2012

- ↑ "Радикальный британский исламист экстрадирован в США". Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- ↑ "Abu Hamza 'secretly worked for MI5' to 'keep streets of London safe' (англ.)". 2014-05-07. Archived from the original on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ↑ "Радикальный имам Абу Хамза приговорён к пожизненному сроку". 2015-01-09. Archived from the original on 2015-01-10. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "Who was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi?", BBC News, 2019-10-27

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/11/12/what-radicalized-abu-bakr-al-baghdadi/

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Richey, Warren. "To turn tables on ISIS at home, start asking unsettling questions, expert says". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Salafist movement by Bruce Livesey". PBS Frontline. 2005. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2014-10-24.

- ↑ El-Baghdadi, Iyad. "Salafis, Jihadis, Takfiris: Demystifying Militant Islamism in Syria". 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- ↑ Template:Статья

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad By Gilles Kepel, Anthony F. Roberts. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 9781845112578.

- ↑ "Islamism, Violence and Reform in Algeria: Turning the Page (Islamism in North Africa III)]". International Crisis Group Report. 2004-07-30. Archived from the original on 2015-05-27. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- ↑ Jones, Seth G. (2014). A Persistent Threat: The Evolution of al Qa'ida and Other Salafi Jihadists (PDF). Rand Corporation.

- ↑ Wander, Andrew (July 13, 2008). "A history of terror: Al-Qaeda 1988–2008". The Guardian, The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

11 August 1988 Al-Qaeda is formed at a meeting attended by Bin Laden, Zawahiri and Dr Fadl in Peshawar, Pakistan.

- ↑ "The Osama bin Laden I know". 2006-01-18. Archived from the original on 2007-01-01. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ↑ Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf. p. 133–34. ISBN 0-375-41486-X.

- ↑ "The Global Salafi Jihad". the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. 2003-07-09. Archived from the original on 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ↑ Thurston, Alexander (2019). Search Results Boko Haram: The History of an African Jihadist Movement. Princeton University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780691197081.

- ↑ "Nigeria's Boko Haram Kills 49 in Suicide Bombings". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-21.

- ↑ Hafez, Mohammed M. (2007). Suicide Bombers in Iraq By Mohammed M. Hafez. US Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 9781601270047.

- ↑ The Two Faces of Salafism in Azerbaijan Archived 2010-12-26 at the Wayback Machine. Terrorism Focus Volume: 4 Issue: 40, December 7, 2007, by: Anar Valiyev

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara D. (2002). 'Traditionalist' Islamic activism: Deoband, Tablighis, and Talibs. Leiden: ISIM. p. 13. ISBN 90-804604-6-X. OCLC 67024546.

- ↑ Hashmi, Arshi Saleem. The Deobandi Madrassas in India and their elusion of Jihadi Politics: Lessons for Pakistan (PhD thesis). Quaid-i-Azam University.

- ↑ Shamsuzzaman 2019.

- ↑ Hashmi, Arshi Saleem. The Deobandi Madrassas in India and their elusion of Jihadi Politics: Lessons for Pakistan (PhD thesis). Quaid-i-Azam University.

- ↑ Источник (Thesis).