Michelangelo

Michelangelo | |

|---|---|

Chalk portrait of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra | |

| Born | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni 6 March 1475 Caprese, Tuscany |

| Died | 18 February 1564 (aged 88) Rome |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Apprentice to Ghirlandaio[1] |

| Known for | sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry |

| Notable work | David, The Creation of Adam, Pieta |

| Movement | High Renaissance |

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni[1] (6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564),[2] known as Michelangelo, was an Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, poet, and engineer. Along with Leonardo da Vinci, he is often called a "Renaissance Man" which means that he had great talent in many areas.

Michelangelo lived an extremely busy life, creating a great number of artworks. Some of Michelangelo's works are among the most famous that have ever been made. They include two very famous marble statues, the Pieta in Saint Peter's Basilica and David which once stood in a plazza in Florence but is now in the Accademia Gallery. His most famous paintings are huge frescos, the Sistine Chapel Ceiling and the Last Judgement. His most famous work of architecture is the east end and dome of Saint Peter's Basilica.

A lot is known about Michelangelo's life because he left many letters, poems and journals. Because he was so famous, he became the very first artist to have his biography (story of his life) published while he was still living.[3] His biographer, Giorgio Vasari, said that he was the greatest artist of the Renaissance. He was sometimes called Il Divino ("the divine one").[4] Other artists said that he had terribilità, (his works were so grand and full of strong emotion that they were scary). Many other artists who saw his work tried to have the same emotional quality. From this idea of terribilità came a style of art called Mannerism.

Biography

[change | change source]Childhood

[change | change source]Michelangelo was born on 6 March 1475 in Caprese near Arezzo, Tuscany.[5] His father was Lodovico di Leonardo di Buonarroti di Simoni, and his mother was Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena.[6] The Buonarrottis were a banking family from Florence. They claimed they were descended from the noble Countess Matilda of Canossa. Michelangelo's father had lost most of the bank’s money, so he worked for the local government in the town of Chiusi. When Michelangelo was a baby, the family moved back to Florence. As he was sickly, Michelangelo was sent to live on a small farm with a stonecutter and his wife and family.[6] The stonecutter worked at a marble quarry owned by Michelangelo's father. Many years later Michelangelo said that the two things that had helped him to be a good artist were being born in the gentle countryside of Arezzo and being raised in a house where, along with his nurse's milk, he was given the training to use a chisel and hammer.[5] His mother died when he was only six.

Michelangelo’s father then brought him back to Florence and sent him to study with a tutor, Francesco da Urbino.[5][7] Michelangelo was not interested in his school lessons. He explored the great churches of the city and drew copies of the frescos that he saw there.[7] When he was thirteen, he was apprenticed to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.[1][8] Ghirlandaio had a large busy studio. He had rich patrons who worked for the Medici. He painted frescos in their family chapels. Michelangelo was able to learn the art of fresco painting very well, from Ghirlandaio. In a large workshop such as Ghirlandaio’s, artists would have been working in all sorts of different media, including sculpture, metalwork and painting altarpieces. Michelangelo would have learned about all these things. When Michelangelo was only fourteen, his father persuaded Ghirlandaio to pay his apprentice as an artist, which was highly unusual at the time.[9]

Working for the Medici

[change | change source]The richest, most powerful family in Florence were the Medici. They had an academy where some of the most famous philosophers, poets, and artists met to share their ideas. The Medici family were important patrons of the arts. In 1489, Lorenzo de' Medici, the head of the family, asked Ghirlandaio to send his two best pupils to the academy.[10] Michelangelo was one of the students chosen and he attended the academy from 1490 to 1492. He heard the teaching and discussion of Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola and Angelo Poliziano.[11] The philosophy that they taught was called Humanism. It was based on the philosophy of the ancient Greek Plato. Michelangelo’s ideas and his art were influenced by these teachings.

Michelangelo and another young sculptor called Pietro Torrigiano studied sculpture under Bertoldo di Giovanni. Michelangelo had an argument with Torrigiano, who punched him on the nose so that it was badly broken and spoilt his appearance for the rest of his life.[12] Michelangelo sculpted some reliefs (flat panels with raised figures on them). One was ‘’the Battle of the Centaurs’’ which was made for Lorenzo de Medici.[13]

In 1492, Michelangelo’s patron, Lorenzo de' Medici died. This brought about a big change in Michelangelo’s life.[14] He went back to live at his father’s house. Michelangelo asked the prior at the Church of Santo Spirito to allow him to study the anatomy of the bodies of people who had died at the church’s hospital. In 1493, as a “thank-you” gift to the prior, Michelangelo carved a large wooden Crucifix which still hangs in the church.[15] In January 1494, there were very heavy snowfalls. Lorenzo de’ Medici’s son, Piero de Medici commissioned Michelangelo to make a snow statue. So Michelangelo began to work for the Medici again.

In 1494, a new leader rose up in Florence. He was a Dominican friar called Savonarola. His strong preaching caused people to burn their books, throw away their jewellery and chase the rich families out of the city. The Medici had to go. For Michelangelo, it was a good time to travel. He stayed for a while in Venice, then moved to Bologna. In Bologna he soon got work sculpting three figures for the big marble Shrine of Saint Dominic.[14] When things calmed down in Florence, Michelangelo returned and worked for another member of the Medici family, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici.[16]

Michelangelo made a marble statue of Cupid asleep. Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco told Michelangelo that it looked just like a real Ancient Roman statue and said that if he made it dirty and knocked a few chips off, someone would pay a lot of money for it. Lorenzo sold it to a Cardinal who discovered that it was a fraud.[17] He thought that Michelangelo’s work was so good that he told the pope about it. The pope then invited Michelangelo to go to Rome and work for him.[16]

Rome

[change | change source]

Michelangelo arrived in Rome 25 June 1496 at the age of 21.[18] He lived near the Church of Santa Maria di Loreto on the Gianicolo hill.

In 1496 he got an important “commission” (he was given a paid job) from Cardinal Raffaele Riario. The Cardinal wanted Michelangelo to make a marble statue, larger than life-size, of Bacchus, the Ancient Roman God of wine. Michelangelo worked hard at the statue. He carved Bacchus as a young man who was quite drunk and looked as if he was staggering as he raised his cup to make a toast. The cardinal did not like the drunken Bacchus and would not pay for it. A banker called Jacopo Galli bought it for his garden.

Michelangelo’s next important commission was from the French Ambassador who asked him to make a statue of the Virgin Mary mourning over the dead body of her son Jesus. This type of artwork, either a painting or a statue, is called by the Italian name “Pieta” (say: “Pe-ay-ta”). Michelangelo’s Pieta is the most famous Pieta that has ever been made. It is now in Saint Peter's Basilica and is visited by thousands of people every day. Giorgio Vasari wrote: "It is a miracle that a shapeless block of stone could have been carved away to make something so perfect that even nature could hardly have made it better, using real human flesh."

Works

[change | change source]

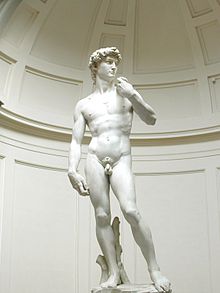

Statue of David

[change | change source]In 1499 Michelangelo returned to Florence. The priest Savonarola had made so many people angry that he had been put to death in 1498. Life in Florence started to return to normal. Many years earlier the Guild of Woolworkers had commissioned some artists to make statues of the heroes of the city. A sculptor called Agostino di Duccio had started carving a huge statue of David, the hero of the Bible story of David and Goliath. For 40 years the Guild of Woolworkers owned the huge block of marble, with the statue hardly begun. In 1501 they commissioned the young Michelangelo to carve it. It took him three years to complete.

Once again Michelangelo made a statue that became world-famous. The statue shows a young man, naked in the way that statues of ancient gods were made, just pausing for a moment and looking with fierce eyes at the huge soldier Goliath that he is about to kill. The statue is 5.17 meter (17 ft) tall. It was placed in the piazza (public square) outside the Palazzo Vecchio where the town council met. After many years, the statue was put into an art gallery, the Accademia. A copy now stands in the piazza. People still go great distances to see the statue that he made.

Sistine Chapel ceiling

[change | change source]

In 1505 Michelangelo was invited to Rome by the newly elected Pope Julius II. Pope Julius was an old man. He wanted Michelangelo to design a grand tomb. It was to stand inside a church and have many carved figures which were to include several slaves to hold up part of the tomb and Old Testament prophets to sit in niches (openings in the walls). Michelangelo started work. He made a magnificent statue of Moses which is now in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli (St. Peter in Chains) in Rome. Many people go to look at this statue. The slaves were only partly carved. Four of them are now in the Accademia in Florence. The rest of the great plan was unfinished.

The main reason that Pope Julius' tomb was not finished was that the Pope had an idea for another artwork. The Sistine Chapel near St. Peter's Basilica had its walls painted by some famous artists from Florence. The Pope decided that Michelangelo should paint the ceiling. Michelangelo did not want to. He said that he was not a painter. But the Pope bullied Michelangelo until he agreed to do it. He told the Pope that he would do it "for God" and that he would only do it if the Pope let him paint it "in his own way".

The chapel was long and wide. Its curved ceiling was held up by twelve fan-shaped pieces of wall called "pendentives". Pope Julius told Michelangelo to paint one of the twelve apostles of Jesus on each pendentive. Michelangelo started to do this. Then he got a different idea and scraped off the work that he had done. Instead of apostles, he painted twelve prophets. Seven of them were men from the Old Testament but the other five were women and did not come from the Bible. They were five prophets from the Classical world. Like the prophets in the Bible, they had all told people about the birth of Jesus.

On the middle of the ceiling, instead of painting a starry sky, Michelangelo painted scenes from the Bible telling the story of Creation and the downfall of humanity. The most famous scene is the picture of God creating Adam. The ceiling was so famous that many artists tried to copy the way that Michelangelo had arranged and painted the figures.

Buildings and tombs in Florence

[change | change source]In 1513 Pope Julius II died. The next pope was Pope Leo X, a member of the Medici family. He gave Michelangelo several jobs in Florence, including designing the Medici Chapel to hold the tombs of his family members. Although not all the tombs were built, Michelangelo finished seven large statues including a "Madonna and Child". His pupils later completed the chapel.[19]

In 1527, the people of Florence became angry at the Medici for acting like princes. That was not the right way for a family to act, in a city that was a republic. The people threw the Medici out, but the Medici came back with an army and took over the city. Michelangelo was so upset at the behaviour of the Medici that he left his beloved city and never went back.

The Last Judgement

[change | change source]Pope Clement VII called Michelangelo back to the Sistine Chapel to paint the wall behind the altar with a huge scene of The Last Judgement. He worked on it from 1534 to 1541. At the centre it shows Jesus, surrounded by saints, sitting in judgement over the people of the Earth. To the left, people are rising from their graves and many are welcomed into Heaven. To the right, other people are being sent to Hell where they are dragged down by demons. It is a huge painting with many figures in it.

Like Adam and Eve on the ceiling, all the figures were shown naked. Some of the cardinals in the church said that it was wicked to paint saints, including the Virgin Mary, with no clothes on. They called Michelangelo "the painter of rude bits". There was a long argument about this because some people said that God had created everyone naked, so clothes would not be needed in Heaven. After Michelangelo's death another artist, Daniele da Volterra was called in to paint drapes on the figures. For the rest of his life, he was known as "the painter of pants".

St. Peter's Basilica

[change | change source]

In 1546, when Michelangelo was in his seventies, he was given one of his most important jobs. The old St. Peter's Basilica had been partly demolished and a new one designed by Bramante. But many architects had worked on it and it was still just at the beginning stages. Michelangelo was made the architect. He immediately improved the plan, had important parts made much stronger, and designed a huge dome, taller than any other domes in the world. He died before it was completed, but he left drawings and models so that the next architect, Giacomo della Porta, could finish what he had started. The dome of St. Peter's Basilica still stands as one of the greatest monuments of Christianity, and as a symbol of the city of Rome.

When Michelangelo died, his body was taken back to Florence and buried in the Basilica of Santa Croce (Church of the Holy Cross). On his tomb sit three mourning figures who symbolize Architecture, Painting and Sculpture.

-

Michelangelo's statue of Moses on the tomb of Pope Julius II

-

An Angel by Michelangelo

-

The Madonna of Bruges

-

The Burial of Jesus

-

The story of Adam and Eve from the Sistine Chapel Ceiling

-

The Story of the Great Flood from the Sistine Chapel Ceiling

Related pages

[change | change source]- Renaissance

- List of Renaissance artists

- Italian Renaissance art

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Raphael

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Sistine Chapel

- List of Italian painters

References

[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Web Gallery of Art, image collection, virtual museum, searchable database of European fine arts (1100–1850)". www.wga.hu. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ↑ "Michelangelo | biography". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Michelangelo. (2008). Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite.

- ↑ Emison, Patricia. A (2004). Creating the "Divine Artist": from Dante to Michelangelo. Brill. ISBN 9789004137097.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 11

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 C. Clément, Michelangelo, 5

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 9

- ↑ R. Liebert, Michelangelo: A Psychoanalytic Study of his Life and Images, 59

- ↑ C. Clément, Michelangelo, 7

- ↑ C. Clément, Michelangelo, 9

- ↑ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 18–19

- ↑ "Will the Real Michelangelo Please Stand Up?". Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 15

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 20–21

- ↑ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 17

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 24–25

- ↑ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, 19–20

- ↑ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, 26–28

- ↑ James Beck, Antonio Paolucci, Bruno Santi, Michelangelo. The Medici Chapel, London, New York, 2000.

Further reading

[change | change source]- Ackerman, James (1986). The Architecture of Michelangelo. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-2260-0240-8.

- Barenboim, Peter (with Heath, Arthur). 500 years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel, LOOM, Moscow, 2019. ISBN 978-5-906072-42-9

- Clément, Charles (1892). Michelangelo. Harvard University, Digitized 25 June 2007: S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, ltd.: London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Condivi, Ascanio; Alice Sedgewick (1553). The Life of Michelangelo. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01853-4.

- Baldini, Umberto; Liberto Perugi (1982). The Sculpture of Michelangelo. Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0447-X.

- Einem, Herbert von (1973). Michelangelo. Trans. Ronald Taylor. London: Methuen.

- Gilbert, Creighton (1994). Michelangelo On and Off the Sistine Ceiling. New York: George Braziller.

- Hibbard, Howard (1974). Michelangelo. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hirst, Michael and Jill Dunkerton. (1994) The Young Michelangelo: The Artist in Rome 1496–1501. London: National Gallery Publications.

- Liebert, Robert (1983). Michelangelo: A Psychoanalytic Study of his Life and Images. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02793-1.

- Pietrangeli, Carlo, et al. (1994). The Sistine Chapel: A Glorious Restoration. New York: Harry N. Abrams

- Sala, Charles (1996). Michelangelo: Sculptor, Painter, Architect. Editions Pierre Terrail. ISBN 978-2-87939-069-7.

- Saslow, James M. (1991). The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Rolland, Romain (2009). Michelangelo. BiblioLife. ISBN 978-1110003532.

- Seymour, Charles, Jr. (1972). Michelangelo: The Sistine Chapel Ceiling. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Stone, Irving (1987). The Agony and the Ecstasy. Signet. ISBN 0-451-17135-7.

- Summers, David (1981). Michelangelo and the Language of Art. Princeton University Press.

- Tolnay, Charles (1947). The Youth of Michelangelo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tolnay, Charles de. (1964). The Art and Thought of Michelangelo. 5 vols. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Néret, Gilles (2000). Michelangelo. Taschen. ISBN 9783822859766.

- Wilde, Johannes (1978). Michelangelo: Six Lectures. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Other websites

[change | change source]- "The Divine Michelangelo - Timeline of Michelangelo's Life and Major Works"

- Michelangelo in the "A World History of Art" Archived 2017-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Photographs of details at the Campidoglio

- Works by Michelangelo Buonarroti at Project Gutenberg

- The Digital Michelangelo Project

- The BP Special Exhibition Michelangelo Drawings — closer to the master Archived 2015-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Michelangelo's Drawings: Real or Fake? Archived 2006-04-11 at the Wayback Machine How to decide if a drawing is by Michelangelo.

- Models he used to make his sculptures and paintings

- "The Michelangelo Code" Archived 2009-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, suggesting Michelangelo's coded use of his knowledge of anatomy.

- "Michelangelo: The Man and the Myth" Archived 2012-03-24 at the Wayback Machine