Penobscot

Pαnawάhpskewi | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 2,278 enrolled members[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,278 (0.2%) | |

| Languages | |

| Abenaki, English | |

| Religion | |

| Wabanaki mythology, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Abenaki, Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy | |

The Penobscot (Abenaki: Pαnawάhpskewi) are Native Americans and First Nation from the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language is part of the Algonquian language family. They are part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The US government recognizes the Penobscot Nation as a tribe. They are in the regions of Maine, Atlantic provinces and Quebec. Their name means "the people of where the white rocks extend out."[2]

History

[change | change source]The Penobscot did hunting. They moved for different seasons.[3] They traveled in birch bark canoes. They hunted and fished at different times of the year. They joined the fur trade. They traded furs and got goods like alcohol. Many Natives died from European diseases. They were not immune to these diseases. Penobscot encountered French in Canada and English in New England. They supported the Americans in the American Revolution. However, Americans began to push Penobscot off their lands.[3] They were forced onto reservations. At the turn of the 19th century, the Penobscot gave up most of their land to Massachusetts. They could only stay on the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation. The tribe has sued the state of Maine several times. These have included issues like the right to hunt and land claims.[4]

Culture

[change | change source]Penobscot made baskets. They used sweet grass, brown ash, and birch bark. Baskets became more decorative with European trade.[5]

For the Penobscot, the lands have spiritual importance. Religion was closely connected to land. The landscape was part of a larger cosmology. Thus, land was very important for the Penobscot. A key figure in legends is Klose-kur-beh (Gluskbe). He gives the Natives practical and spiritual knowledge. He is as old as creation. According to Penobscot cosmology, Gluskbe warned about the greed and lust of white men. Animals and plants also had spiritual elements.[6][7] Natives converted to Christianity when Europeans arrived.[3]

Maps

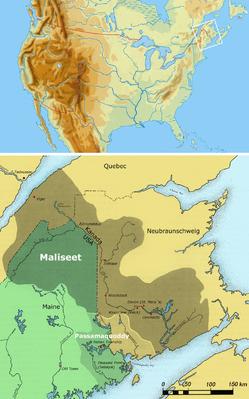

[change | change source]Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

- Maps of the Wabanaki Confederacy areas

-

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

-

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

References

[change | change source]- ↑ "Penobscot Indian Nation". US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ "Penobscot | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 The Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes. American Friends Service Committee, 1989.

- ↑ Diana Scully. "Maine Indian Claims Settlement: Concepts, Contexts, and Perspectives". 14 February 1995, Abbe Museum.

- ↑ "Penobscot - New World Encyclopedia". www.newworldencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ↑ Kolodny, Annette (2007). "Rethinking the "Ecological Indian": A Penobscot Precursor". Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment. 14 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1093/isle/14.1.1. ISSN 1076-0962. JSTOR 44086555.

- ↑ Kucich, John J. (2011). "Lost in the Maine Woods: Henry David Thoreau, Joseph Nicolar, and the Penobscot World". The Concord Saunterer. 19/20: 22–52. ISSN 1068-5359. JSTOR 23395210.