Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1981 | |

| 40th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989 | |

| Vice President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Jimmy Carter |

| Succeeded by | George H. W. Bush |

| 33rd Governor of California | |

| In office January 2, 1967 – January 6, 1975 | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Preceded by | Pat Brown |

| Succeeded by | Jerry Brown |

| President of the Screen Actors Guild | |

| In office November 16, 1959 – June 12, 1960 | |

| Preceded by | Howard Keel |

| Succeeded by | George Chandler |

| In office November 17, 1947 – November 9, 1952 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Montgomery |

| Succeeded by | Walter Pidgeon |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ronald Wilson Reagan February 6, 1911 Tampico, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 5, 2004 (aged 93) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Other political affiliations | Democratic (before 1962) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Relations | Neil Reagan (brother) |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Alma mater | Eureka College (BA) |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1937–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 18th AAF Base Unit |

Ronald Wilson Reagan (/ˈreɪɡən/ RAY-gən; February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor. He was the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. Before becoming president, he was the 33rd governor of California from 1967 to 1975. He was also the 9th and 13th president of the Screen Actors Guild from 1947 to 1952 and again from 1959 until 1960.

Reagan got a degree from Eureka College in 1932 and became a sports broadcaster in Iowa. In 1937, Reagan moved to California, where he became a movie actor. From 1947 to 1952, Reagan was the president of the Screen Actors Guild. In the 1950s, he worked in television and spoke for General Electric. From 1959 to 1960, he again was the Screen Actors Guild's president. In 1964, "A Time for Choosing" gave Reagan attention as a new conservative figure. He was elected governor of California in 1966. During his time as governor, he raised taxes, fixed the state's budget, and ended student protests in Berkeley. After running against and losing to president Gerald Ford in the 1976 Republican presidential primaries, Reagan won the Republican nomination and then a landslide victory over Democratic president Jimmy Carter in the 1980 United States presidential election.

In his first term, Reagan created "Reaganomics", which included economic deregulation and cuts in both taxes and government spending during a time of stagflation. He grew an arms race and had a more intense response with the Soviet Union. He also survived an assassination attempt, had a problems with public sector labor unions, made the war on drugs bigger, and ordered the invasion of Grenada in 1983. In the 1984 presidential election, Reagan was re-elected over former vice president Walter Mondale in another landslide victory. Foreign policy took over Reagan's second term, including the 1986 bombing of Libya, the Iran–Iraq War, the secret sale of arms to Iran to fund the Contras, and a more calm response in talks with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that led to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

Reagan left the presidency in 1989 with a lower unemployment rate than when he took office and lowered the country's inflation, however the national deficit grew.[1][2] He also had the government spend more money for the military and lowered taxes.[1] Being diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 1994, it made Reagan's post-presidency difficult and his physical and mental health quickly got worse. He died in June 2004 at the age of 93.

His presidency is a part of the Reagan era, and he is thought to be an important conservative figure in the United States.[3] Historians and scholars have ranked Reagan among the upper tier of American presidents, however he remains unpopular by some critics because of his domestic and tax policies.[4][5]

Early life

[change | change source]Reagan was born to Jack and Nelle Reagan on February 6, 1911, in a small apartment building in Tampico, Illinois.[6][7][8] He had an older brother named Neil.[9] His father was a Roman Catholic of Irish descent.[10] His mother was a Protestant of English and Scottish descent.[11]

The family moved to different places in Illinois when Reagan was a child. They moved to Monmouth and Galesburg.[12] His family finally moved to Dixon, Illinois.[7] They lived in a small house in Dixon.[13] His family was very poor and Reagan did not have much as a child.[11] In high school, Reagan enjoyed acting.[14] Reagan was athletic as well and played for the school's football team.[15] He became a lifeguard and saved 77 lives.[16]

Reagan studied at Eureka College in Illinois.[8] Between 1930 and 1931, during his college years, Reagan played football with the college team.[17] During this time, two Black teammates were not allowed to stay at a segregated hotel.[17] Reagan invited them to his parents' home nearby in Dixon.[17] He graduated in 1932.[8][18]

After college, Reagan became a sports announcer at news radio station WHO.[8][19] Reagan was also a broadcaster for the Chicago Cubs.[19][20] He was good at retelling baseball games.[20] In 1936, Reagan went with the Cubs to practice baseball at Santa Catalina Island in California.[21] While he was in California, Reagan got a seven-year contract with Warner Brothers.[22][23] He left his job as a radio announcer to start acting.[22][24]

Acting career

[change | change source]

Ronald Reagan was in fifty-three movies.[8] His first screen credit was the starring role in the 1937 movie Love Is on the Air. He then starred in many movies such as Dark Victory with Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart.[25] Before the movie Santa Fe Trail with Errol Flynn in 1940, he played the role of George "The Gipper" Gipp in the movie Knute Rockne, All American.[25] From his role in the movie, he got the lifelong nickname "the Gipper".[25] In 1941, experts voted him the fifth most popular star from the younger generation in Hollywood.[26]

Reagan's favorite acting role was as a double amputee in 1942's Kings Row.[27] In the movie, he says the line, "Where's the rest of me?" It was later used as the title of his 1965 autobiography. Many movie critics thought Kings Row to be his best movie.[28] Even though the movie was popular, it received bad reviews by New York Times critic Bosley Crowther.[29]

Although Reagan called Kings Row the movie that "made me a star",[30] he was unable to keep up with his success. This was because he was ordered to active duty with the U.S. Army in San Francisco two months after the movie's release.[31]

During World War II, Reagan was separated for four years from his movie career.[32] He served in the First Motion Picture Unit.[32] After the war, Reagan co-starred in movies such as The Voice of the Turtle, John Loves Mary, The Hasty Heart, Bedtime for Bonzo, Cattle Queen of Montana, Juke Girl, This Is the Army, The Winning Team, Tennessee's Partner, and Hellcats of the Navy, in which he worked with his wife, Nancy. Reagan's last movie was a 1964 movie The Killers.[33][34] Throughout his movie career, his mother, Nelle, wrote most of the responses to Reagan's fan mail.[35]

Reagan was also a spokesperson. He hosted the General Electric Theater since it was first shown in 1953.[36] He was fired in 1962.[36]

In 1957, Reagan won a Hollywood Citizenship Award, which was a special Golden Globe Award.[37]

President of the Screen Actors Guild

[change | change source]Reagan was first elected to the board of directors of the Screen Actors Guild in 1941.[38] After World War II, he quickly returned to Screen Actors Guild.[38] Reagan became the 3rd vice-president of the Screen Actors Guild in 1946.[38]

Reagan was nominated in a special election to become president of the Screen Actors Guild.[38] Reagan was elected in 1947. Reagan was president of the Screens Actors Guild from 1947 to 1952.[38] Reagan was re-elected president in 1959. He served only a year before resigning in 1960.[38]

Reagan led the Screen Actors Guild during labor disputes, the Taft–Hartley Act, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings and the Hollywood blacklist era.[38]

During the late 1940s, Reagan and his then-wife Jane Wyman gave the FBI names of actors whom they believed were communists.[39] Reagan even spoke at a special meeting at Congress on communism in Hollywood as well.[40]

Although Reagan gave out names of actors who were suspected communists, he did not agree with the way people were using these names. Reagan said "Do they expect us to constitute ourselves as a little FBI of our own and determine just who is a Commie and who isn't?"[39]

Marriages and children

[change | change source]Reagan met Jane Wyman while making Brother Rat in 1938.[41] He asked Wyman to marry him at the Chicago Theatre.[42] They were married in January 1940.[41] They had two children: Michael (adopted) and Maureen Reagan.[43] They had a third child, Christine Reagan, but she was stillborn.[43] With Reagan's growing political career and the death of their child, Wyman filed for divorce in 1948. The divorce was final in 1949.[8][43] Reagan was the first United States President to be divorced.[44]

In 1949, months after divorcing Wyman, Reagan met Nancy Davis.[45] Davis was an actress who was accidentally listed as a communist and asked Reagan to help.[46] After Reagan helped Davis, the two began dating.[46] Three years later, Reagan asked Davis to marry him in Beverly Hills, California while Nancy was two months pregnant.[47] They were married on March 4, 1952, in Hollywood, California.[8][46] Together, they had two children: Ron and Patti Reagan.[45] Nancy and Reagan were married for 54 years until Reagan died in 2004.[8]

Wyman died of natural causes on September 10, 2010.[43] She was aged 90.[43] Nancy died on March 6, 2016 of heart failure.[48] She was aged 94.[48]

Entering politics

[change | change source]

Reagan was very active in politics near the end of his acting career. Reagan used to be a Democrat.[49] He strongly supported the New Deal. He admired Franklin D. Roosevelt.[50] Over time, Reagan became a conservative Republican. This was because he thought the federal government had too much power and authority. He made a famous speech against socialized medicine (government-run health care).[51]

Reagan supported Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard Nixon for the United States presidency.[52] The last time Reagan supported a Democrat was when Helen Gahagan Douglas ran for the United States Senate.[53]

Speech for Barry Goldwater

[change | change source]During the 1964 presidential election, Reagan supported Republican candidate Barry Goldwater.[54] He made a famous speech called "A Time for Choosing" to support Goldwater.[54] In the speech he spoke against government programs and high taxes. Even though Goldwater did not win the election, Reagan gained popularity from it.[6] In his speech, Reagan said "You and I have a rendezvous with destiny. We will preserve for our children this, the last best hope of man on earth, or we will sentence them to take the first step into a thousand years of darkness".[55]

After Reagan gave this speech, many business people thought that Reagan could run for Governor of California.[56]

Governor of California, 1967–75

[change | change source]After giving a speech for Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign in 1964, he was persuaded to run for governor. Reagan ran as a Republican against the then governor, Pat Brown during the 1966 gubernatorial election.[57] Reagan won the election with 3,742,913 (57.55%) of the vote while Brown won 2,749,174 (42.27%) of the vote.[58] Reagan was inaugurated on January 2, 1967.[56]

During his years as Governor, Reagan stopped hiring government workers. He did this to slow the growth of California's workforce. Reagan also approved tax increases to balance the state budget.[56] Reagan worked with the Democratic Party majority in the state legislature to help create a major reform of the welfare system in 1971.[59] The reform helped give money to the poor and increase the pay of the rich.[59] During his term as governor, Reagan served as the President of the Republican Governors Association from 1968 to 1969.[60] In 1967, Reagan signed an act that did not allow the public carrying loaded guns.[61] In 1968, a petition to force Reagan into a recall election failed.[62]

Reagan ran briefly for president in 1968.[63] He was not nominated by the Republican Party at the 1968 Republican National Convention as Richard Nixon was nominated.[64]

On May 15, 1969, during the People's Park protests at the University of California, Berkeley, Reagan sent the California Highway Patrol and other officers to fight off the protests, in an event that became known as "Bloody Thursday".[65] Reagan then called out 2,200 state National Guard troops to occupy the city of Berkeley for two weeks to crack down on the protesters.[66]

Reagan ran for re-election in the 1970 gubernatorial election against assemblyman Jesse M. Unruh.[67] Reagan won 3,439,174 (52.83%) of the vote while Unruh won 2,938,607 (45.14%) of the vote.[68]

During his final term as governor, he played a major role in California's educational system.[56] He raised student loans. This caused a massive protest between Reagan and the college students.[56] Reagan would soon be criticized of his views of the educational system.[56]

Reagan left office on January 6, 1975, when Jerry Brown, Pat Brown's son, succeeded Reagan as governor.[56]

1976 presidential campaign

[change | change source]

In 1976, Reagan said he would run against President Gerald Ford to become the Republican Party's candidate for president.[69] Reagan soon became the conservative candidate with the support of groups such as the American Conservative Union, which became important supporters of his political run, while Ford was seen as a more moderate Republican.[70]

During his 1976 campaign, Reagan controversially used the pejorative phrase "welfare queen" to talk about Linda Taylor who illegally misused her welfare benefits in 1974.[71] He used Taylor and her criminal activities to defend why he was against social programs in the United States.[72]

Reagan picked United States Senator Richard Schweiker of Pennsylvania as his running mate.[73]

Reagan won a few primaries early such as North Carolina, Texas and California, but soon failed to win key primaries such as New Hampshire, Florida, and his native Illinois.[74][75]

During the 1976 GOP convention, Ford won the nomination with 1,187 delegates to Reagan's 1,070.[74] Ford would go on to lose the 1976 presidential election to the Democratic nominee, Jimmy Carter.[70]

Though he lost the nomination, Reagan got 307 write-in votes in New Hampshire, 388 votes as an Independent on Wyoming's ballot, and a single electoral vote from general election from the state of Washington.[76]

1980 presidential campaign

[change | change source]In November 1979, Reagan announced his plans to run for president again in the 1980 presidential election against President Jimmy Carter.[77] His campaign slogan, "Make America Great Again", was heavily used in the 1980 election and in Reagan's 1984 re-election campaign.[78] The slogan would be used by Presidents Bill Clinton and Donald Trump in their presidential campaigns.[79][80] Reagan also used the slogan "Morning in America" in this campaign.[81] Reagan had many people running for the nomination such as former Director George H. W. Bush, United States representatives John B. Anderson and Phil Crane, United States senators Bob Dole, Howard Baker, Larry Pressler and Lowell P. Weicker, Jr., Governor Harold Stassen, former Treasury Secretary John Connally and Republican businessman Ben Fernandez.[82] In May 1980, Reagan won enough delegates to win the Republican Party nomination.[83] At the 1980 Republican National Convention, Reagan named Bush as his running mate.[84]

Reagan's presidential campaign focused on lowering taxes to grow the economy,[85] less government in people's lives,[86] states' rights,[87] and a strong national defense.[88]

His relaxed and confident appearance during the Reagan-Carter debate on TV on October 28, made him more popular. He increased his lead over Carter in opinion polls.[89]

On November 4, Reagan won the election. He won 44 states with 489 electoral votes. Carter won 6 states and the District of Columbia with 49 electoral votes.[90] He also won the popular vote with 50.7% to Carter's 41.0%. Independent John B. Anderson won 6.6%.[89][90]

Presidency, 1981–89

[change | change source]

First term, 1981–85

[change | change source]Reagan was first sworn in as president on January 20, 1981.[91] In his inaugural address, he talked about the country's economic problems, saying "In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problems; government is the problem."[92] On the same day, hostages from the Iran hostage crisis were released.[91]

During the first two years of his presidency Reagan worked with a conservative majority in Congress. It was estimated that there were 230 votes in the 97th Congress. However, this changed following the midterm elections in 1982, with liberals regaining control of the House of Representatives. In the 98th Congress, there were now only 190 conservatives in the House. [93]

Assassination attempt

[change | change source]

Reagan was nearly killed in an assassination attempt that happened on Monday, March 30, 1981.[94][95] 69 days after becoming president, he was leaving after a speaking engagement at the Washington Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C.[95] He was shot by John Hinckley Jr.[95] Hinckley shot six bullets.[95]

White House Press Secretary James Brady was shot in the head.[95] Brady later recovered, but was paralyzed.[96] Another bullet hit officer Thomas Delahanty in the back of the neck, but he survived.[97][98] The third bullet hit Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy in the chest. McCarthy got shot so another bullet did not hit Reagan.[99] Reagan, Brady, Delahanty and McCarthy were the only ones injured during the event and they all survived.[95][94]

Reagan was taken to the George Washington University Hospital, which was the nearest hospital to the hotel and White House.[95] He suffered a punctured lung and a broken rib bone.[95] He lost about 3/4 of his blood.[95] Reagan soon made a fast recovery after doctors performed surgery.[95] It was later said that the bullet was one inch away from his heart.[95]

Domestic policies

[change | change source]In 1981, Reagan became the first president to propose a constitutional amendment on school prayer.[100] In 1985, Reagan expressed his disappointment that the Supreme Court ruling still bans a moment of silence for public schools, and said he had "an uphill battle."[101] In 1987, Reagan once again wanted Congress to support prayer in schools and end "the expulsion of God from America's classrooms."[102] People who did not support this, with some thinking it was going against the first amendment.[103] Reagan's Attorney General, William French Smith, thought it was unconstitutional.[103]

In the summer of 1981, the union of federal air traffic controllers went on strike. They broke a federal law that does not allow government unions to strike.[104] Reagan said that if the air traffic controllers "do not report for work within 48 hours, they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated".[105] They did not return and on August 5, Reagan fired 11,359 striking air traffic controllers who had ignored his order, and used supervisors and military controllers to handle the nation's commercial air traffic until new controllers could be hired and trained.[106]

The Reagan administration did not pay attention to the AIDS crisis in the United States in 1981.[107] AIDS research did not have the proper money needed during Reagan's administration. There were requests for more funding by doctors at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), but they were ignored. By the end of the first 12 months of the epidemic, more than 1,000 people had died of AIDS in the United States.[107][108] By the time President Reagan gave his first speech on the epidemic in 1987, 36,058 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS and 20,849 had died of it.[109] By the end of 1989, the year Reagan left office, 115,786 people had been diagnosed with AIDS in the United States, and more than 70,000 of them had died of it.[107] During his presidency, he also stopped giving out money that was given by the World Health Organization.[110] In 1988, before speaking to the United Nations, Reagan decided to give out the WHO funds.[110]

Reagan originally did not support making Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday a national holiday, because of cost concerns.[111][112] But on November 2, 1983, Reagan signed a bill to create a federal holiday honoring King.[113] The bill had passed the Senate by a count of 78 to 22[114] and the House of Representatives by 338 to 90.[115] The holiday was observed for the first time on January 20, 1986.[116] It is observed on the third Monday of January.[116]

Economic policies

[change | change source]

Reagan believed that the government should be small, not big. This means that the government should not interfere in people's lives very much or interfere with what businesses do.[8] He believed in supply-side economics, which was also called Reaganomics and Voodoo economics by people who did not like it during his term.[117] He lowered everybody's income taxes by 25%[118] and cut government spending.[119]

While he was president, inflation went from 13.5% to 4.1%.[2] Reagan's economic plan caused a bad economy during 1982, but the economy recovered in 1983.[120][121] However, people who did not like his economic plan pointed out an increase in the national debt from 31% to 50.8% of the country's GDP.[122] During his time in office, unemployment fell from 7.6% to 5.5% and the economy grew by 40%.[2]

Foreign policy

[change | change source]Reagan gave his "Evil empire" speech to the National Association of Evangelicals in Orlando, Florida on March 8, 1983.[123] He spoke about the nuclear arms race and said how communism would eventually fail.[123][124]

Reagan said "In your discussions of the nuclear freeze proposals, I urge you to beware the temptation of pride, the temptation of blithely declaring yourselves above it all and label both sides equally at fault, to ignore the facts of history and the aggressive impulses of an evil empire, to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding and thereby remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong and good and evil."[125]

In the "Evil Empire" speech, Reagan also said how he wanted NATO to use nuclear-armed intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Western Europe as a response to the Soviets adding new nuclear-armed missiles in Eastern Europe.[124]

In 1983, Reagan sent forces to Lebanon to stop the threat of the Lebanese Civil War.[126] On October 23, 1983, American forces in Beirut were attacked.[127] The Beirut barracks bombing killed 241 Americans and hurt more than 60 others by a suicide truck bomber.[128][127] Reagan removed all the Marines from Lebanon.[129]

Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, who had told the administration against having U.S. Marines in Lebanon, said there would be no change in the U.S.'s Lebanon policy.[130] Reagan met with his national security team and planned to target the Sheik Abdullah barracks in Baalbek, Lebanon.[131] A joint American–French air assault on the camp where the bombing was planned was also approved by Reagan and French President François Mitterrand, however U.S. Defense Secretary Weinberger successfully told Reagan to go against the mission.[132]

In September 1983, Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was shot down by the Soviet Union.[133] It killed one politician and many more Americans. Reagan was angry at the Soviets.[133] Reagan addressed the nation.[133] As a result, Reagan proposed that the American military's GPS would be allowed for civilian use.[134] In his address, Reagan said "I'm coming before you tonight about the Korean airline massacre, the attack by the Soviet Union against 269 innocent men, women, and children aboard an unarmed Korean passenger plane. This crime against humanity must never be forgotten, here or throughout the world."[135]

On October 25, 1983, Reagan ordered U.S. forces to invade Grenada, code named Operation Urgent Fury. Reagan said that there was a "regional threat posed by a Soviet-Cuban military build-up in the Caribbean" in Grenada.[136]

Operation Urgent Fury was the first major military operation done by U.S. forces since the Vietnam War. Some days of fighting started, but it resulted in a U.S. victory.[136] In mid-December, U.S. forces withdrew from Grenada after a new form of government was created there.[136]

1984 re-election campaign

[change | change source]

Reagan was once again nominated for president at the 1984 Republican National Convention.[137] His Democratic opponent was former Vice President Walter Mondale of Minnesota.[138]

During the first presidential debate, many said Reagan lost the debate and there were rumors about Reagan's health citing his confusion on stage.[139] Many thought Reagan was showing the early stages of Alzheimer's disease.[140] In the second debate, Reagan improved his performance and when asked about questions of his age, he said "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience."[141] Reagan's statement made the entire audience laugh including the moderators and Mondale himself.[141] Reagan also repeated his 1980 debate phrase: "There you go again".[141]

Reagan was re-elected in 1984 in a landslide victory. Reagan won 49 out of the 50 states.[138] He carried more electoral votes than any other president in American history.[138]

Second term, 1985-89

[change | change source]

Reagan was sworn in as president once again on January 20, 1985. He was sworn in at the White House due to cold weather.[138] In the weeks after, he changed his staff by moving White House Chief of Staff James Baker to Secretary of the Treasury and naming Treasury Secretary Donald Regan to Chief of Staff.[142]

Foreign policy

[change | change source]Reagan became friends with the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher.[138] Both of them held meetings about the Soviet Union's threat and how to end the Cold War. Reagan became the first American president to ever address the British Parliament.[143]

In foreign policy, Reagan ended détente (the policy of being friendly to the Soviet Union) by ordering the largest peacetime military buildup in American history.[144][145] The U.S. government had to borrow a lot of money to pay for it. He had many new weapons built. Soon, the U.S. began to research a missile defense system that would destroy missiles. It was to prevent a nuclear war from happening.[146] The program was called Strategic Defense Initiative. It was nicknamed "Star Wars".[146]

He directed money to anti-communist movements all over the world that wanted to overthrow their communist government. He ordered multiple military operations including the invasion of Grenada and the Libya bombing.[8][147]

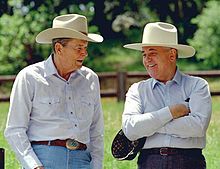

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became the new leader of the Soviet Union (which was in bad shape and soon to collapse). Reagan had many talks with him. Their first meeting together was at the Reykjavík Summit in Iceland.[148] They became good friends.[149][150]

In May 1985, Reagan and Chancellor Helmut Kohl were scheduled to visit a military cemetery in Bitburg, Germany to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II.[151] The visit caused controversy as the cemetery had members of the Waffen-SS buried there and Reagan did not schedule a visit to a concentration camp.[151] As a result, a trip to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was added to Reagan's schedule where he made a few remarks about the Holocaust and the end of the war.[151] Reagan responded by saying "This visit has stirred many emotions in the American and German people too. Some old wounds have been reopened, and this I regret very much, because this should be a time of healing."[152]

During the Reagan presidency, relations between Libya and the United States were not good. In early April 1986, relations became worse when a bomb exploded in a Berlin discothèque.[153] It resulted in the injury of 63 American military personnel and the death of one serviceman.[153] On April 15, 1986, the United States launched many attacks in Libya.[154][155] British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher allowed the U.S. Air Force to use Britain's air bases to launch the attack.[155] The attack was done to stop Gaddafi's "ability to export terrorism", offering him "incentives and reasons to alter his criminal behavior".[154] The president addressed the nation from the Oval Office after the attacks started. He said "When our citizens are attacked or abused anywhere in the world on the direct orders of hostile regimes, we will respond so long as I'm in this office".[155] Many countries and the United Nations did not like Reagan's decision to bomb Libya.[156] The United Nations said that Reagan broke "the Charter of the United Nations and of international law".[156]

In the 1980s, apartheid in South Africa was becoming more violent and a global issue.[157] The Democrats in the Senate tried to pass the Anti-Apartheid Act in September 1985, but could not pass because of a Republican filibuster.[158] Reagan created his own sanctions for South Africa, but Democrats thought they were weak.[159]

The bill was re-introduced in 1986 and brought up for a vote even though Republican wanted to block it to give Reagan's sanctions time to work.[160] It passed the House with Reagan publicly against it.[161] Later the Senate approved the bill with a 84-14 vote.[162] On September 26, 1986, Reagan vetoed the bill saying that it would cause an "economic war".[163] Republican Senator Richard Lugar led the Senate to override Reagan's veto.[164] The veto was reversed by Congress (by the Senate 78 to 21, the House by 313 to 83) on October 2.[165] The veto override was the first one on a presidential foreign policy veto in the 20th century.[163] In response to the veto override, Reagan said "I believe, are not the best course of action; they hurt the very people they are intended to help. My hope is that these punitive sanctions do not lead to more violence and more repression. Our administration will, nevertheless, implement the law".[166] Reagan also criticized those who were against apartheid such as the African National Congress (ANC).[157] He thought the ANC was dangerous and supported communism.[157] On a trip to the United States after winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, Bishop Desmond Tutu said that Reagan's policy was "immoral, evil and totally un-Christian."[157]

Reagan's popularity was badly hurt by the political scandal Iran-Contra Affair.[8][167] The government illegally sold weapons to Iran.[167] It later used the profits to support a Nicaraguan terrorist group called the Contras.[167] Reagan told the American people he did not know anything about the scandal.[167] Reagan gave money to the Contras to fight off the Communist rule of Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, but when it became too expensive, Congress made it illegal to pay the Contras.[167] As a result, members of Reagan's administration began to send money illegally to the Contras.[167] The New York Times said that Reagan's 1980 campaign made a deal with Iran in which they would release American hostages after Jimmy Carter left office.[168]

His United States National Security Advisor John Poindexter was charged with multiple felonies and later resigned.[169] Reagan later nominated former Ambassador Frank Carlucci to replace Poindexter.[170] His Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger was thought to be guilty, but resigned before a trial could begin.[171] Reagan later nominated Carlucci to be his Defense Secretary.[170] Oliver North, a member of the United States National Security Council, resigned and was questioned for his role in the affair.[172] In February 1987, White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan also resigned because of personal problems he had with Reagan and First Lady Reagan about his handling of the affair.[173]

Soon, he told the American people that it was his fault. In his apology, Reagan said "Let's start with the part that is the most controversial. A few months ago I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages. My heart and my best intentions still tell me that's true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not."[174] In the end, fourteen administration officials were indicted and eleven convictions resulted.[174] The rest of those indicted or convicted were all pardoned by President George H. W. Bush, who had been Vice President at the time of the affair.[175]

In 1987, Reagan traveled to Berlin to give a speech at the Berlin Wall.[176] That is where he gave one of his well known speeches of his presidency.[176] Former West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl said he would never forget standing near Reagan when he told Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall. "He was a stroke of luck for the world, especially for Europe."[177] Talking about the Brandenburg Gate and the Berlin Wall he said that Gorbachev should support liberalization and that by tearing down the Berlin Wall it would bring freedom and peace to Germany.[178]

During his term as president, Reagan saw the change in the mood of the Soviet leadership with Mikhail Gorbachev.[179] Months after his Berlin Wall speech, Gorbachev said his plans to work with Reagan for a big arms agreement.[180] Reagan and Gorbachev signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty which banned nuclear weapons being launched between the United States and the Soviet Union.[181]

When Reagan visited Moscow for the fourth summit in 1988, he was seen as a celebrity by the Soviets.[182] A journalist asked the president if he still thought the Soviet Union the evil empire. "No", he replied, "I was talking about another time, another era".[182] In November 1989, ten months after Reagan left office, the Berlin Wall was torn down, the Cold War was officially declared over at the Malta Summit on December 3, 1989, and two years later, the Soviet Union collapsed.[183]

Domestic policies

[change | change source]Reagan announced a War on Drugs in 1982, because he was worried about the growing number of people using crack.[184] Even though Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs during the 1970s, Reagan used more militant policies.[185] First Lady Nancy Reagan created her "Just Say No" campaign against drug use to children.[186]

In late 1984, Reagan visited Temple Hillel and became the first sitting president since George Washington to visit a synagogue.[187][188]

In 1986, Reagan signed a drug enforcement bill that made sure there would be $1.7 billion to fund the War on Drugs. It created a mandatory minimum penalty for drug offenses.[189] The bill was criticized for creating racial inequalities and mass imprisonment of African-Americans.[189] As a result of Reagan's war on drugs, drug abuse became a growing problem among Americans at the time.[190]

In 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded, killing everyone on board. The entire country was shocked. Reagan moved that date to his 1986 State of the Union Address because the tragedy.[191] It was the first time that a President of the United States postponed a State of the Union Address.[191] Afterwards, Reagan addressed the nation,[192] where he said "We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and 'slipped the surly bonds of Earth' to 'touch the face of God'."[193]

Reagan ordered for a commission to be created to investigate the explosion.[194] When the commission created a list of recommendations to avoid another explosion, Reagan ordered NASA to start using the new safety measures within thirty days.[195][196]

In November 1986, Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act.[197] It helped some immigrants to get jobs and become legal citizens.[197] In that same year, the Statue of Liberty was just re-opened after being renovated. Reagan was at the opening ceremony when he said "The legalization provisions in this act will go far to improve the lives of a class of individuals who now must hide in the shadows, without access to many of the benefits of a free and open society. Very soon many of these men and women will be able to step into the sunlight and, ultimately, if they choose, they may become Americans."[198]

In January 1987, U.S. Representative Tom Foley introduced the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 to Congress as a way to give reparation to Japanese-Americans who were interned by the United States during World War II.[199] It passed the House in September 1987 and was sent to the Senate where it was passed in April 1988.[200] Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act into law on August 10, 1988, granting USD $20,000 in payments beginning in 1990.[199][200] A total of 82,219 Japanese-Americans received checks.[201]

Supreme Court nominations

[change | change source]During his 1980 campaign, Reagan promised that, if elected, he would nominate the first female Supreme Court Associate Justice.[202] On July 7, 1981, he nominated Sandra Day O'Connor to replace the retiring Justice Potter Stewart.[203] Reagan said that O'Connor "[was] truly a person for all qualities".[204] O'Connor was confirmed by the United States Senate with a vote of 99–0.[203]

In his second term in 1986, Reagan nominated William Rehnquist to replace Warren E. Burger as Chief Justice.[205] He named Antonin Scalia to fill the empty seat left by Rehnquist.[205]

After Associate Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. announced his retirement in June 1987, Reagan picked conservative jurist Robert Bork to replace him in 1987.[206] Senator Ted Kennedy was strongly against Bork.[206] Kennedy said Bork was not strong on states', civil or women's rights.[206] Kennedy said that "Robert Bork's America is a land where women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, police could break down citizens' doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the Government, and the doors of the Federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is—and is often the only—protector of the individual rights that are the heart of our democracy".[207]

Bork's nomination was not approved by the United States Senate with a vote of 58–42.[208] Reagan then nominated Douglas H. Ginsburg, but Ginsburg ended up not wanting the role as it was revealed he used cannabis.[209] Reagan later nominated Anthony Kennedy to replace Powell, Jr. and he was approved with a vote of 97–0.[210]

End of the Reagan presidency

[change | change source]Reagan left office with high rankings on January 20, 1989, when his Vice President George H. W. Bush became president.[8] Reagan was the oldest president at that time until former President Donald Trump was elected in 2024 at the age of 78.[211]

Reagan and his wife, Nancy, soon returned home in Bel Air, Los Angeles, California.[212][6] They also visited their ranch, Rancho del Cielo. Reagan gave a speech at the 1992 Republican National Convention giving his support for Bush's re-election campaign in the 1992 presidential election.[213] Even after when he left office, Reagan had a close friendship with both Thatcher and Gorbachev.[138]

After the presidency

[change | change source]

In November 1991, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library was dedicated and opened to the public in Simi Valley, California.[214]

In June 1989, Reagan was honored with Honorary Knighthood and received the Order of the Bath presented by Queen Elizabeth II.[215] He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1993 by President George H. W. Bush.[216] He was the first former living president to receive the honor.[217] Soon afterwards the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation created the Ronald Reagan Freedom Award for people who made a big change for freedom.[218]

In 1990, Reagan wrote an autobiography titled, An American Life.[138]

In May 1994, Reagan, along with former presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, wrote to the U.S. House of Representatives in support of banning "semi-automatic assault guns."[219]

Assault

[change | change source]On April 13, 1992, Reagan was assaulted by an anti-nuclear protester during a speech while accepting an award from the National Association of Broadcasters in Las Vegas.[220] The protester was Richard Paul Springer. He smashed a 2-foot-high (60 cm) 30-pound (13.5 kg) crystal statue of an eagle that the broadcasters had given to Reagan. Pieces of glass hit Reagan, but he was not injured.[221]

Springer was the founder of an anti-nuclear group called the 100th Monkey. Following his arrest on assault charges, a Secret Service spokesman did not say how Springer got past the agents.[222] Later, Springer pled guilty to the federal charge of interfering with the Secret Service, but other felony charges of assault and fighting against officers were dropped.[223]

Health issues

[change | change source]Early in his presidency, Reagan started wearing a hearing aid, first in his right ear[224] and later in his left as well.[225][226] In 1985, he had colon cancer and skin cancer removed at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.[227] In 1987, Reagan had surgery to remove a polyp of the nose.[227] Also in that year, Reagan went into surgery for an enlarged prostate.[228]

In her memoirs, former CBS White House correspondent Lesley Stahl remembers her final meeting with the president in 1986.[229] She said that "Reagan didn't seem to know who I was. I have to go out on the lawn tonight and tell my countrymen that the president of the United States is a doddering space cadet."[229] At the end of the meeting, Stahl saw that Reagan became focused again. She later said that "I had come that close to reporting that Reagan was senile."[229]

On January 7, 1989, Reagan had surgery at the Reed Army Medical Center to fix a Dupuytren's contracture of the ring finger of his left hand.[230] The surgery lasted for more than three hours.[230] Eight months later in September, Reagan had surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota to remove fluid from his brain because of an injury from falling off a horse.[231] The surgery lasted just over an hour.[231]

In 1994, Reagan was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.[232][233]

On November 5, 1994, Reagan wrote a public letter about having Alzheimer's disease.[232] In the letter, Reagan said that he was "one of the millions of Americans who will be [affected] with Alzheimer's disease" and that he will begin "the journey that will lead me into the sunset of my life".[234]

After announcing his disease, many people sent supporting letters to his California home.[235] There was also an opinion based on unfinished evidence that Reagan had shown symptoms of mental decline while still in office.[236]

In 1995, the Ronald and Nancy Reagan Research Institute was dedicated in Chicago, Illinois.[237] It is an institution that can help people with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.[237]

Reagan fell at his Bel Air home on January 13, 2001. He broke his hip.[238] The fracture was repaired the next day. Reagan, 89 years old, returned home later that week, but he then had to do difficult physical therapy at home.[238]

Final years

[change | change source]As the years went on, Alzheimer's disease slowly destroyed Reagan's mental capacity.[239] He was only able to recognize a few people, including his wife, Nancy.[239] He remained active during his last years. He took walks through parks near his home and on beaches, played golf regularly, and until 1999 he often went to his office in nearby Century City.[239]

On February 6, 2001, Reagan reached the age of 90, becoming the third former president to do so (the other two being John Adams and Herbert Hoover, with Gerald Ford, George H. W. Bush, and Jimmy Carter later reaching 90).[240]

Reagan appeared in public not as much as the disease got worse. His family said that he would live alone with his wife Nancy. Nancy Reagan told CNN's Larry King in 2001 that very few visitors were allowed to see her husband because she felt that "Ronnie would want people to remember him as he was."[241] In that same year, Reagan's daughter, Maureen Reagan, died from melanoma at the age of 60.[242]

The USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) was finished in 2001.[243] A ceremony was held in March 2001.[243] Reagan's wife, Nancy lead the ceremony.[243] She christened the ship.[243] Reagan could not go because he was very sick.[243]

Following her husband's diagnosis and death, Nancy became a stem-cell research advocate. She urged Congress and President George W. Bush to support federal funding for embryonic stem cell research. President Bush opposed the idea. In 2009, she praised President Barack Obama for lifting restrictions on such research.[244] Mrs. Reagan believed that it could lead to a cure for Alzheimer's.[245] Nancy died on March 6, 2016, at the age of 94.[48]

Death and funeral

[change | change source]On June 5, 2004, Reagan died at the age of 93 of pneumonia, caused by Alzheimer's disease, in his home in Bel Air, Los Angeles, California.[7] A short time after his death, Nancy Reagan released a statement saying, "My family and I would like the world to know that President Ronald Reagan has died after 10 years of Alzheimer's disease at 93 years of age. We appreciate everyone's prayers."[246]

Reagan was granted a state funeral. Reagan's state funeral was the first in the United States since Lyndon B. Johnson in 1973.[247] It was held at the Washington National Cathedral on June 11 and presided by former Missouri United States senator John Danforth.[248] President George W. Bush and former presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton went to the funeral.[247] First Lady Laura Bush and former first ladies Betty Ford, Rosalynn Carter, and Barbara Bush also went.[247]

Former First Lady Lady Bird Johnson did not go to the funeral because of poor health. Reverend Billy Graham, who was Reagan's first choice to lead the funeral, could not go because he was recovering from surgery.[249] Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor also went to the funeral and delivered a passage from the Bible.[249] The funeral was led by Reagan's close friend and pastor Michael Wenning.[250]

Foreign leaders also went to Reagan's funeral, Mikhail Gorbachev, Prime Minister of United Kingdom Tony Blair, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and interim presidents Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan and Ghazi al-Yawer of Iraq.[247] Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Margaret Thatcher, former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and both former President George H. W. Bush and President George W. Bush gave eulogies.[247]

Reagan was buried later that day in an underground vault at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.[247][251] His tomb reads, "I know in my heart that man is good. That what is right will always eventually triumph. And that there is purpose and worth to each and every life".[252]

Legacy

[change | change source]Reagan, by public opinion, is one of the most popular American presidents.[253] His legacy is strongly admired among many conservatives and Republicans.

According to USA Today, "Reagan transformed the American presidency in ways that only a few have been able to."[254] His role in the Cold War made his image more popular as a different kind of leader as both Reagan and Gorbachev wanted to end nuclear tensions and the war.[255][256]

Reagan ranked third of post–World War II presidents in a 2007 Rasmussen Reports poll, fifth in an ABC 2000 poll, ninth in another 2007 Rasmussen poll, and eighth in a late 2008 poll by British newspaper The Times.[257][258][259] In 2011, British historians released a survey to rate American presidents. This poll of British experts in American history and politics said that Reagan is the eighth greatest American president.[260]

Some people of the opposite party, the Democratic Party, had some good thoughts about Reagan as well.[261] Democrats who support Reagan are called Reagan Democrats.[261] His presidency is sometimes called the Reagan Era because of the changes it brought during Reagan's time as president.[262] During his presidency, Reagan was known for his witty charm and his warm optimism.[263] Reagan was also supported by young voters, who began to support the Republican party as a result.[7][264]

The legacy of his economic policies is still divided between people who believe that the government should be smaller and those who believe the government should take a more active role in regulating the economy.[5] Some saw that his tax cuts only helped the rich and ignored the poor.[5] While some of his foreign policies were not popular, many thank Reagan for peacefully ending the Cold War.[265]

In 2019, an audio recording from 1971 of a conversation between Reagan and President Richard Nixon was released in which Reagan called African diplomats at the United Nations "monkeys". His quote has been called racist.[266][267][268]

Reagan was known as the "Teflon president" because any criticism or scandals against him never stuck or affected his popularity.[269]

Honors

[change | change source]

In 2000, Ronald and Nancy Reagan received the Congressional Gold Medal in "recognition for their service to their nation".[270]

In August 2004, a tribute to Reagan was shown at the 2004 Republican National Convention presented by his son, Michael Reagan.[271]

In June 2007, Reagan received the Order of the White Eagle from Poland's president, Lech Kaczyński, for Reagan's work to end communism in Poland.[272] Nancy Reagan traveled to Warsaw to accept the award for her husband.[272]

On June 3, 2009, a statue of Reagan was added in the United States Capitol rotunda. The statue represents the state of California in the National Statuary Hall Collection.[273] Following Reagan's death, both major American political parties agreed to place a statue of Reagan instead of that of Thomas Starr King.[274]

Also in June 2009, President Obama signed the Ronald Reagan Centennial Commission Act into law.[275] It created a commission to plan activities to mark the upcoming centenary of Reagan's 100 birthday.[275]

On July 4, 2011, a statue of Reagan was presented in London. It is outside of the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square.[276] The ceremony was supposed to be attended by Reagan's wife Nancy, but she did not attend. Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice took her place and read a statement from her. British Prime Minister during Reagan's presidency, Baroness Thatcher, was also unable to attend due to poor health.[276]

A statue of Reagan was presented in November 2011 in Warsaw, Poland. President of Poland Lech Wałęsa was there.[277] February 6 has been known as Ronald Reagan Day in 21 states across the United States in honor of his birthday.[278]

In 2011, Reagan was added to the National Radio Hall of Fame.[279]

In 2016, Ronald and Nancy Reagan were honored in the Presidential $1 Coin Program in August 2016.[280] He was the last president honored in the program.[280]

Related pages

[change | change source]- Make America Great Again

- Reagan Era

- Reaganomics

- What would Reagan do?

- Killing Reagan

- Ronald Reagan Speaks Out Against Socialized Medicine

References

[change | change source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Reagan left stamp on economy". The Gadsden Times. June 5, 2004. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Ronald Reagan's Enduring Economic Legacy". Forbes. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ "How Reagan Helped Usher In A New Conservatism To American Politics". WPR. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Americans Judge Reagan, Clinton Best of Recent Presidents". Gallup. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Ronald Reagan Wasn't the Good Guy President Anti-Trump Republicans Want You to Believe In". Teen Vogue. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Ph.D, J. David Woodard (2012-01-06). Ronald Reagan: A Biography. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39639-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Ronald Reagan dies at 93, CNN, 2004, retrieved January 25, 2010

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 The White House, retrieved January 25, 2010

- ↑ Holloway, Lynette (December 13, 1996). "Neil Reagan, 88, Ad Executive And Jovial Brother of President". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ↑ "A Complicated Man: Ronald Reagan's Father". Catholic Exchange. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Jack and Nelle". Catholic Education. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Tom Wilson: Reagan revisits his boyhood home". Galesburg.com. February 14, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan's Roots Run Deep in Dixon Illinois". Dixongov. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ Brands 2015, p. 14.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan and Sports". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan Timeline". NPR.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "'Closest Friend' Was Reagan Teammate". The Washington Post. January 15, 1986. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Ronald W. Reagan Society". Eureka College. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Former president was sports announcer". ESPN. June 5, 2004. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "THE REAGAN PLAY-BY-PLAY STILL PLAYS". The New York Times. March 31, 1985.

- ↑ "How Spring Training put Ronald Reagan on the path to stardom -- and the presidency". MLB. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Reagan and Baseball". Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum. Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan: His Life : The Early Years". The Los Angeles Times. November 4, 1991. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Reagan's Life & Times". www.reaganfoundation.org. Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "How Reagan got his Gipper nickname". Sidney Morning Herald. June 8, 2004. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ "Cupid's Influence on the Film Box-Office". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1956). Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia. October 4, 1941. p. 7 Supplement: The Argus Week-end Magazine. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ↑ Reagan, Ronald (1965). Where's the Rest of Me?. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce. ISBN 0-283-98771-5.

- ↑ Wood, Brett. "Kings Row". TCM website. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 24, 2009.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (February 3, 1942). "The Screen; 'Kings Row,' With Ann Sheridan and Claude Rains, a Heavy, Rambling Film, Has Its First Showing Here at the Astor". The New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan Appears as Drake McHugh in Kings Row". World History Project.org. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan applies for transfer to Army Air Force". History.com. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 George J. Siegel. "1st Motion Picture Unit". Military Museum. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan". IMDb. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan's Last Movie". TV Guide. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ "Truth exposed on writer of Reagan letters". Journal Standard. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Michael Reagan (February 4, 2011). "Ronald Reagan's Son Remembers The Day When GE Fired His Dad". investors.com. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan". Golden Globes. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 "Screen Actors Guild Presidents: Ronald Reagan". Screen Actors Guild. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Hollywood: Unmasking Informant T-10". Time. September 9, 1985. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Reagan, Hollywood and the Red Scare" (PDF). Reagan Foundation. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Ronald Reagan and Jane Wyman's love story had an unhappy ending". BND. Archived from the original on November 19, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ "DISPUTE OVER THEATER SPLITS CHICAGO CITY COUNCIL". The New York Times.com. May 8, 1984. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 Elizabeth Blair (September 10, 2007). "Oscar Winner Jane Wyman, Reagan's First Wife, Dies". NPR. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Stuart Fox (June 18, 2010). "How Many Presidents Have Been Divorced?". Live Science.com. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "First Ladies: Nancy Reagan". The White House. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 "Ronald Reagan and Nancy Davis marry". History.com. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan married Nancy because she was pregnant, daughter writes in new book". Yahoo. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Lou Cannon (March 6, 2016). "Nancy Reagan, an Influential and Stylish First Lady, Dies at 94". The New York Times.com. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Hornick, Ed (February 6, 2011). "Reagan's myth has grown over time". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ John Zogby (February 23, 2011). "Reagan and FDR Share One Thing: Title of Greatest". Forbes. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Eric Black (March 7, 2019). "Reagan warning about Medicare: S-word scare tactic goes way back". Minnpost. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Regan, Ronald (1990). An American Life: The Autobiography. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671691988. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ↑ "The Crist Switch: Top 10 Political Defections". Time. May 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Reagan, Ronald (1964). "Address on Behalf of Senator Barry Goldwater: "A Time for Choosing"". Presidency.UCSB.edu. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan -- A Time for Choosing". Americanhetoric.com. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 "Ronald Reagan". Governors.library.ca.gov. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Reagan's 1966 Gubernatorial Campaign Turns 50: California, Conservatism, and Donald Trump". KCET. August 19, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Anderson, Totton J.; Lee, Eugene C. (June 1967). "The 1966 Election in California". The Western Political Quarterly. 20 (2): 535–554. doi:10.2307/446081. ISSN 0043-4078. JSTOR 446081. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "California Legislature Approves Welfare Reform Bill After Compromise With Reagan". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ↑ "Chris Christie kicks off term as Republican Governors Association chairman". Daily News. New York. 21 November 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ "From "A Huey P. Newton Story"". PBS. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Recall Idea Got Its Start in L.A. in 1898". Los Angeles Times. July 13, 2003.

- ↑ Pemberton 1997, p. 76.

- ↑ Gould 2010, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ "The Battle for People's Park, Berkeley 1969: when Vietnam came home". The Guardian. July 6, 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Jeffery Kahn (8 June 2004). "Ronald Reagan launched political career using the Berkeley campus as a target". Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ Anderson, Totton J.; Bell, Charles G. (June 1971). "The 1970 Election in California". The Western Political Quarterly. 24 (2): 252–273. doi:10.2307/446870. JSTOR 446870. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ↑ "1970 Gubernatorial General Election Results – California". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ↑ "How Ronald Reagan's 1976 Convention Battle Fueled His 1980 Landslide". History. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "Biography of Gerald R. Ford". The White House. Archived from the original on April 11, 2007. Retrieved March 29, 2007. Ford called himself "a moderate in domestic affairs, a conservative in fiscal affairs, and a dyed-in-the-wool internationalist in foreign affairs."

- ↑ Demby, Gene (December 20, 2013). "The Truth Behind The Lies Of The Original 'Welfare Queen'". NPR. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ↑ "'Welfare Queen' Becomes Issue in Reagan Campaign". The New York Times. February 15, 1976. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ↑ John Gizzi (5 August 2015). "Richard Schweiker is Ronald Reagan's Running Mate". Newsmax. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "1976 New Hampshire presidential Primary, February 24, 1976 Republican Results". New Hampshire Political Library. Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan vs. Gerald Ford: The 1976 GOP Convention Battle Royal". National Interest. April 16, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". U.S. National Archives and Records Admin. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan Presidential Campaign Announcement". C-Span. November 13, 1979. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Matt Taibbi (March 25, 2015). "Donald Trump Claims Authorship of Legendary Reagan Slogan; Has Never Heard of Google". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ Margolin, Emma (September 9, 2016). "Who really first came up with the phrase 'Make America Great Again'?". NBC. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Bill Clinton suggests Trump slogan racist – but he used the same one". Fox News. September 9, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Morning in America". US History.org. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ "1980: Presidential Campaigns and References". Presidential Campaigns and Elections. 5 July 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Bush Ends 2-Year Quest, Concedes '80 Republican Nomination to Reagan". The Washington Post. May 27, 1980. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Josh Zeitz (July 13, 2016). "5 Times the Vice Presidential Pick Surprised Everyone". Politico. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ↑ Uchitelle, Louis (September 22, 1988). "Bush, Like Reagan in 1980, Seeks Tax Cuts to Stimulate the Economy". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ↑ Hakim, Danny (March 14, 2006). "Challengers to Clinton Discuss Plans and Answer Questions". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ↑ Douglas E. Kneeland (August 4, 1980). "Reagan Campaigns at Mississippi Fair; Nominee Tells Crowd of 10,000 He Is Backing States' Rights". The New York Times. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ↑ Lou Cannon (August 18, 1980). "Reagan: 'Peace Through Strength'". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Cannon, Lou (4 October 2016). "Ronald Reagan: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 "1980 Presidential Election Results". Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Weisman, Steven R. (January 21, 1981). "Reagan Takes Oath as 40th President; Promises an 'Era of National Renewal'—Minutes Later, 52 U.S. Hostages in Iran Fly to Freedom After 444-Day Ordeal". New York Times. p. A1.

- ↑ Murray, Robert K.; Tim H. Blessing (1993). Greatness in the White House. Penn State Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-271-02486-0.

- ↑ Movers & Shakers: Congressional Leaders in the 1980s, John B. Shlaes, Eric M. Licht, 1985 P.17

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "Assassination Attempt". Reagan Library. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ 95.00 95.01 95.02 95.03 95.04 95.05 95.06 95.07 95.08 95.09 95.10 "Remembering the Assassination Attempt on Ronald Reagan". CNN. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ↑ "James Brady, Reagan spokesman and anti-gun activist, dies at 73". CBS News. August 4, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Wounded officers struggle with news of John Hinckley Jr.'s release". Chicago Tribune. 28 July 2016. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ "Personality Spotlight: Thomas K. Delahanty: Police officer wounded by Reagan's side..." UPI. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ↑ Crean, Ellen (June 11, 2004). "He Took a Bullet for Reagan". CBS.

'In the Secret Service,' [McCarthy] continued, 'we're trained to cover and evacuate the president. And to cover the president, you have to get as large as you can, rather than hitting the deck.'

- ↑ David M. Ackerman, The Law of Church and State: Developments in the Supreme Court Since 1980. Novinka Books, 2001. p. 2.

- ↑ George de Lama, Reagan Sees An "Uphill Battle" For Prayer In Public Schools Archived 2014-11-10 at the Wayback Machine. June 7, 1985, Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Stuart Taylor Jr., High Court Accepts Appeal Of Moment Of Silence Law. January 28, 1987, The New York Times.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "Why Reagan grabbed the initiative on school prayer". The Christian Science Monitor. May 10, 1982. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ Herbert R. Northrup, "[www.jstor.org/stable/2522839 The Rise And Demise Of PATCO]", Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Jan 1984, Vol. 37 Issue 2, pp 167–184

- ↑ "Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session With Reporters on the Air Traffic Controllers Strike". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. 1981. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan fires 11,359 air-traffic controllers". History. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 Bronski, Michael (14 November 2003). "Rewriting the Script on Reagan: Why the President Ignored AIDS". Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ↑ Shilts, Randy (27 November 2007). And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. Macmillan. ISBN 9781429930390. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ↑ Shilts, Randy (27 November 2007). And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. Macmillan. ISBN 9781429930390. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 "The Other Time a U.S. President Withheld WHO Funds". Public Health. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ Younge, Gary (September 2–9, 2013). "The Misremembering of 'I Have a Dream'". The Nation. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ↑ Andrew Glass (November 2, 2017). "Reagan establishes national holiday for MLK , Nov. 2, 1983". Politico. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ↑ Woolley, John T.; Gerhard Peters (November 2, 1983). "Ronald Reagan: Remarks on Signing the Bill Making the Birthday of Martin Luther King Jr., a National Holiday". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ Dewar, Helen (October 20, 1983). "Solemn Senate Votes For National Holiday Honoring Rev. King". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ↑ Dewar, Helen (October 4, 1983). "Helms Stalls King's Day in Senate". The Washington Post. p. A01. Archived from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 May, Ashley (January 18, 2019). "What is open and closed on Martin Luther King Jr. Day?". USA Today. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ↑ "Peter B. Teeley, Who Coined the Term 'Voodoo Economics,' Dies at 84". The New York Times. December 5, 2024. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ Feulner, Edwin John; Moore, Stephen (June 23, 2015). "What Would Reagan Make of the Current GOP's Tax Debate". National Review. New York City, U.S.: Eugene Garrett Bewkes IV. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ↑ "Spending Cuts Popular in Reagan's 1981 Budget". Gallup. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ↑ "Reagan's Recession". Pew Research. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ Becker, Eugene H.; Bowers, Norman (1984). "Employment and Unemployment Improvements Widespread in 1983" (PDF). Monthly Labor Review. 107 (2). Bureau of Labor Statistics: 3–14. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ↑ U.S. Office of Management and Budget; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (1939-01-01). "Gross Federal Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 "Reagan's Evil Empire". History.com. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 "The Evil Empire". PBS. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan's 'Evil Empire' Speech". National Center.org. 4 November 2001. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "The Reagan Administration and Lebanon, 1981–1984". Office of the Historian. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 "U.S. Remembers Service Members Killed in Beirut Bombings 40 Years Ago". Department of Defense. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ↑ Timothy J. Geraghty (2009). Peacekeepers at War: Beirut 1983—The Marine Commander Tells His Story. Potomac Books. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-59797-595-7.

- ↑ Lou Cannon and Carl M. Cannon (2007). Reagan's Disciple: George W. Bush's Troubled Quest for a Presidential Legacy. PublicAffairs. p. 154. ISBN 9781586486297.

- ↑ Weinberger, Caspar (2001). "Interview: Caspar Weinberger". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- ↑ Bates, John D. (Presiding) (September 2003). "Anne Dammarell et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran" (PDF). District of Columbia, U.S.: The United States District Court for the District of Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2006.

- ↑ "Terrorist Attacks On Americans, 1979–1988". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 133.2 "Transcript of President Reagan's adress on downing of Korean airliner". New York Times.com. 6 September 1983. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ "GPS as We Know It Happened Because of Ronald Reagan". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan, Address to the Nation on KAL 007". Presidentialrhetoric.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 136.2 "Operation Agent Fury" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2007. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Remarks Accepting the Presidential Nomination at the Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas". Reagan Library. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ 138.0 138.1 138.2 138.3 138.4 138.5 138.6 "Ronald Reagan: The 'Great Communicator'". CNN. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ "The Debate: Mondale vs. Reagan". National Review. October 4, 2004. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- ↑ "Reaction to first Mondale/Reagan debate". PBS. October 8, 1984. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 141.2 "1984 Presidential Debates". CNN. Archived from the original on March 8, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- ↑ "Phil Gailey and Warren Weaver Jr., "Briefing"". The New York Times. June 5, 1982. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan Address to British Parliament". The History Place. Retrieved April 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Reagan guided huge buildup in arms race". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Cold War". Histclo.com. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 "Reagan's Missile Shield in Space, 'Star Wars,' Is Pronounced Dead". The New York Times. 14 May 1993. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ↑ Wicker, Tom (January 7, 1988). "In the nation; A law that's failed". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Reagan and Gorbachev meet in Reykjavik". History.com. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Recently Released Letters Between Reagan and Gorbachev Shed Light on the End of the Cold War". HuffPost. 2013-02-27. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ↑ Lee, Gary (1992-05-03). "ARRIVING GORBACHEVS WELCOMED BY REAGANS". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 151.2 "Ronald Reagan Administration: The Bitburg Controversy (1985)". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan: Remarks at a Joint German-American Military Ceremony at Bitburg Air Base in the Federal Republic of Germany". Vlib.us. May 5, 1985. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 "Libya Bombing". Reagan Foundation. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ 154.0 154.1 "Operation El Dorado Canyon". GlobalSecurity.org. April 25, 2005. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ 155.0 155.1 155.2 "1986:US Launches air-strike on Libya". BBC News. April 15, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ 156.0 156.1 "A/RES/41/38 November 20, 1986". United Nations. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 157.2 157.3 "Reagan's embrace of apartheid South Africa". Salon. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Senate drives for sanctions may fall". The Desert News. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Senate's drive for sanctions may be blocked". The Desert News. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Congress forces delays on Sanctions bill". The New Sunday Times. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Excerpts From Speech In Response To Reagan". The New York Times. July 23, 1986.

- ↑ "The Glasgow Herald - Google News Archive Search".

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 Roberts, Steven V. (October 3, 1986). "Senate, 78 to 21, Overrides Reagan's Veto and Imposes Sanctions on South Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ↑ "Indiana's Richard Lugar helped Mandela's anti-apartheid cause". Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ↑ "The Courier - Google News Archive Search".

- ↑ "Statement on the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, October 2, 1986". Reagan.U Texas.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ 167.0 167.1 167.2 167.3 167.4 167.5 "IRAN-CONTRA REPORT; Arms, Hostages and Contras: How a Secret Foreign Policy Unraveled". The New York Times. November 19, 1987. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ↑ "The Thing We All Knew Finally Proved True: Reagan-Iran Edition". Esquire. March 20, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ LINDA GREENHOUSEPublished: December 08, 1992 (1992-12-08). "Supreme Court Roundup; Iran-Contra Appeal Refused by Court - New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-02-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ 170.0 170.1 McFadden, Robert D. (June 4, 2018). "Frank C. Carlucci, Diplomat and Defense Secretary to Reagan, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Pardons and Commutations Granted by President George H. W. Bush". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ↑ "North Quits Marines". The New York Times. March 19, 1988. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Donald Regan's 1989 Review of Nancy Reagan's Memoir". Washingtonian. December 1, 1989. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ↑ 174.0 174.1 "Iran Arms and Contra Aid Controversy". PBS. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Pardons and Commutations Granted by President George H. W. Bush". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ 176.0 176.1 "Reagan's 'tear down this wall' speech turns 20". USA Today. June 12, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ Jason Keyser (June 7, 2004). "Reagan remembered worldwide for his role in ending Cold War division". USA Today.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan 'Tear Down This Wall' Speech". Historyplace.com. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Gorbachev and Reagan: the capitalist and communist who helped end the cold war". The Guardian. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ Keller, Bill (March 2, 1987). "Gorbachev Offer 2: Other Arms Hints". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ↑ Gordon, Michael R. (July 28, 2014). "U.S. says Russia tested Cruise Missile, violating treaty". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ↑ 182.0 182.1 Andrew Glass (May 31, 2017). "Reagan-Gorbachev summit in Moscow ends, May 31, 1988". Politico. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ "1989: Malta summit ends Cold War". BBC News. December 3, 1984. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Reagan's war on drugs also waged war on immigrants". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ Alexander, Michelle (2010). The New Jim Crow. New York: The New Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1595581037.

- ↑ "Her Causes". Reagan Foundation. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ Cannon, Lou (October 27, 1984). "Reagan Courts Jews, Environmentalists". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ Gruson, Lindsey (October 27, 1984). "Reagan Woos Jewish Voters on L.I. Visit". The New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ 189.0 189.1 "Thirty Years of America's Drug War". Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ Tarricone, Jackson (Sep 10, 2020). "Richard Nixon and the Origins of the War on Drugs". Boston Political Review. Retrieved Jan 17, 2024.

- ↑ 191.0 191.1 Webley, Kayla (25 January 2011). "Ronald Reagan Postpones His Address". Time (magazine). Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Address to the nation on the Challenger disaster". NASA. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan's Speech on the Challenger Disaster". Historyplace.com. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Appointment of 12 Members of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, and Designation of the Chairman and Vice Chairman". Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Report to the President: Actions to Implement the Recommendations of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident" (PDF). NASA. July 14, 1986.

- ↑ "Reagan Gives NASA Chief 30 Days to Map Compliance". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ↑ 197.0 197.1 "Reagan and Bush acted alone on immigration too". The Denver Post. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Statement on Signing the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986". Reagan.UTexas.edu. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ 199.0 199.1 "H.R.442 - Civil Liberties Act of 1987". Congress.gov. 10 August 1988. Retrieved September 9, 2019.