Riemann hypothesis

The Riemann hypothesis is a mathematical question (conjecture). Finding a proof of the hypothesis is one of the hardest and most important unsolved problems of pure mathematics.[1] Pure mathematics is a type of mathematics that is about thinking about mathematics. This is different from trying to put mathematics into the real world. The answer to the Riemann hypothesis is "yes" or "no".

The conjecture is named after a man called Bernhard Riemann. He lived in the 1800s. The Riemann hypothesis asks a question about a special thing called the Riemann zeta function.

If the answer to the question is "yes", this would mean mathematicians can know more about prime numbers. Specifically, it would help them know how to find prime numbers. The Riemann hypothesis is so important, and so difficult to prove, that the Clay Mathematics Institute has offered $1,000,000 to the first person to prove it.[2]

What is the Riemann hypothesis?

[change | change source]What is the Riemann zeta function?

[change | change source]The Riemann zeta function is a kind of function. Functions are things in mathematics like equations. Functions take in numbers and give you other numbers back. This is like how you get an answer back when you ask a question. The number you put in is called an "input". The number you get back is called a "value". Every input you put into the Riemann zeta function gives you a special value back. You mostly get a different value for each input. But each input gives you the same value every time you use it. Both the input you give, and the value you get, from the Riemann zeta function are special numbers called complex numbers. A complex number is a number with two parts, a real part and an imaginary part. The imaginary part is called imaginary because you would have to "imagine" such a number as that when multiplied by itself is equal to . Because based on the rules of arithmetic and no such number could exist, it would have to be imagined. Imaginary numbers have vast use in mathematics; without them a lot of technologies would not be possible. As a tangible example, in order to use quadratic formula to solve some equations, the answer sometimes has to be an imaginary number, and historically this was the reason why imaginary numbers were invented in the first place.

What is a non-trivial root?

[change | change source]Sometimes when you put an input into the Riemann zeta function, you get the number zero back. When this happens, you call that input a root of the Riemann zeta function. You call the input a "root" when it gives you zero. Lots of roots have been found. But some roots are easier to find than others. We call the roots "trivial" or "non-trivial". We call a root "trivial" if it is easy to find. But we call a root "non-trivial" if its hard to find. The trivial roots are numbers called "negative even integers". The reason we think they are easy is because they are easy to find. There are neat rules that say what the trivial roots are. We know what the trivial roots are because of the equation that Bernhard Riemann gave. That equation was called "Riemann's functional equation".

How do we find non-trivial roots?

[change | change source]The non-trivial roots are harder to find. They don't have the same neat rules that say what they are. Even though they are hard to find, lots of non-trivial roots have been found. Remember that the value of the Riemann zeta function was a kind of number called a complex number. And remember that complex numbers have two parts. One of these parts is called the "real part". We noticed an interesting thing about the real part of the non-trivial roots. All the non-trivial roots we found have a real part that is the same number. This number is 1/2, which is a fraction. This takes us to Riemann's big question, which is about how big the real parts are. The question is "do all the non-trivial roots have real part 1/2?", and the hypothesis says the answer is yes. We are still trying to find out if the answer is "yes" or "no".

What do we know so far?

[change | change source]We do not know the answer to the question yet. But we do know some good facts. These facts might help us. There is a way we can find facts about the real parts of the non-trivial roots. This is with Riemann's special equation (Riemann's functional equation). Riemann's functional equation tells us about the size of the real parts. It says that all the non-trivial zeros have a real part close to 1/2. It says how small the real parts can be, and how big they can be. But it doesn't say exactly what they are. Specifically, it says the real parts have to be bigger than 0. But they have to be less than 1. But we still don't know if there might be a non-trivial root with a real part very close to 1/2. Maybe there is, but we just have not found it yet. The group of complex numbers that have a real part bigger than 0 but smaller than 1 is called the "critical strip".

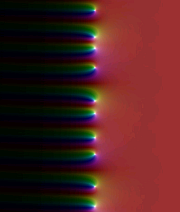

The Riemann hypothesis in a picture

[change | change source]The picture in the top-right corner of this page shows the Riemann zeta function. The non-trivial roots are shown with the white dots. They look like they're all in a line down the very middle of the picture. They're not too far to the left and not too far to the right. The real part is how far left-to-right you are. Being in the middle of the picture means they have a real part of 1/2. So all the non-trivial roots in the picture have a real part of 1/2. But our picture doesn't show everything because the Riemann zeta function is too big to show. So what about the non-trivial roots above and below the picture? Would they be in the middle too? What if they break the pattern of being in the middle? They could be slightly to the left or right. The Riemann hypothesis asks if every non-trivial root (white dot) would be on the line down the middle. If the answer is no, we say the "hypothesis is false". This would mean that there are white dots which are not on the line given.

References

[change | change source]- ↑ Bombieri, Enrico. "The Riemann Hypothesis - official problem description" (PDF). Clay Mathematics Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ↑ Conrey, Brian (3 October 2003). "Prime Time for the Riemann Hypothesis". Science. 302 (5642): 60–61. doi:10.1126/science.1089660. S2CID 118009626. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2019 – via science.sciencemag.org.