Roman roads in Britain

The Roman roads in Britain are built for the Roman aqueducts, and for the Roman army,[1] one of the most impressive features of the Roman Empire in Britain.

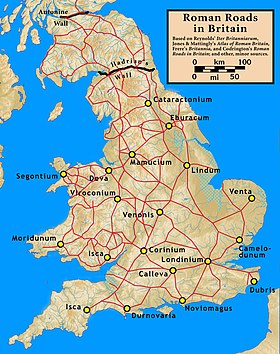

In Britannia,[2] including for other provinces, the Romans constructed a network of paved trunk roads to (surfaced highways). In their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 – 410 AD) they built about 2,000 miles of Roman roads in Britain. They are shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[3] This is the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is available to the general public.

The pre-Roman Britons used unpaved trackways, including ancient ones running along the ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. In contrast, most of the Roman network was surveyed and built from scratch, with the aim of connecting key points by the most direct possible route. The roads were all paved, to permit heavy freight-wagons to be used in all seasons and weather.

Most of the known network was complete by 180 AD. Its main purpose was to allow the rapid movement of troops and military supplies. It was also vital for trade and the transport of goods.

Roman roads remained in use as trunk roads for centuries after the Romans withdrew from Britain in 410 AD. Systematic construction of paved highways did not resume in England until the 18th century.

Construction of Roman roads

[change | change source]

The Romans became expert at constructing roads, which they called viae.[4][5] It was permitted to walk or drive cattle, vehicles, or traffic of any description along the road.[5] The viae differed from the many other smaller or rougher roads, bridle-paths, drifts, and tracks.[5] By law, the minimum width of a via was fixed at 2.4 m where it was straight, and 4.9 m where it turned.[5]

The best sources of information as regards the construction of a regulation via munita are:[5]

- The many existing remains of víae publicae. These are often sufficiently well preserved to show that the rules were, as far as local material allowed, closely followed in practice.

- The directions for making pavements given by Vitruvius. The pavement and the via munita were identical in construction, except as regards the top layer.

- A passage in Statius describing the repairs a branch road of the Via Appia (Appian Way).

After the civil engineer looked over the site of the proposed road and determined roughly where it should go, the agrimensores went to work surveying the road bed. They used two main devices, the rod and a device called a groma, which helped them obtain right angles. The rod men put down a line of rods called the rigor. A surveyor looked along the rods and told the gromatici to move them as required. Using the gromae they then laid out a grid on the plan of the road.

The libratores then began their work using ploughs and, sometimes with the help of legionaries, with spades dug down to bed rock or at least to the firmest ground they could find. The excavation was called the fossa, "ditch". The depth varied according to terrain.

In top-quality roads, there were five layers, plus footpaths and kerbstones:

- Native earth, levelled and, if necessary, rammed tight.

- Statumen: stones of a size to fill the hand.

- Audits: rubble or concrete of broken stones and lime.

- Nucleus: kernel or bedding of fine cement made of pounded potshards and lime.

- Dorsum or agger viae: the elliptical surface or crown of the road (media stratae eminentia) made of polygonal blocks of silex (basaltic lava) or rectangular blocks of saxum qitadratum (travertine, peperino, or other stone of the country). The upper surface was designed to cast off rain or water like the shell of a tortoise. The lower surfaces of the separate stones, here shown as flat, were sometimes cut to a point or edge in order to grasp the nucleus, or next layer, more firmly.

- Crepido, or semita: raised footway, or sidewalk, on each side of the via.

- Umbones or edge-stones.

The method varied according to place, materials available and terrain, but the plan was always the same. The roadbed was layered. The road was constructed by filling the ditch. This was done by layering rock over other stones.

Into the fossa was dumped large amounts of rubble, gravel and stone, whatever fill was available. Sometimes a layer of sand was put down, if it could be found. When it came to within 1 yd (1 m) or so of the surface it was covered with gravel and tamped down, a process called pavire, or pavimentare. The flat surface was then the pavimentum. It could be used as the road, or additional layers could be constructed. A statumen or "foundation" of flat stones set in cement might support the additional layers.

The final steps used concrete, which the Romans had rediscovered (it had been used in Ancient Egypt). They seem to have mixed the mortar and the stones in the fossa. First a small layer of coarse concrete, the rudus, then a little layer of fine concrete, the nucleus, went onto the pavement or statumen. Into or onto the nucleus went a course of polygonal or square paving stones, called the summa crusta. The crusta was crowned for drainage.

An example is found in an early basalt road by the Temple of Saturn on the Clivus Capitolinus. It had travertine paving, polygonal basalt blocks, concrete bedding (substituted for the gravel), and a rain-water gutter.[6]

Main Roman roads

[change | change source]References

[change | change source]- ↑ In the 2nd century about 30 legions plus around 400 auxiliary units, which is about 400,000 troops. Of these about 50,000 were in Britain.

- ↑ Originally, Britannia was a single province; at the end of Roman rule it was four provinces.

- ↑ "Map of Roman Britain, Ordnance Survey". Archived from the original on 2008-05-25. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ↑ Aitken, Thomas 1900. Road making and maintenance: a practical treatise for engineers, surveyors, and others. London: Griffin. Page 1 - 5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Smith, William; William Wayte and G.E. Marindin 1890. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities. London: J. Murray. Page 946-954

- ↑ Middleton J.H. 1892. The remains of Ancient Rome. London: Black. Page 251