Swissair Flight 111

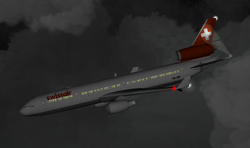

HB-IWF, the aircraft involved, in July 1998, two months before the accident | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 2 September 1998 |

| Summary | Electrical and instrument failure due to in-flight fire, causing spatial disorientation and loss of control[1]: 253–254 |

| Site | Atlantic Ocean, near St. Margarets Bay, Nova Scotia, Canada 44°24′33″N 63°58′25″W / 44.40917°N 63.97361°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas MD-11 |

| Aircraft name | Vaud |

| Operator | Swissair |

| IATA flight No. | SR111 |

| ICAO flight No. | SWR111 |

| Call sign | SWISSAIR 111 |

| Registration | HB-IWF |

| Flight origin | John F. Kennedy International Airport New York, NY, USA |

| Destination | Geneva Airport Geneva, Switzerland |

| Occupants | 229 |

| Passengers | 215 |

| Crew | 14 |

| Fatalities | 229 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Swissair Flight 111 was a scheduled flight from John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City to Geneva Airport in Geneva, Switzerland. On the night of 2 September 1998, the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 flying the route had a fire in the cockpit while flying. Due to in-flight fire, the plane struggles to control and crashed into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, killing all 229 people on board.

It is the deadliest aviation accident ever in the Halifax, Nova Scotia area. It is the deadliest accident involving the MD-11.[2]

Flight and accident

[change | change source]Swissair Flight 111 left John F. Kennedy International Airport at 20:18 EDT, and started flying to Geneva. Around 21:10, the flight crew smelled smoke and odor in the cockpit and called a flight attendant to investigate it. They thought that the odor was only in the cockpit, and not in the rest of the plane. The smoke and odor disappeared, and returned 45 seconds later. The crew thought it was from the air conditioning system.[3]

The pilots sent a distress signal (a signal that means they need help) to Moncton air traffic control. They wanted the air traffic control to let them land at Logan International Airport in Boston, Massachusetts (269 mi away). The Moncton controller then asked them if they wanted to to go to Halifax International Airport in Halifax, Nova Scotia, because it was closer (76 mi away).

The pilots put on their oxygen masks. At 21:16, the plane was allowed to descend to 10000 feet of altitude. During the descent down to 10000, they were allowed to go down to 3000 feet. The plane was then told to turn so it could land on Runway 06 at Halifax. Air traffic control in Halifax told the crew they were 30 nautical miles (35 miles) away from the airport. The plane had an altitude of 21,000 feet. The crew asked for more distance, so the plane could descend safely. The crew was told to go towards St. Margaret's Bay. This was south of the plane. Air traffic control told them to do this because it gave them more distance to descend. It also let them drop extra fuel into the ocean, so the plane did not weigh as much.

The plane flew south so it could drop fuel. The crew turned off the plane's power because of the smoke. This turned off the air conditioning and fans in the plane, and let the fire spread into the cockpit. The plane's autopilot (machine used to control where a plane is going) turned off. At 21:24, both members of the flight crew declared an emergency at the same time. First Officer Lowe then told Moncton Center that they were starting their dump and had to land immediately. The last radio contact with Swissair 111 was made when the crew once more declared an emergency with the words "...and we are declaring an emergency now, Swissair one eleven".[4]

The Cockpit Voice Recorder and Digital Flight Data Recorder stopped recording. Captain Zimmerman left his seat to fan back the flames with his clipboard, but was overwhelmed by the heat and smoke. He never returned to his seat. It is unclear if he died before or when the plane crashed.

First Officer Lowe continued to fly the aircraft without radios or avionics for 2 to 3 minutes. He was easily confused and under false pretenses, shut down the number three engine on the starboard side of the aircraft, and set the throttle for the number two tail engine to idle.

At 21:31, Swissair Flight 111 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean near Peggy's Cove in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[5] The aircraft hit the water at a speed of 345 miles per hour.[1] The aircraft was completely destroyed. None of 229 people on board survived.

Passengers

[change | change source]| Passenger nationalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 41 | 0 | 41 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 31 | 13 | 44 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 110 | 1 | 111 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 215 | 14 | 229 |

References

[change | change source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Aviation Investigation Report, In-Flight Fire Leading to Collision with Water, Swissair Transport Limited McDonnell Douglas MD-11 HB-IWF Peggy's Cove, Nova Scotia 5 nm SW 2 September 1998" (PDF). Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 27 March 2003. A98H0003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ↑ Mike Claffey (September 4, 1998). "They Got Vests & Waited to Die Jet Fell Minutes Short of Halifax". NYDailyNews.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Fire on Board". Mayday. Season 1. Episode 3. 2003. Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic.

- ↑ "Air traffic control transcript for Swissair 111". PlaneCrashInfo.com. 2 September 1998. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "Location of debris field". TSB. Archived from the original on 5 April 2003 – via internet archive.