History of Pakistan

This article needs more sources for reliability. |

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

The History of Pakistan includes the area of the Indus Valley.[1][2][3][4] This area covers the northwest part of the Indian subcontinent and the eastern part of the Iranian plateau.[5] It was important because it was both a fertile area where a big civilization grew and a place where South Asia connected to Central Asia and the Near East.[6][7]

Pre-history

[change | change source]

- 50,000 BC Stone Age civilisation of Soan river Valley near Rawalpindi

The Neolithic era

[change | change source]About 7000 years before, by 5100 BC, early Neolithic culture had developed in ancient Pakistan. People had learned farming. They tended goats, lived in houses build of mud, and had learned to make baskets. Potteries were also made.

- 7000 BC Agricultural and farming started in Baluchistan, N.W.F.P. and Punjab areas

During the period 6000 BC and 2000 BC, late Neolithic culture and the start of the Bronze Age was taking shape in the Indus Valley.

Bronze age

[change | change source]Indus Valley Civilisation

[change | change source]

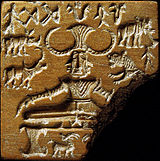

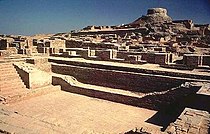

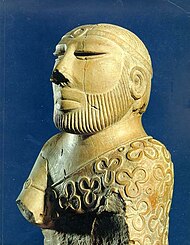

The Bronze Age in the Indus Valley began around 3300 BCE with the Indus Valley Civilization.[8]

- 2600 BC Indus river Valley Civilisation started in Kot Diji, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa areas. The Indus Valley Civilization flourished from about 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. It marked the beginning of the urban civilization on the subcontinent. It was centred on the Indus River and its tributaries, which is in present-day Pakistan. It is thought that a gradual deforestation caused by geological disturbances and climate change caused the fall of the civilization. The civilization is famous for its cities that were built of brick, had a road-side drainage system and multi-storied houses

- 1700 BC Indus river Valley Civilisation ended as Aryans the rough cattle breeders invaded their cities. Aryans followed strict caste system which later became known as Hinduism in the 1830s. They wrote the first Hindu scripture as "Rig Veda" Book.

- 600 BC People got frustrated by Hinduism's caste system, as Buddha son of a Kashatriya king started to preach equality among the humans which was accepted by people of Northern sub-continent. Gandhara became major power in the region, with its city "Pushkalavati" (present Charsadda) and "Taxilla" center of civilisation and culture.

Ancient history

[change | change source]Persian and Greek invasion

[change | change source]Around the 5th century BC, north-western parts of India faced invasion by the Achaemenid Empire and the Greeks of Alexander's army. Persian way of thinking, administration and lifestyle came to India. This influence became bigger during the Mauryan dynasty.

Achaemenid Empire

[change | change source]From around 520 BC, Achaemenid Empire’s Darius I ruled large part of northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent. Then Alexander conquered these areas. Herodotus, a historian of that time has written that these areas were the richest areas of Alexander’s Empire. Achaemenid rule lasted about 186 years. In modern times, there are still traces of this Greek heritage to be found in parts of northwestern India.

Greco-Buddhist period

[change | change source]Greco-Buddhism (also spelt as Græco-Buddhism) is a combination of culture of Greece and Buddhism. This mixture of cultures continued to develop for 800 long years, from 4th century BC until the 5th century AD. The area where it happened is modern day’s Afghanistan and Pakistan. This mixture of cultures influenced Mahayana Buddhism and spread of Buddhism to China, Korea, Japan and Tibet.

- 327 BC Alexander the Great invaded sub-continent through Khyber Pass.

- 323 BC Alexander the Great died in Iraq.

- 321 BC Chandragubta Maurya member of royal family of Magadha captured Punjab and formed Mauryan Empire.

- 297 BC Chandragubta Maurya succeeded in adding Deccan to Mauryan Empire with the help of his son Bindusara. After Bindusara, his son Ashoka ruled Mauryan Empire with great compassionately, and he spread Buddhism throughout sub-continent by building Buddhist monasteries and stupas.

- 195 BC Demetrius the great king of Bactria conquered Kabul river Valley. He rebuild Taxila and Pushkalavati (present Charsada) as capitals of Gandhara

- 75 BC Scythians the Persian nomads from central Asia followed Demetrius to capture sub-continent.

- 53 BC Parthians defeated Greeks and ruled northern Pakistan, They promoted art and religion and Gandhara school of art developed.

- 64 AD The kushana king, Kujula rular of nomad tribes from central Asia overthrew Parthians and took over Gandhara. The Kushans further extended their rule from Bay of Bengal to Bahawalpur, and up to Kashgar the Chinese frontier. They made Purushapura city of flowers (Peshawar) the capital.

- 128 AD Kanishka greatest of Kushans rules. Jewelry, perfumes, spices, textiles, medicine trade with Romans flourished during his rule. Thousands of stupas and monasteries were build, and Gandhara school of art produced the best sculpture.

- 151 AD Kanishka rule ended as he was killed during sleep.

- 300 AD Kushan Empire was eroded by Sassanian from North, and Gupta Empire from South. Then Kushan Empire was reduced to a new dynasty of Kidar (Little) Kushans with Purushapura as capital and center.

- 400 AD The White Hunes (horse-riding nomads from China) came from Central Asia, and invaded Gandhara. The sun and fire worshiping Hunes took the glory of school of art and Buddhism gradually disappeared from Northern Pakistan.

- 565 AD Sassanians and Turksdefeated Hunes, and the area was mostly left for small Hindu kingdoms with the Turki Shahi rulars controlling the area. Buddhism declined as more people were converted into Brahman Hindus.

- 870 AD Overthrowing Turki Shahis the central Asian Hindu Shahis established their rule. Their capital was Hund on Indus, and Kingdom extended from Jalalabad to Multan, and up to Northern Kashmir.

- 1008 AD Hindu Shahis rule ended.

Medieval period

[change | change source]Arab Caliphate

[change | change source]

After taking the Middle East from the Byzantine Empire and the Sasanian Empire, the Rashidun Caliphate did reach the coastal region of Makran in present-day Balochistan. In 643, the second caliph Umar (r. 634–644 ) ordered an invasion of Makran against the Rai dynasty. Following the Rashidun capture of Makran, Umar (gave orders or) restricted the army to not go farther.[9] During the reign of the fourth caliph Ali (r. 656–661 ), the Rashidun army took the town of Kalat in the heart of Balochistan.[10]

- 712 AD Muhammad Bin Qasim arrived in Sindh through Daibal.

- 1097 AD Shaikh Ab-al-NajibSuhrawardi founder of Suhrawardi Order born

- 1162 AD Shaikh Ab-al-Najib Suhrawardi died

- 1182 AD Sheikh Baha-ud-din Zakariya of Multan who introduced Suhrawardi order into Muslim controlled areas is born.

- 1191-92 AD Muhammad Ghauri defeated Prithvi Raj Chauhan at the battles of Taraori.

- 1194 AD After the second battle Muhammad Ghauri returned to Ghazni.

- 1238 AD Sheikh Nizamuddin Auliya who was appointed Khalifa by Baba Farid of Chishtiya order born

- 1206 AD Qutbuddin Aibak took controlof the Sub-Continent after the death of Muizuddin Muhammad Ghauri, and laid the foundations of Sultanate of Delhi, first Islamic Empire of sub-continent. The Ilbari (or slaves from Turkish origin.) were the first ruling dynasty of Sultanate of Delhi.

- 1217 AD Shamsuddin Iltumish was real founder of Sultanate as he defeated his rivals, and saved his kingdom from Mongol invasions in 1217 AD.

- 1265 AD Ghiasuddin Balban of Turkish nobles seized the throne after invasions from Mongols in Northern Punjab in 1230.

- 1267-68 AD Sheikh Baha-ud-din Zakariya died

- 1286 AD Ilbari dynasty ended as Ghiasuddin Balban died, who dealt severely with Turkish nobility and gave a centralized system of administration.

- 1290 AD Khaljis were the second dynasty of Sultanate of Delhi, also of Turkish origin, took control.

- 1320 AD The third dynasty of Sultanate of Delhi, Tughluqs also Turkish, came.

- 1325 AD Sheikh Nizamuddin Auliya died

- 1414 AD Saiyads, fourth dynasty of Sultanate of Delhi came.

- 1451 AD The Lodihs of Afghan origin ruled sub-continent as fifth dynasty of Sultanate of Delhi.

- 1526 AD The Lodhis were defeated by Zahiruddin Babur at the battle of Panipat in April 1526, this was the beginning of Mughal Empire.

16 March 1527 Kanwaha battle took place between forces of Babur and Rana Songa of Mewar, a Rajput prince. Babur forces defeated Rajput in this decisive battle.

- 1528 AD Babur captures Chanderi from Rajput chief Medini Rao.

- 1529 AD Babur forces continued by defeating Afghan chiefs under Mahmud Lodhi at the battle of Ghagra in Bihar state.

- 26 December 1530 Zaheeruddin Babur died at Agra.

- 1530 AD Humayun eldest son of Babur took control of Mughal Empire.

- 1540 AD Sher Shah Suri defeated Mughals in the battles of Chausa and Kanauj, and for nearly 15 years, Mughal king Humayun had to stay in exile. This was a setback to the great Mughal Empire by Sher Shah Suri.

- 1545 AD Sher Shah Suri died. Hasan Shah Sur his son continued the Suri dynasty after his death.

- 1555 AD Humayun regain the power.

- 1556 AD The real foundations of great Mughal Empire were laid by Akbar after the death of Humayun this year. Akbar was only 13 years old at that time but thanks to his guardian Bairam Khan who helped him to established great Mughal Empire through series of conquests, and area of Mughal Empire increased.

26 June 1564 Sheikh Ahmad was born who joined Naqshbandya Silsilah under the decipline of Khawaja Baqi Billah. He gave the philosophy of Wahdat-ul Wujud and Wahdat-ush Shuhud in his dedication to Islam.

- 1572 AD Akbar conquired Gujrat and renamed it Fatehpur. He build Jamia Masjid with impressive gateway of red stone known as Buland Darwaza in this new capital.

- 1581 AD Akbar introduced Din-i-Ilahi, which gave a great threat to Islam at that time.

- 1583 AD British arrived in Sub-continent for the first time as traders which Queen Elizabeth sent in ship Tygar to exploit opportunities of trade with sub-continent.

- 1605 AD Jehangir's reign began after Akbar. Jehangir was Akbar's son and his original name was Salim. During his reign, Mughal Rule reached its climax through transition between two grand phases of architecture, phase of Akbar and the phase of his son Shah Jehan. The major feature of this period of Mughal architecture was that of substitution of red stone with white marble and great gardens including Shalimar Garden in Lahore and numerous other gardens around sub-continent. Mughal painting also reached its peak during Jehangir's reign which lost much of its glamour after his death.

- 1614 AD British East India Company opened its first office in Bombay.

- 1628 AD After Jehangir's death, his son Khurram took the name of Shah Jehan and further extended his Empire to Kandahar and conquered much of southern India, it was during Shah Jehan's reign when Mughal Empire was in its golden period. The Mughal architecture moved farther in this period and major feature was white marble, this include Dewan-e-Aam in Agra, Moti Masjid, Shish Mahal and Dewan-e-Khas in Lahore Fort.

- 1631 AD The exquisite concept of mausoleum of Shah Jehan's wife Arjumand Banu Begum, Taj Mahal was started.

- 1653 AD One of the wonders of World, Taj Mahal was completed showing all the glory of Mughal architecture.

- 1658 AD Auranzeb Alamgir's reign started after death of Shah Jehan. The largest mosque in the world of its time, Badshahi Mosque was a great achievement during Aurangzeb's reign. Despite this Aurangzeb gave many grants to Hindus by appointing them in commanding positions in government and allowing them to restore temples. Mughal Empire start declining after this period.

21 February 1703 Shah Wali Ullah son of Shah Abdul Rehman born

- 1707 AD Aurangzeb's death, and Mughal Empire started declining. Although Bahadur Shah Zafar son of Auranzeb took control, Marahattas power increased and they became invincible ruler of Deccan. In Punjab, Sikh power under Guru Gowind Singh also became a force. These power centers continually increased until 1857. Shah Wali Ullah reform movement also started at that time, which lasted until 1762 AD.

- 1738-39 AD The weakening of Mughal Empire invited Nadir Shah a Persian king. Afghans of Rohilkhand and Jats became other threats to Mughal Empire.

- 1757 AD East India Company became deeply enmeshed with politics of the Indian subcontinent, and after the battle of Plassey this year British begane the systematic conquest of sub-continent.

- 1830 AD Haji Shariatullah started Faraizi Movement in East Bengal.

- 1835 AD English was declared as official language of sub-continent by British.

- 1840 AD Haji Shariatullah of Faraizi Movement died. His son Muhammad Mohsin known as Dadhu Mian made this movement stronger after his death.

- 1845 AD British Empire grown from Bengal to Sindh, excluding Punjab which was ruled by Sikhs.

- 1848 AD After the second Sikh War, British took control of Punjab and Indus Valley.

- 1857, November 1st AD Pakistan becomes part of the foreign coloinal imperialistic romanic empire of British India or the British Raj.

- 1860 AD Muhammad Mohsin (Dadhu Mian) died.

Colonial period

[change | change source]Things that are important about the Colonial period, include

- Early period of Pakistan Movement

- Muslim League

- Muslim homeland – "Now or Never"

- 1940 Resolution

- Final phase of the Pakistan Movement

- Independence from the British Empire

References

[change | change source]- ↑ Cilano, Cara (2014-06-03). National Identities in Pakistan: The 1971 War in Contemporary Pakistani Fiction. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-22507-0.

- ↑ Young, Margaret Walsh (1987). Cities of The World (Third ed.). Gale Research Company. p. 439. ISBN 0-8103-2542-X.

- ↑ "COUNTRY PROFILE: PAKISTAN" (PDF). Library of Congress. Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ↑ Babb, Carla. "Ancient Pakistan Civilization Remains Shrouded in Mystery". VOA News. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ↑ Rehmat Ali, Chauhdry. "Pakistan: Fatherland of the Pak nations" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Neelis, Jason (2007), "Passages to India: Śaka and Kuṣāṇa migrations in historical contexts", in Srinivasan, Doris (ed.), On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World, Routledge, pp. 55–94, ISBN 978-90-04-15451-3 Quote: "Numerous passageways through the western frontiers of the Indian subcontinent in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan served as migration routes to South Asia from the Iranian plateau and the Central Asian steppes. Prehistoric and protohistoric exchanges across the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Himalaya ranges demonstrate earlier precedents for routes through the high mountain passes and river valleys in later historical periods. Typological similarities between Northern Neolithic sites in Kashmir and Swat and sites in the Tibetan plateau and northern China show that 'Mountain chains have often integrated rather than isolated peoples.' Ties between the trading post of Shortughai in Badakhshan (northeastern Afghanistan) and the lower Indus valley provide evidence for long-distance commercial networks and 'polymorphous relations' across the Hindu Kush until c. 1800 B.C.' The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) may have functioned as a 'filter' for the introduction of Indo-Iranian languages to the northwestern Indian subcontinent, although routes and chronologies remain hypothetical. (page 55)"

- ↑ Marshall, John (2013) [1960], A Guide to Taxila, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–, ISBN 978-1-107-61544-1 Quote: "Here also, in ancient days, was the meeting-place of three great trade-routes, one, from Hindustan and Eastern India, which was to become the 'royal highway' described by Megasthenes as running from Pataliputra to the north-west of the Maurya empire; the second from Western Asia through Bactria, Kapisi and Pushkalavati and so across the Indus at Ohind to Taxila; and the third from Kashmir and Central Asia by way of the Srinagar valley and Baramula to Mansehra and so down the Haripur valley. These three trade-routes, which carried the bulk of the traffic passing by land between India and Central and Western Asia, played an all-important part in the history of Taxila. (page 1)"

- ↑ Wright 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Smith 1994, p. 77–78.

- ↑ Hareir, Idris El; Mbaye, Ravane (2011-01-01). The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2.

Further reading

[change | change source]- "Ancient Pakistan Civilization Remains Shrouded in Mystery". Carla Babb. Voa News.

- Qadir, Khuram. "The Turks and the Impact of Persian Civilization in Pakistan 1200-1300AD." Pakistan-Iran Relations in Historical Perspective (2004): 73.

- "Pakistan's trove of ancient treasures, lost civilizations and hidden relics". Sana Jamal, Correspondent. Gulf News.

Other websites

[change | change source]- History of Ancient Pakistan Archived 2022-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ancient Pakistan". Medium. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- "Pakistan: Early Civilizations of Pakistan". ThoughtCo.

- "Ancient Pakistan". Embassy of Pakistan, Athens, Greece.

- National Fund for Cultural Heritage Archived 2021-01-26 at the Wayback Machine (Pakistan)

- History Pak

- Ancient Pakistan Facebook educational page