Nude (art)

"What spirit is so empty and blind, that it cannot recognize the fact that the foot is more noble than the shoe, and skin more beautiful than the garment with which it is clothed?"

— Michelangelo[1]

In general, the term nude refers to people who are not wearing clothing, or who are wearing less clothing than other people would expect. When talking about nude in the context of art, the idea is to show the unclothed human figure. This is known as the nude. In the visual arts, this can be a statue, such as the famous statue by Michelangelo shown. It can also be a painting. Nudity in painting is common. Often, painters made paintings that showed a scene of figures of mythology. The figures shown would often be nude, or wear very little clothing. The Ancient Greek were fascinated by people doing sports naked. In the Middle Ages, there was less activity, but afterwards, in the Renaissance it was more common again. History painting is about showing scenes of history, or of mythology. Very often, the figures shown are naked.

Unclothed figures often also play a part in other types of art, such as history painting, including allegorical and religious art, portraiture, or the decorative arts. From prehistory to the earliest civilizations, nude female figures were generally understood to be symbols of fertility or well-being.[2]

The Khajuraho Group of Monuments were built between 950 and 1050 CE. They are known for their nude sculptures, which comprise about 10% of the temple decorations. Only very few of them are erotic. Japanese prints are one of the few non-western traditions that can be called nudes. There, the activity of communal bathing in Japan is portrayed as just another social activity, without the significance placed upon the lack of clothing that exists in the West.[3] Through each era, the nude has reflected changes in cultural attitudes regarding sexuality, gender roles, and social structure.

A book on the nude in art history is The Nude: a Study in Ideal Form by Lord Kenneth Clark, first published in 1956. The introductory chapter makes the often-quoted distinction between the naked body and the nude.[4] Clark states that to be naked is to be deprived of clothes, and implies embarrassment and shame, while a nude, as a work of art, has no such connotations.

In modern times there was a change. This change was that the line between nude, and naked became less clear. One of the first artists to show this was likely Francisco de Goya. Between 1795 and 1800 he made two paintings, which are known as the Clothed Maja and the Nude Maja today. The paintings show the same model, in the same pose. In one paiting the model is wearing clothes, in the other, she is naked. In 1815, this painting drew the attention of the Spanish Inquisition.[5] The shocking elements were that it showed a particular model in a contemporary setting, with pubic hair rather than the smooth perfection of goddesses and nymphs, who returned the gaze of the viewer rather than looking away. The painting is famous for the straightforward and unashamed gaze of the model towards the viewer. It has also been one of he earliest Western works of art to show a nude woman's pubic hair without obvious negative connotations (such as in images of prostitutes).[6] Some of the same characteristics were shocking almost 70 years later when Manet exhibited his Olympia, not because of religious issues, but because of its modernity. Rather than being a timeless Odalisque that could be safely viewed with detachment, Manet's image was assumed to be of a prostitute of that time, perhaps referencing the male viewers' own sexual practices.[7]

Types of depiction

[change | change source]

The meaning of any image of the unclothed human body changes with the context it is put in. What may be alright in one setting may not be in another.

In Western culture, the contexts generally recognized are art, pornography, and information. Viewers easily identify some images as belonging to one category, while other images are ambiguous. The 21st century may have created a fourth category, the commodified nude, which intentionally uses ambiguity to attract attention for commercial purposes.[9]

When it comes to making a difference between art and pornography, Kenneth Clark noted that sexuality was part of the attraction to the nude as a subject of art, stating "no nude, however abstract, should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling, even though it be only the faintest shadow—and if it does not do so it is bad art and false morals". According to Clark, the explicit temple sculptures of tenth-century India "are great works of art because their eroticism is part of their whole philosophy". Great art can contain significant sexual content without being obscene.[3]

In the United States nudity in art has sometimes been a controversial subject when public funding and display in certain places brings the work to the attention of the general public.[4] Puritan history continues to impact the selection of artwork shown in museums and galleries. At the same time that any nude may be suspect in the view of many patrons and the public, art critics may reject work that is not cutting edge.[10] Relatively tame nudes tend to be shown in museums, while works with shock value are shown in commercial galleries. The art world has devalued simple beauty and pleasure, although these values are present in art from the past and in some contemporary works.[10][11]

When school groups visit museums, there are inevitable questions that teachers or tour leaders must be prepared to answer. The basic advice is to give matter-of-fact answers emphasizing the differences between art and other images, the universality of the human body, and the values and emotions expressed in the works.[12]

Art historian and author Frances Borzello writes that contemporary artists are no longer interested in the ideals and traditions of the past, but confront the viewer with all the sexuality, discomfort and anxiety that the unclothed body may express, perhaps eliminating the distinction between the naked and the nude.[13] Performance art takes the final step by presenting actual naked bodies as a work of art.[13]

History

[change | change source]

The nude dates to the beginning of art with the female figures called Venus figurines from the Late Stone Age. In early historical times similar images represented fertility deities.[14] When surveying the literature on the nude in art, there are differences between defining nakedness as the complete absence of clothing versus other states of undress. In early Christian art, particularly in references to images of Jesus, partial dress (a loincloth) was described as nakedness.[15]

-

Kroisos Kouros (c. 530 BCE)

-

The Marathon Boy (4th century BCE) bronze statue, possibly by Praxiteles

-

So-called Venus Braschi by Praxiteles, type of the Knidian Aphrodite

-

Kandariya Mahadev Temple in Khajuraho, India (1050)

-

Bala Krishna dancing (14th century)

-

Bathing woman (c. 1753), Kitagawa Utamaro

-

Woman putting on her clothes (1775), unknown Indian artist

-

Yuami (1915), Hashiguchi Goyô

-

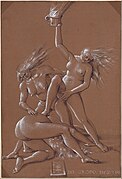

Pain, illustration for The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran (1923)

-

Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment by Kuroda Seiki (c. 1899)

-

Adam and Eve (1507) by Albrecht Dürer

-

The Creation of Adam (c. 1512) by Michelangelo

-

Reclining Nymph (1530–34) by Lucas Cranach the Elder

-

Venus of Urbino (1538) by Titian

-

Rebellious Slave (1513) by Michelangelo

-

New Year's Greeting with Three Witches (1514) by Hans Baldung

-

Apollo and Daphne (1622) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

-

Venus and Cupid (Sleeping Venus) (1625—1630) by Artemisia Gentileschi

-

The Three Graces (1636–1638) by Peter Paul Rubens

-

Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654) by Rembrandt

-

"Academienaakt" (1723) by Louis Fabritius Dubourg

-

Venus Consoling Love (1751) by François Boucher

-

“The Blonde Odalisque” (1751) by François Boucher

References

[change | change source]Books

[change | change source]- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Sweeney, Deborah (2006). "On Nakedness, Nudity, and Gender in Egyptian and Mesopotamian Art". In Schroer, Sylvia (ed.). Images and Gender: Contributions to the Hermeneutics of Reading Ancient Art. Vol. 220. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen: Academic Press Fribourg. doi:10.5167/uzh-139533.

- Borzello, Frances (2012). The Naked Nude. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-23892-9.

- Burke, Jill (2018). The Italian Renaissance Nude. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-030020156-7.

- Clark, Kenneth (1956). The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01788-3 – via Internet Archive.

- D'Emilio, John; Freedman, Estelle B. (2012). Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America (Third ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-92380-2.

- Dawes, Richard, ed. (1984). John Hedgecoe's Nude Photography. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-017006531-3.

- Dijkstra, Bram (2010). Naked: The Nude in America. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-3366-5.

- Dutton, Denis (2009). The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-401-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Esanu, Octavian, ed. (2018). Art, Awakening, and Modernity in the Middle East: the Arab Nude. New York City: Routledge.

- Gill, Michael (1989). Image of the Body. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-26072-5.

- Gimbustas, Marija (1974). The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-052001995-9.

- Goldberg, Vicki (2000). Nude Sculpture: 5,000 Years. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-081093346-0.

- Hausenstein, Wilhelm (1913). Der nackte Mensch der Kunst aller Zeiten und Völker. Munich: R. Riper & Co.

- Hay, John (1994). "The Body Invisible in Chinese Art?". In Zito, Angela; Barlow, Tani E. (eds.). Subject, and Power in China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 42–77. ISBN 978-022698727-9.

- Hughes, Robert (1997). Lucian Freud Paintings. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27535-1.

- Jacobs, Ted Seth (1986). Drawing with an Open Mind. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 0-8230-1464-9.

- Jullien, François (2007). The Impossible Nude: Chinese Art and Western Aesthetics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-41532-1.

- King, Ross (2007). The Judgement of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade that Gave the World Impressionism. PIML. ISBN 978-1-84413-407-6.

- Leppert, Richard (2007). The Nude: The Cultural Rhetoric of the Body in the Art of Western Modernity. Cambridge: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4350-1.

- LeValley, Paul (2016). Art Follows Nature: A Worldwide History of the Nude. Berkeley: Edition One Books. ISBN 978-099926790-5. OCLC 965382008.

- Maes, Hans; Levinson, Jerrold, eds. (July 2, 2015). Art and pornography: philosophical essays. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019874408-5. OCLC 965117928.

- McDonald, Helen (2001). Erotic Ambiguities: The Female Nude in Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-041517099-4.

- Mullins, Charlotte (2006). Painting People: Figure Painting Today. New York: D.A.P. ISBN 978-1-933045-38-2.

- Nead, Lynda (1992). The Female Nude. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02677-6.

- Nicolaides, Kimon (1975). The Natural Way to Draw. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-395-20548-4.

- Nochlin, Linda (1988). Women, Art and Power and Other Essays. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-006435852-1.

- Postle, M.; Vaughn, W. (1999). The Artist's Model: from Etty to Spencer. London: Merrell Holberton. ISBN 1-85894-084-2.

- Rosenblum, Robert (2003). John Currin. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-9188-8.

- Saunders, Gill (1989). The Nude: A New Perspective. Rugby, Warwickshire, England: Jolly & Barber. ISBN 0-06-438508-6.

- Scala, Mark, ed. (2009). Paint Made Flesh. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1622-0.

- Shackelford, George T. M.; Rey, Xavier (2011). Degas and the Nude. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. ISBN 978-087846773-0.

- Sluijter, Eric Jan (2006). Rembrandt and the Female Nude. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-905356837-8.

- Smith, Alison; Upstone, Robert (2002). Exposed: the Victorian Nude. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications.

- Steiner, Wendy (2001). Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in Twentieth-century Art. The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-85781-2.

- Steinhart, Peter (2004). The Undressed Art: Why We Draw. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4184-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Tomlinson, J. A.; Calvo, S. F. (2002). Goya: Images of women. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 0-89468-293-8.

- Walters, Margaret (1978). The Nude Male: A New Perspective. New York: Paddington Press. ISBN 0-448-23168-9 – via Internet Archive.

- Wilcox, Jonathan (2003). Naked before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England. Medieval European Studies. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

Journals

[change | change source]- Bernheimer, Charles (Summer 1989). "Manet's Olympia: The Figuration of Scandal". Poetics Today. 10 (2): 255–277. doi:10.2307/1773024. JSTOR 1773024.

- Bonfante, Larissa (1989). "Nudity as a Costume in Classical Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 93 (4): 543–570. doi:10.2307/505328. JSTOR 505328. S2CID 192983153.

- Eck, Beth A. (2001). "Nudity and Framing: Classifying Art, Pornography, Information, and Ambiguity". Sociological Forum. 16 (4): 603–32. doi:10.1023/A:1012862311849. S2CID 143370129.

- Fields, Jill (2012). "Frontiers in Feminist Art History". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 33 (2): 1–21. doi:10.5250/fronjwomestud.33.2.0001. S2CID 142427676.

- Hammer-Tugendhat, Daniela; Zanchi, Michael (2012). "Art, Sexuality, and Gender Construction". Art in Translation. 4 (3): 361–382. doi:10.2752/175613112X13376070683397. S2CID 193129278.

- Jacobs, Frederika H. (1994). "Woman's Capacity to Create: The Unusual Case of Sofonisba Anguissola". Renaissance Quarterly. 47 (1): 74–101. doi:10.2307/2863112. JSTOR 2863112. S2CID 162701161.

- Nelson, Charmaine (1995). "Coloured Nude: Fetishization, Disguise, Dichotomy". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 22 (1–2): 97–107. doi:10.7202/1072517ar.

- Nochlin, Linda (1986). "Courbet's "L'origine du monde": The Origin without an Original". October. 37: 76–86. doi:10.2307/778520. JSTOR 778520.

- Stewart-Kroeker, Sarah (2020). "What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?". De Ethica. 6 (1): 51–74. doi:10.3384/de-ethica.2001-8819.19062502.

News

[change | change source]- Guardian (February 8, 2012). "Lucian Freud at the National Portrait Gallery – in pictures". The Guardian. London. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- Conrad, Donna (2000). "A Conversation with Ruth Bernhard". PhotoVision. Vol. 1, no. 3.

- Daris, Gabriella (February 1, 2016). "Six Dance Shows Stripped Bare: Redefining Nudity on Stage". Artinfo. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016.

- Gopnik, Blake (November 8, 2009). "In Art We Lust". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- Grimes, William (July 22, 2011). "Lucian Freud, Figurative Painter Who Redefined Portraiture, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times.

- Monaghan, Peter (January 2, 2011). "Unveiling the American Nude". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Riding, Alan (September 25, 1995). "The School of London, Mordantly Messy as Ever". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Schjeldahl, Peter (June 9, 2008). "Funhouse: A Jeff Koons retrospective". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

Web

[change | change source]- Department of Museum Education (March 18, 2003). "Body Language: How to Talk to Students about Nudity in Art" (PDF). Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Graves, Ellen (2003). "The Nude in Art – a Brief History". University of Dundee. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Hamilton, Julie (October 2, 2018). "Mona Kuhn Turns Flat Photos into an Immersive Environment". INDY Week. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- Legacy Staff (July 22, 2011). "Lucian Freud painted people "how they happen to be"".

- MOMA (2012). "Naked Before the Camera". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Postiglione, Corey. "The Postmodern Nude". Brad Cooper Gallery. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Rodgers, David; Plantzos, Dimitris (2003). Nude. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-188444605-4.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Ryder, Edmund C. (January 2008). "Nudity and Classical Themes in Byzantine Art". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- "Jenny Saville". Saatchi Gallery. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- Sorabella, Jean (January 2008a). "The Nude in Western Art and its Beginnings in Antiquity". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Sorabella, Jean (January 2008b). "The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Sorabella, Jean (January 2008c). "The Nude in Baroque and Later Art". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Naked Portrait 1972-3". The Tate Modern. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "Edward Weston". Edward-Weston.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Michelangelo Gallery". Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Alan F. Dixson; Barnaby J. Dixson (2011). "Venus Figurines of the European Paleolithic: Symbols of Fertility or Attractiveness?". Journal of Anthropology. 2011: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2011/569120.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Clark 1956.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nead 1992.

- ↑ Tomlinson & Calvo 2002.

- ↑ Lovejoy, Bess (2014-07-11). "Portrait of Ms Ruby May: Leena McCall's painting runs up against the pubic hair police". Slate.com. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ↑ Bernheimer 1989.

- ↑ "Ariadne Asleep On The Island Of Naxos". New-York Historical Society. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ↑ Eck 2001.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dijkstra 2010.

- ↑ Steiner 2001.

- ↑ "Body Language: How to Talk to Students about Nudity in Art" (PDF). Art Institute of Chicago. March 18, 2003. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Borzello 2012.

- ↑ Graves 2003.

- ↑ Sorabella 2008a.