User:MdWikiBot/Diazepam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /daɪˈæzɪpæm/ |

| Trade names | Valium, Vazepam, Valtoco, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682047 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | High[1] |

| Addiction liability | Moderate[2][3] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, IM, IV, rectal, nasal spray[4] |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 76% (64–97%) by mouth, 81% (62–98%) rectal[6] |

| Metabolism | Liver—CYP2B6 (minor route) to desmethyldiazepam, CYP2C19 (major route) to inactive metabolites, CYP3A4 (major route) to desmethyldiazepam |

| Elimination half-life | (50 hours); 20–100 hours (36–200 hours for main active metabolite desmethyldiazepam)[7][5] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Chemical and physical data | |

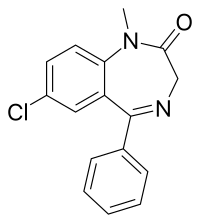

| Formula | C16H13ClN2O |

| Molar mass | 284.74 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Diazepam, first marketed as Valium, is a medicine of the benzodiazepine family that typically produces a calming effect.[9] It is commonly used to treat a range of conditions, including anxiety, seizures, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, muscle spasms, trouble sleeping, and restless legs syndrome.[9] It may also be used to cause memory loss during certain medical procedures.[10][11] It can be taken by mouth, inserted into the rectum, injected into muscle, injected into a vein or used as a nasal spray.[4][11] When given into a vein, effects begin in one to five minutes and last up to an hour.[11] By mouth, effects begin after 15 to 60 minutes.[12]

Common side effects include sleepiness and trouble with coordination.[11][7] Serious side effects are rare.[9] They include suicide, decreased breathing, and an increased risk of seizures if used too frequently in those with epilepsy.[9][11][13] Occasionally, excitement or agitation may occur.[14][15] Long term use can result in tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms on dose reduction.[9] Abrupt stopping after long-term use can be potentially dangerous.[9] After stopping, cognitive problems may persist for six months or longer.[14] It is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[11] Its mechanism of action is by increasing the effect of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[14]

Diazepam was patented in 1959 by Hoffmann-La Roche.[9][16][17] It has been one of the most frequently prescribed medications in the world since its launch in 1963.[9] In the United States it was the highest selling medication between 1968 and 1982, selling more than two billion tablets in 1978 alone.[9] In 2017, it was the 135th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than five million prescriptions.[18][19] In 1985 the patent ended, and there are now more than 500 brands available on the market.[9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to lorazepam.[20] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.01 per dose as of 2015[update].[21] In the United States, it is about US$0.40 per dose.[11]

References

[change | change source]- ↑ Edmunds, Marilyn; Mayhew, Maren (17 April 2013). Pharmacology for the Primary Care Provider (4th ed.). Mosby. p. 545. ISBN 9780323087902. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Clinical Addiction Psychiatry. Cambridge University Press. 2010. p. 156. ISBN 9781139491693. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Ries, Richard K. (2009). Principles of addiction medicine (4 ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 106. ISBN 9780781774772. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Valtoco- diazepam spray". DailyMed. 13 January 2020. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Diazepam Tablets BP 10mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 16 September 2019. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ↑ Dhillon S, Oxley J, Richens A (March 1982). "Bioavailability of diazepam after intravenous, oral and rectal administration in adult epileptic patients". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 13 (3): 427–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01397.x. PMC 1402110. PMID 7059446.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Valium- diazepam tablet". DailyMed. 8 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ↑ "Interpreting Urine Drug Tests (UDT)". Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 Calcaterra NE, Barrow JC (April 2014). "Classics in chemical neuroscience: diazepam (valium)". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 5 (4): 253–60. doi:10.1021/cn5000056. PMC 3990949. PMID 24552479.

- ↑ "Diazepam". PubChem. National Institute of Health: National Library of Medicine. 2006. Archived from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2006-03-11.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 "Diazepam". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- ↑ Dhaliwal JS, Saadabadi A (2019). "Diazepam". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725707. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- ↑ Dodds TJ (March 2017). "Prescribed Benzodiazepines and Suicide Risk: A Review of the Literature". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 19 (2). doi:10.4088/PCC.16r02037. PMID 28257172.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Riss J, Cloyd J, Gates J, Collins S (August 2008). "Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 118 (2): 69–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01004.x. PMID 18384456.

- ↑ Perkin, Ronald M. (2008). Pediatric hospital medicine : textbook of inpatient management (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 862. ISBN 9780781770323. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 535. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ US patent 3371085, Leo Henryk Sternbach & Earl Reeder, "5-ARYL-3H-1,4-BENZODIAZEPIN-2(1H)-ONES", published 1968-02-27, issued 1968-02-27, assigned to Hoffmann La Roche AG

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ "Diazepam - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Diazepam". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2015.